‘I was close to death, out there, after you left. As close as a man can come.’

‘I was there as well. Afterwards, in the storm.’

‘I do not want to go to that place again. Or beyond it. I do not like what I saw there. Yet all men do. And I shall go there soon. The next winter will finish me soon enough. As it should have done three years ago. As it should have killed you.’

He looked back at me and there was a strange hunger in his eyes – a kind of needful madness.

‘Has it done the same to you?’ he said.

‘No,’ I said. ‘I am not afraid.’

The pain broke across his face, and shame as well. But he nodded, accepting.

‘Why did you not kill me? Why not spare me this shame?’

‘I knew it would slow the others. That they would not leave you. That was all. I would have killed you, if it were not for that.’ I hesitated. ‘What will you say to the others?’ I asked.

‘To Björn? And his kin? Perhaps I would speak of you to them, if ever they came here. But they do not. I will not speak of your return. I do not care who else dies in this feud. But you are a fool if you continue the killing.’

‘And a coward if I do not.’

‘And there is the trap. Our people came to this island to be free. Of kings, tyrants, men who would tell us what to do. Yet here we are. With less freedom than a slave.’

He picked up a stick and poked at the little fire.

‘Put this aside, Kjaran,’ he said. ‘I am not a wealthy man. But I will give you silver – twice the blood-price for Gunnar and his family. Enough to settle the feud honourably. You can go to some other part of Iceland and begin your life again. Or I will give you the name. What is it that you want?’

‘I must have the name.’

He waited for a time, his eyes fixed on mine. He gave me as much time as he could to change my mind.

I left the shieling and struck out across the dale. I did not go to the west, towards the sea and Ragnar, Kari and Sigrid. I went south, along the familiar path. And I broke the promise that I had made to myself, that I would never set eyes on the valley again.

I walked down through the mountain passage and at the first farm I came to on the other side I traded my last silver arm-ring – the one Thoris had gifted me – for a good horse. I rode until I was in sight of Borg, the mountains and the sea. It was time to turn east then, to travel along the path of exiles and outlaws.

I was afraid that I would not remember the way, but I need not have worried. Every point on that journey was marked in my memory. There was no shape of stone, no cliff face or river or curving line of earth that I did not remember.

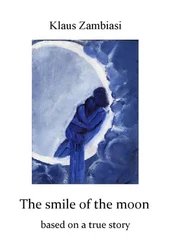

The passage was easier this time. It was the beginning of summer and the snow was gone from the lowlands. Yet still, I came to the heights and here the snow remained upon the ground, for it is a place that knows no summer.

The coward’s fear was building, every instinct I had warning me off that place. The horse beneath me felt my fear, in the way that beasts always do, wiser than men and cursed with silence. But as he danced and whickered beneath me, he reminded me to be brave. I touched my heels to his flanks and rode on.

It was before me once again. The valley where I had spent three years as an outlaw. A nameless place, for who would name a land where no man would wish to go to, where only the forgotten choose to live?

I could not see the herd of stolen sheep that should be wandering in the valley; perhaps Thorvaldur and Thoris had not gone raiding this early in the year. I tethered my horse at the bottom of the valley and it called out to me as I left it there. For he, too, could feel that this was a place where nothing should live and nothing could grow; the horse was afraid of being left there alone.

I began the slow climb up the side of the hill, pushing through snow slush and bog. I made my way towards the cave and I was afraid of what I would find there.

Perhaps they would cut me down: I was a free man and they still outlaws. But I had nowhere else to turn. And so I made my way up that hill and I remembered every step of the path, each little trap of earth and stone that waited to break my ankle, shatter my knee, leave me dying on the ground. Even the earth itself seems to long for the killing in such a place.

I smelt the cave before I saw it: the hot stink of close living that I had grown unaccustomed to. And I saw the shallow slit, in the side of the hill, above where some god or dragon slept. I let my hand drift to the knife at my hip as I drew close.

It was empty. I waited to see if some outlaw would stir from the blankets and filth, like a cursed man rising from a grave, but there was no one. I knelt beside the entrance, running my hand through the ash of a recent fire, the gnawed bones in a land where there were no flesh-eaters but men. In the air, the fresh stink of men in confinement. They had been here so I sat to wait, sitting atop that familiar warm stone at the back of the cavern where, deep below, a dragon still slumbered in the heart of the mountain.

*

I remembered lying in that cave, rotten with fever, my left hand dead to the touch. I remembered Thoris nursing me as he might have nursed a child. I remembered the coming of the Christian, the slow breaking of our friendship. I remembered swearing that I would never return to this place – another promise unkept. Then I heard the breaking of snow and there was no more time for memory.

A shadow at the entrance, the low sun at his back. I could not tell who it was at first. Once I would have known those men apart by smell alone, but I had lost that gift.

‘Welcome, Kjaran.’ It was the voice of the Christian that spoke.

‘Thorvaldur,’ I said.

A pause. ‘I do not know that I am glad to see you again.’

‘Where is Thoris?’

Thorvaldur made no reply at first. He slung his burden from his back: a skin full of water, fresh from the frozen river. He offered it to me first, as was my right as his guest. I let my hand wander from my knife to the water, but when I drank it it was sharp and piercing against my tongue. I winced, for I had grown unused to such things, and handed it back to the Christian. He chuckled a little and drank slowly, unmoved by the cold.

‘Thoris died, in this past winter.’

‘Did you kill him?’ I said, speaking softly.

He laughed again. ‘No, no. A fever took him. Quick and true.’ He leaned forward and put his hands together. ‘And now tell me, what brings you back here?’

I did not answer.

‘You longed to see us once again? I had not thought that of you. Or have you earned outlawry once more through some rash action?’ He rapped the fingers of one hand on the pommel of his sword. ‘Or have you come to claim some reward, for the killing of an outlaw? I did not think you fool enough to come alone, if that be your intention.’

‘You said that when we met again I could choose. Between your God and a death in battle.’

‘That I did. Are you ready to choose?’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘I wish to choose both.’

He stared at me for a moment, his eyes hunting across my face. Perhaps he thought I mocked him, an insult that he would answer with blood. But when he saw that I meant what I said he crowed with laughter, eyes rolling like a berserker, clapping his hands against his thighs in delight.

‘Oh, Kjaran,’ he said, ‘you do not know how long I have hoped to hear an answer such as that. The true answer. I have asked many that question, and none have spoken as you have.’ He cocked his head to the side. ‘Why do this?’

‘There are men I must fight. Too many for me to face alone. Will you stand beside me? Will you fight and die with me against them, if I swear to your God?’

Читать дальше