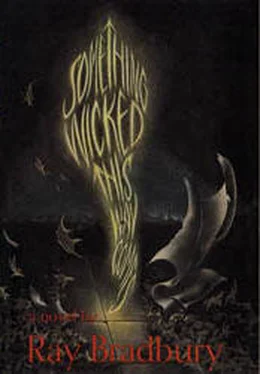

Something Wicked This Way Comes

WITH GRATITUDE TO JENET JOHNSON

who taught me how to write the short story

AND TO SNOW LONGLEY HOUSH

who taught me poetry at Los Angeles High School a long time ago

AND TO JACKGUSS

who helped with this novel not so long ago

Man is in love, and loves what vanishes.

W.B. YEATS

They sleep not, except they have done mischief;

And their sleep is taken away,

unless they cause some to fall

For they eat the bread of wickedness,

And they drink the wine of violence.

PROVERBS 4: 16—17

I know not all that may be coming, but be it what it will, I’ll go to it laughing.

STUBB in Moby Dick

First of all, it was October, a rare month for boys. Not that all months aren’t rare. But there be bad abd good, as the pirates say. Take September, a bad month: schoool begins. Consider August, a good month: school hasn’t begun yet. July, well, July’s really fine: there’s no chance in the world for school. June, no doubting it, June’s best of all, for the school doors spring wide and September’s a billion years away.

But you take October, now. School’s been on a month and you’re riding easier in the reins, jogging along. You got time to think of the garbage you’ll dump on old man Prickett’s porch, or the hairy-ape costume you’ll wear to the YMCA the last night of the month. And if it’s around October twentieth and everything smoky-smelling and the sky orange and ash grey at twilight, it seems Hallowe’en will never come in a fall of broomsticks and a soft flap of bedsheets around corners.

But one strange wild dark long year, Hallowe’en came early.

One year Hallowe’en came on October 24, three hours after midnight.

At that time, James Nightshade of 97 Oak Street was thirteen years, eleven months, twenty-three days old. Next door, William Halloway was thirteen years, eleven months and twenty-four days old. Both touched toward fourteen; it almost trembled in their hands.

And that was the October week when they grew up overnight, and were never so young any more. . .

The seller of lightning-rods arrived just ahead of the storm. He came along the street of Green Town, Illinois, in the late cloudy October day, sneaking glances over his shoulder. Somewhere not so far back, vast lightnings stomped the earth. Somewhere, a storm like a great beast with terrible teeth could not be denied.

So the salesman jangled and clanged his huge leather kit in which oversized puzzles of ironmongery lay unseen but which his tongue conjured from door to door until he came at last to a lawn which was cut all wrong.

No, not the grass. The salesman lifted his gaze. But two boys, far up the gentle slope, lying on the grass. Of a like size and general shape, the boys sat carving twig whistles, talking of olden or future times, content with having left their fingerprints on every movable object in Green Town during summer past and their footprints on every open path between here and the lake and there and the river since school began.

‘Howdy, boys!’ called the man all dressed in storm-coloured clothes. ‘Folks home?’

The boys shook their heads.

‘Got any money, yourselves?’

The boys shook their heads.

‘Well—’ The salesman walked about three feet, stopped and hunched his shoulders. Suddenly he seemed aware of house windows or the cold sky staring at his neck. He turned slowly, sniffing the air. Wind rattled the empty trees. Sunlight, breaking through a small rift in the clouds, minted a last few oak leaves all gold. But the sun vanished, the coins were spent, the air blew grey; the salesman shook himself from the spell.

The salesman edged slowly up the lawn.

‘Boy,’ he said. ‘What’s your name?’

And the first boy, with hair as blond-white as milk thistle, shut up one eye, tilted his head, and looked at the salesman with a single eye as open, bright and clear as a drop of summer rain.

‘Will,’ he said. ‘William Halloway.’

The storm gentleman turned. ‘And you?’

The second boy did not move, but lay stomach down on the autumn grass, debating as if he might make up a name. His hair was wild, thick, and the glossy colour of waxed chestnuts. His eyes, fixed to some distant point within himself, were mint rock-crystal green. At last he put a blade of dry grass in his casual mouth.

‘Jim Nightshade,’ he said.

The storm salesman nodded as if he had known it all along.

‘Nightshade. That’s quite a name.’

‘And only fitting,’ said Will Halloway. ‘I was born one minute before midnight, October thirtieth, Jim was born one minute after midnight, which makes it October thirty-first.’

‘Hallowe’en,’ said Jim.

By their voices, the boys had told the tale all their lives, proud of their mothers, living house next to house, running for the hospital together, bringing sons into the world seconds apart; one light, one dark. There was a history of mutual celebration behind them. Each year Will lit the candles on a single cake at one minute to midnight. Jim, at one minute after, with the last day of the month begun, blew them out.

So much Will said, excitedly. So much Jim agreed to, silently. So much the salesman, running before the storm, but poised here uncertainly, heard looking from face to face.

‘Halloway. Nightshade. No money, you say?’

The man, grieved by his own conscientiousness, rummaged in his leather bag and seized forth an iron contraption.

‘Take this, free! Why? One of those houses will be struck by lightning! Without this rod, bang! Fire and ash, roast pork and cinders! Grab!’

The salesman released the rod. Jim did not move. But Will caught the iron and gasped.

‘Boy, it’s heavy! And funny-looking. Never seen a lightning-rod like this. Look, Jim!’

And Jim, at last, stretched like a cat, and turned his head. His green eyes got big and then very narrow.

The metal thing was hammered and shaped half-crescent, half-cross. Around the rim of the main rod little curlicues and doohingies had been soldered on, later. The entire surface of the rod was finely scratched and etched with strange languages, names that could tie the tongue or break the jaw, numerals that added to incomprehensible sums, pictographs of insect-animals all bristle, chaff, and claw.

‘That’s Egyptian.’ Jim pointed his nose at a bug soldered to the iron. ‘Scarab beetle.’

‘So it is, boy!’

Jim squinted. ‘And those there—Phoenician hen tracks,’

‘Right!’

‘Why?’ asked Jim.

‘Why?’ said the man. ‘Why the Egyptian, Arabic, Abyssinian, Choctaw? Well, what tongue does the wind talk? What nationality is a storm? What country do rains come from? What colour is lightning? Where does thunder go when it dies? Boys, you got to be ready in every dialect with every shape and form to hex the St Elmo’s fires, the balls of blue light that prowl the earth like sizzling cats. I got the only lightning-rods in the world that hear, feel, know, and sass back any storm, no matter what tongue, voice, or sign. No foreign thunder so loud this rod can’t soft-talk it!’

But Will was staring beyond the man now.

‘Which,’ he said. ‘Which house will it strike?’

‘Which? Hold on. Wait.’ The salesman searched deep in their faces. ‘Some folks draw lightning, suck it like cats suck babies’ breath. Some folks’ polarities are negative, some positive. Some glow in the dark. Some snuff out. You now, the two. . .I—’

‘What makes you so sure lightning will strike anywhere around here?’ said Jim suddenly, his eyes bright.

Читать дальше