William Gerhardie - The Polyglots

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Gerhardie - The Polyglots» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, Издательство: Melville House, Жанр: Классическая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Polyglots

- Автор:

- Издательство:Melville House

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Polyglots: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Polyglots»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Polyglots — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Polyglots», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

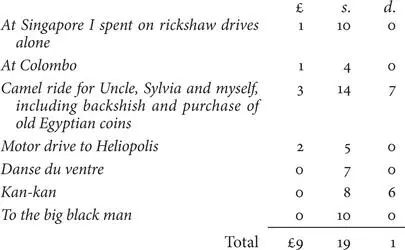

Reason for yourself. Yesterday again Captain Negodyaev borrowed money. As usual we spoke of religion and the hereafter; he listened amiably, only to ask me at the end of it to lend him £7. Of course he assured me that he would pay me back the money. The sincerity of his intention, in the face of the clean impossibility of his ever doing so, is formidable indeed, and does him credit. But Russians never pay their debts; they don’t consider it good fellowship. Aunt Molly had drawn to date the sum of £14 12s. Uncle Emmanuel this morning asked me for £2. Captain Negodyaev’s debt was £19. Berthe had had £4. Sylvia £30. A total of £69 12s.

Grand Total: Seventy-nine pounds eleven shillings and a penny.

‘Hell! Hell! Perfect hell!’

‘What is it, darling?’

‘Oh, not you.’

‘Alexander — please give me £15. Do you mind?’

‘I don’t mind. But where am I to take it? Honestly and truly— where? Unless I really go and borrow some!’

‘Yes, borrow some.’ My grandfather rose in the grave.

So far Aunt Teresa had not drawn on me. But I knew she had almost exhausted the advance from Gustave’s bank.

‘What shall we do,’ she asked, ‘when we have no more money?’

‘Of course, there is the International Red Cross.’

She meditated. ‘I hardly think—’ she said. There was a pause.

‘Can’t you, George, do something?’

‘I can.’

‘What?’

‘I have begun a novel. I have already written the title-page.’

My aunt looked at me with that strange look an English public school boy may cast upon a boy he secretly respects for being ‘clever’ but nevertheless regards as ‘queer’, and is a little sorry for him, for all that.

‘Is it going to sell well?’ she asked.

The exorbitant demands of my aristocratic aunt would tax the circulation of a best-seller. You will see the force of this my writing.

‘I hope you’ll make money,’ she said.

I was silent.

‘Anatole would have helped me if he were alive, I know. He was so generous.’ I was silent.

‘Is there a lot of action in it? People nowadays want something with lots of action and suspense.’

‘Oh, lots and lots!’ I answered savagely. ‘Gun play in every chapter. Fireworks! People chasing each other round and round and round till they drop from exhaustion.’

Aunt Teresa looked at me uncertainly, not knowing whether I was serious or laughing, and if laughing whether I was laughing at herself. ‘I wonder,’ she said, ‘whom you could write about?’

‘Well, ma tante , you seem to me a fruitful subject.’

‘H’m. C’est curieux . But you don’t know me. You don’t know human nature. What could you write about me?’

‘A comedy.’

‘Under what title?’

‘Well, perhaps— À tout venant je crache !’

‘You want to laugh at me then?’

‘No, that is not humour. Humour is when I laugh at you and laugh at myself in the doing (for laughing at you), and laugh at myself for laughing at myself, and thus to the tenth degree. It’s unbiased, free like a bird. The inestimable advantage of comedy over any other literary method of depicting life is that here you rise superior, unobtrusively, to every notion, attitude, and situation so depicted. We laugh — we laugh because we cannot be destroyed, because we do not recognize our destiny in any one achievement, because we are immortal, because there is not this or that world; but endless worlds: eternally we pass from one into another. In this lies the hilarity, futility, the insurmountable greatness of all life.’ I felt jolly, having gained my balance with one coup . And suddenly I thought of Uncle Lucy’s death; and I realized it was in line with the general hilarity of things!

‘I suppose,’ she said, ‘we shall have to put up at an hotel in London.’

I sighed.

‘To live at a London hotel is like living in a taxicab with the taximeter leaping all the time—2s. 6d. — 3s. 3d. — 4s. 9d. — while you breathe. It’s awful.’

There was a pause.

‘The book,’ said my aunt.

‘The book,’ said my uncle.

The sea had calmed down a little, the surges rolled more steadily and more sensibly, as if ashamed of their drunken excesses of the night before.

‘It seems to me I have a soul for music, that possibly I had better chuck the book and start on a sonata, but the thought of crochets, quavers, demi-semi-quavers and what not, necessitates my keeping all my musical emotion to myself.’

‘There is no money in music,’ she said coldly.

‘Or I may conceivably become a psycho-analyst, an architect, a boxer, or a furniture-designer.’

‘No, no,’ she said. ‘The book. The book.’

‘The book,’ said my uncle.

Well, writing has its compensations. For if you cannot put the fire into your manuscript, you can always put your manuscript into the fire. You have written one novel, and you are writing another. Your own particular publisher writes to you at intervals: ‘How goes it? How is the spirit moving you?’ And you reply, with the expression of a hen hatching a rare egg: ‘I think it is all right … I think it is coming out all right. I think we are saved.’ And he retires on tiptoe, frightened, frightened lest he frighten you off this precious gold egg. And then he comes again: ‘How goes it? Nearly ready?’

‘Not yet.’

And he goes and buys the paper and the cardboard and the necessary implements in anticipation of your work which is now ‘in preparation’.

Writing has its compensations. The misguided reviewers who have damned my last book, and who will damn this one, I damn in advance. My last one was a macédoine of vegetables. The critics — big dogs, small dogs, hounds and pekingese, came up and sniffed at an unfamiliar vegetable dish, and went away, wagging their tails confusedly. But this should be more beefy. Shall I write it as a moral story with a lesson: pointing out what happens when a selfish aunt is allowed to have it all her own evil way? Or shall I—? No matter. I am not — you won’t misunderstand me — writing a novel: I am asking: will this do for a novel?

Suddenly I was seized with energy, filled with dread lest I should lose another moment. After all these months of indolence I suddenly conceived that I was in a hurry. It was as if these wasted months had tumbled over me and were pressing me down with their weight. I longed to see it finished, printed, an accomplished task embodied in between two cardboard sheets of binding, wrapped in a striking yellow jacket, and sold at so much net. This old decrepit ship was so intolerably slow. She literally went to sleep. I wanted to do things, to live, to work, to build, to shout. To promote companies, conduct a symphony orchestra, organize open-air meetings, paint pictures, preach sermons, act Hamlet, work in a coal mine, write to the Press. And then Sylvia comes and tells me that my aunt is again as sick as a cat. Gustave — the lucky dog. How I envied him, and how stupid it was that at this very moment, perhaps, he might be envying me.

Bah!

I am mortally sick of them, of immoral old uncles, insatiable women, Belgian duds, impecunious captains, insane generals, stink -making majors, pyramidon-taking aunts! Of aspirin, tisane , eau-de-Cologne. Of the scent of powder, of Mon Boudoir aroma. And when Sylvia steals at night into my cabin and talks of divorce in order that we may consolidate our union, I visualize the camisole and knickers, my head goes round from her scent Cœur de Jeanette , and though I still feel she is very beautiful I say ‘What of it?’ and my thoughts go out to my unfortunate Uncle Lucy with a dawning understanding.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Polyglots»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Polyglots» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Polyglots» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.