After publication of his most successful novels, The Maltese Falcon, The Glass Key, and The Thin Man , when Black Mask couldn’t afford him any longer, Hammett turned again to the slick-paper market during his breaks from movie work. He published stories in Collier’s, Redbook , and Liberty — “On the Way,” which appeared in the March 1932 Harper’s Bazaar, is included here because it has not been collected previously — and he wrote others that were not placed, but his primary interest was the movies by that time. He was under contract to MGM, writing the original stories for their Thin Man series published in our Return of the Thin Man (2012).

To our minds, this volume includes some of Hammett’s finest short fiction, and there is strong evidence that he valued these stories. Hammett was not a hoarder. He disposed of books, magazines, and manuscripts as soon as he was done with them. But he saved the typescripts and working drafts of stories in this book for more than thirty years, moving from coast to coast, hotel to hotel, and among several apartments. They were important to him. While many of these stories were clearly prepared for submission, with a heading on the typescript giving Hammett’s address, the word count, and the rights offered, there are only two pieces of evidence that he actually sent any of them out. A sheet is attached to “Fragments of Justice” with a note in Hammett’s hand, “Sold to the Forum , but probably never published.” Forum magazine published three book reviews by Hammett between 1924 and 1927, but not “Fragments of Justice.” In a letter to his wife, Jose, Hammett remarks that one story sent to Blue Book in 1927 “came sailing back”; the story he referred to is unidentified, but a good guess is “The Diamond Wager,” published in Detective Fiction Weekly in 1929 under the pseudonym Samuel Dashiell. Blue Book , distinguished at the time for their publication of Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot stories, was among the highest-paying detective-fiction pulps, the kind of market Hammett would have been trying in 1927, and “The Diamond Wager” seems tailor-made for them.

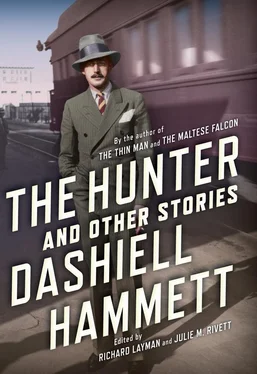

After publication of The Maltese Falcon established Hammett as one of the finest writers in America, he could easily place his fiction in most any market he chose, but before that he was typed as a genre writer, a hard tag to overcome. His primary readership was mystery fans interested in realistic fiction about crime. Before publication of The Maltese Falcon , a story submission to the slicks by Dashiell Hammett would have gone into the slush pile with hundreds — more likely thousands — of other submissions. It would have been a hard sell. With two exceptions, “The Hunter” and the light satire “The Sign of the Potent Pills,” the stories in this volume are not detective stories. They are Hammett’s attempts to resist and then to break out of the mold that came to define him as a writer.

After 1934, when The Thin Man was published and Hammett began devoting his full energies as a writer to screen stories, he stopped publishing his work. For the next twenty-seven years remaining in his life he published no new fiction. For the first sixteen years of the period, until 1950, he didn’t need the money and had other interests; for the last ten he seemed to lack the energy and the spirit to write. After Hammett died, in January 1961, his literary properties fell under the complete control of Lillian Hellman, who set about carefully and expertly reviving his literary reputation — as a detective-fiction writer. There is evidence that she began editing some of the stories in this volume for publication — her light edits appear on a couple of typescripts — but she restricted her efforts to republishing what she regarded as his best detective fiction, because that was where the market lay. Hellman sold Hammett’s literary remains — or most of them, one assumes — to the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas, from 1967 to 1975, and guarded access to the archive carefully. These stories were first discovered in the Ransom Center archive in the late 1970s, but publication was restricted. Over the last thirty-five years, Hammett’s unpublished stories have been regularly “rediscovered,” but for practical reasons, having to do primarily with licenses to publish and the indifference of the trustees who held sway until they were replaced at the end of the last century, these stories remained unpublished. Make no mistake: the stories in this book are not newly discovered; they are made newly available to a wide readership.

This book is arranged into four broadly defined sections — with a special appendix. Within each section stories are arranged into roughly chronological order, sometimes on the basis of guess and instinct, though the headings, paper, and typographical arrangement offer reliable clues in most cases. The texts are essentially as Hammett left them. We have resisted editing and modernizing his style: compound words, for example, are hyphenated as Hammett wrote them, and his old style of forming possessives is retained. In some cases punctuation has been judiciously standardized. In one instance an untitled story, which we call “The Cure,” has its title supplied, with the advice and consent of the people best positioned to judge what title Hammett might have chosen — his daughter and granddaughter.

The appendix deserves special attention. Provided courtesy of a generous private collector, it is the elegant beginning of a Sam Spade story or novel, perhaps. It alone among the several fragments Hammett left behind was chosen for inclusion in this print edition of The Hunter and Other Stories . Interesting though they may be, literary fragments are of primary interest to a limited audience. A selection of Hammett’s unfinished starts is included as a feature of the e-book edition of this collection.

R. L.

The four stories in this section provide a prismatic view of Hammett’s experiments over a decade with the treatment of crime. These stories show Hammett trying different forms — from a standard Black Mask — type story, to parody, to Golden Age models, to the type of hard modernism associated with Hemingway — and varying types of narration. Three of the stories are narrated in the third person, though each in a different variety, and the other is told in the first-person voice of a wily and affected dilettante with a keen interest in fine jewels, suggesting a more famous Hammett villain.

“The Hunter” is a detective story in the mold of the Black Mask Continental Op stories, but with an important difference. Here the detective, named Vitt, is as hard-boiled as a detective gets. He has a job to do, and he does it with neither distraction nor emotional involvement, and then he turns ironically to his own mundane domestic concerns at the end. Judging from the return address on Eddy Street, where Hammett lived from 1921 to 1926, it was likely written about 1924 or 1925, when Hammett wrote six stories published in magazines other than Black Mask and introduced two new protagonists in stories told in the third person, as “The Hunter” is — Steve Threefall in “Nightmare Town” ( Argosy All-Story Weekly , December 27, 1924) and Guy Tharp in “Ruffian’s Wife” ( Sunset , October 1925).

“The Sign of the Potent Pills” is a farce that builds on the depiction of the detective as something less than a heroic crime fighter. The return address is 891 Post Street, where Hammett lived from 1927 to 1929. In January 1926, Hammett published “The Nails in Mr. Cayterer,” a satirical story about a writer-detective named Robin Thin similar in tone to “The Sign of Potent Pills.” (Another Robin Thin story, “A Man Named Thin,” was published shortly after Hammett’s death in 1961.) In this typescript someone crossed out the first two paragraphs of the story. They have been restored here, because they provide the only mention of the billboard that gives the story its name and identify Pentner, who calls the police at the end. Lillian Hellman edited the story, and the first paragraphs seem to have been cut by her. Hellman’s edits have been accepted only when they corrected clear typographical errors or undeniable infelicities.

Читать дальше