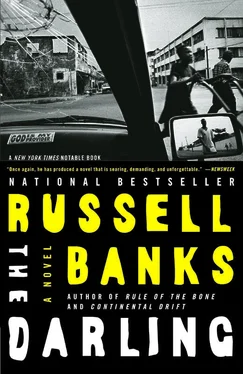

Russell Banks - The Darling

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Russell Banks - The Darling» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2005, Издательство: Harper Perennial, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Darling

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harper Perennial

- Жанр:

- Год:2005

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Darling: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Darling»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is the story of Hannah Musgrave, a political radical and member of the Weather Underground.

Hannah flees America for West Africa, where she and her Liberian husband become friends of the notorious warlord and ex-president, Charles Taylor. Hannah's encounter with Taylor ultimately triggers a series of events whose momentum catches Hannah's family in its grip and forces her to make a heartrending choice.

The Darling — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Darling», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

With his back to me, Dillon asked “Will you come back someday?”

“Someday? Of course! And it won’t be someday. It’ll be soon, as soon as possible.”

“Okay, then. Go ahead,” he said. He slipped out of his bed and in tee shirt and shorts, barefoot, headed for the door, and was gone. The twins watched him leave and began to get out of their beds to follow.

I said, “What about you two? Is it all right with you, that I have to go away for a while?”

They stopped by the door and turned back and smiled sweetly, both of them, as if they’d already discussed the subject and had reached an easy agreement. Paul said, “Yes, Mammi. It’s all right. You can go.” Both twins waved goodbye to me, and ran to catch up to their brother.

When you part with someone you love, there’s usually an aura of grief attached. But saying goodbye has never been difficult for me. I do it quickly and with little felt emotion, until afterwards, when I’m by myself and it’s done and it’s too late for any feelings that might slow or clog my departure. I sat at the foot of my eldest son’s rumpled, empty bed alongside the two empty beds of his brothers and saw that for the first time in nearly eight years I was alone again. And for the first time since the day I went underground, I felt strong and free.

The room slowly filled with hazy gray morning light, gradually bringing into sharp focus the clutter of the boys’ toys and clothing, all the defining props and evidence of their ongoing existence. Though I had been the one to clip and tape the pictures, maps, and drawings to the walls, the boys had chosen them. And though I had purchased most of their possessions, it was with money given me by their father. To my eyes, there was nothing of mine in that room, no evidence that I existed.

MY LEAVE-TAKING from Liberia in 1983 went nearly as unremarked as my arrival had back in 1975. I packed my old duffel and said my goodbyes quickly and easily, as if flying to Freetown or Dakar for a holiday weekend with friends. The boys, naturally, were afraid they were being abandoned by their mother, but they could not admit it, even to one another.

The night before I left, Sam Clement dropped by the house on his way home from the embassy, to wish me bon voyage, he said, and to reassure me that he’d keep an eye on my boys, including Woodrow (wink wink), until I got back, when in fact he was merely making sure that I knew that my departure from the country was under the protection and in the interests of official U.S. policy towards Liberia and the administration of President Doe.

Later, the president himself telephoned to say that he hoped I had a “superb” holiday in America and used the word superb , his new word of the week, I guessed, twice more, in reference to my sons and to characterize my company, which he said would be very much missed during the upcoming national holiday. As an expression of his personal affection for me, he was providing Woodrow with a bit of a cash bonus to help pay my travel expenses and would send it to me via Woodrow’s trusty assistant, Satterthwaite.

Woodrow, who left early for the ministry the next morning and did not see me off later, was clearly relieved to have me gone from his household — it was saving his life, after all — but had to say that he would miss me terribly. Then Satterthwaite arrived with the car around three that afternoon and handed me the packet given to him at the office by Woodrow. It contained my one-way ticket to JFK and an envelope with fifty crisp, one-hundred-dollar bills inside. Satterthwaite looked at the ground and said to me, “I hope you come back soon-soon, Miz Sundiata,” but I knew he was thinking, Damn good t’ing dis bitch finally outa here, ’cause someday her gonna get mad at de ol’ man an’ tell ’im what we done once way back den an’ mek de ol’ man fire me or wuss .

Jeannine stood woefully at the front gate as Satterthwaite drove me from the yard, tears running down her round, brown face, her fingers crossed in a behind-the-back hex designed to keep me from ever coming back, making the house hers, my children hers, my husband and his wealth and power hers.

No one else took account of my departure from Liberia that day. It happened so quickly, of course, that there was little occasion for a farewell party or visits with the half-dozen or so people in Monrovia whom I counted as friends. And they weren’t really friends, anyhow — merely acquaintances, the wives of Woodrow’s colleagues and business associates. Elizabeth and Benji, who had been running the lab on their own for the last seven years, were not my friends, though I knew them well and had seen them nearly every day on my visits with my dreamers. The university had not bothered to replace me after I left my post as clerk of the works and had withdrawn all but minimal support for the project, providing only enough funding to keep the chimps caged and alive. This was before AIDS research had gotten under way in earnest, when a new reason would arise to infect the animals with disease and monitor their reactions. If they’d been allowed to do it, the university officials would have had the animals put down, cheaper than releasing them to the wild and easier on the animals, most of whom had been traumatized by capture and confinement and had gone through a simian version of the Stockholm syndrome and had so thoroughly substituted their captors’ desires for their own that they were incapable of living naturally in the wild.

Early the morning of the day I left Monrovia, even before packing my bag, I went out to the lab, ostensibly to say goodbye to Elizabeth and Benji, but actually it was for a final visit with the chimps, for, without my ongoing vigilance, I did not think they would live long under their keepers’ care. The machinery that paid Elizabeth and Benji their monthly salaries was permanently in place, it seemed, and did not depend on there being any chimpanzees in those cages. Corruption thrives on process, not product, so it didn’t matter to them or anyone else if the chimps starved or sickened and died, if the cages one by one were emptied out, because Elizabeth and Benji would still be paid by the American university for maintaining its research facility and animal subjects in Liberia, and the university would still be paid by the multinational pharmaceutical company based in New Jersey, and the pharmaceutical company, through tax write-offs and federal grants, would still be paid by the American citizenry. Though I had come dangerously close to loving the product, the dreamers caged in a Quonset hut out at the edge of the city, I was merely a witness to the process, helpless to change it at any level.

I rode out on my bicycle, as had long been my habit, and as usual no one was at the lab. Elizabeth’s and Benji’s routines had long since been reduced to showing up twice a day for only as long as it took to feed the chimps and hose down the floor of the Quonset hut and conduct whatever little side business the two ran out of the all-but-defunct lab. They had sold off piecemeal most of the office furniture and the household goods and furnishings from the three cottages — after taking as much of it as they wanted for their own use — and were renting out the cottages on an hourly basis, I suspected, for I had on several occasions seen strangers, men with women, arriving and leaving at odd and unlikely hours. I never entered the cottages to see for myself who was living or working there — prostitutes, I assumed — and never confronted or quizzed Elizabeth or Benji about the use they were making of the compound.

They could strip it bare, for all I cared, or trash it or turn a profit from it any way they wanted. I had no loyalty to the university that financed the project and did not believe in the purposes for which the facility had been established in the first place. To me, it was a prison whose inmates had been deranged first by the circumstances of their capture and then by their lifelong confinement, inmates rendered incapable of functioning outside their cells, kept there now solely for their own safety. I made sure that they were properly fed and watered twice a day — either by Elizabeth and Benji or, if they didn’t show up, by me — and that their cages were washed down, and when on occasion one of the chimps injured itself or fell ill, I nursed it back to health, and, as happened several times over the years, if one of them died from an undiagnosed illness or simply from sadness, I buried the poor creature out behind the Quonset hut and erected a wooden marker with the dreamer’s name painted on it, Hooter and Livingston and Marcie . And grieved.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Darling»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Darling» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Darling» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.