Lucius said, “Tomorrow, at the hospital, they’ll take care of you.”

The man said, “Nothing comes out.”

Lucius said, “I understand. Tomorrow, we will reach the hospital…”

“Nothing!”

“I understand. I…” He took a deep breath. “When did you last go?”

But the hussar didn’t answer. Instead, he turned, holding his penis in his open palm, as if to say to Lucius, Look . Lucius hesitated. Then, lighting a candle from his rucksack, he crouched before the hussar. Think. Remember the lectures on the anatomy of the bladder. Except he’d skipped them to work in Zimmer’s lab.

He told the man to bear down, and a single drop of urine appeared at the tip of his penis. Gently, Lucius palpated the man’s belly. It was tense, his bladder full. Once, chronic venereal disease was the kind of problem he might have joked about with Feuermann, hardly the glorious surgery he’d expected on the front. But now the possible consequences of an untreated obstruction ran through his mind. Did the bladder actually rupture? Or the urethra? Or did the kidneys shut down before anything tore?

“Tomorrow at the hospital…,” Lucius began.

The man shook his head. “I can’t get back on the horse.” He bent over, pushing his fist so hard into his belly that Lucius was now certain something would burst.

Leaving me alone with a dying horseman in an abandoned village, he thought. He didn’t know where he was going, nor how to return to Nagybocskó.

The soldier said, “Every month, I go… they use a little rod…”

“I know,” said Lucius. “It is called a bougie . But I don’t have one.”

The two men looked around the room, eyes passing over the saint’s icon, the music box. Then the hussar said, “For my rifle, there is a rod assembly…”

Lucius felt his stomach turn. “I can’t. They use petroleum jelly… For the rod to advance, we need…”

But the man was rummaging through his saddlebags, returning with a three-piece collapsible brush, with one piece screwing into the other. It looked like a medieval torture implement. But the pieces without bristles were thin and smooth, and even tapered at their threaded ends. From the bag, the man removed a tube of gun oil.

Lucius had two ampoules of morphine left, and he gave the hussar one, using the needle still dirty with his own blood. He told the man to lie down, and waited until the morphine took effect. Then he squeezed rifle oil onto the rod. Again he tried to recall what he’d read in the textbook. If he remembered correctly, the urethral canal took a sharp turn at the urethral sphincter. If he pushed too far, he could pierce through the wall of the canal. But if the stricture were closer, he might stand a chance. He took a deep breath. “Grab here,” he said, and had the hussar pull his penis straight. He placed the rod at the urethral opening and advanced it slowly in. The man tensed. Lucius stopped, now remembering that one of the risks of the procedure was opening a false passage. His left hand was trembling, and he braced it with his right. He found himself recalling how in Kraków, in the mess hall, he’d heard a pair of sappers talking about a certain kind of shaking that beset them as they gently wound the wires of their bombs. He advanced the rod farther, and then it reached resistance. He backed up, slipped it forward, again felt it stop. Then, with a push, past. Then the hussar roared, twisted away, leaving Lucius rod in hand, stumbling back, piss-sprayed as the man shattered a wall plank with his fist.

He’ll kill me, Lucius thought. But then the hussar began to laugh.

The next morning he was in tremendous spirits.

He sang as he urinated in many directions. “Orvos!” he said, embracing Lucius as he half-spoke, half-sang something in Hungarian, none of which Lucius understood. Save orvos. Doctor . It was enough.

They set out. Their trail joined with a rutted, empty road that climbed steeply into the hills. Now the hussar seemed positively garrulous. He sang and whistled and drummed on his thighs. It was good that Lucius was a doctor, he told him. Lots of patients. He made a sawing motion with his hand.

They stopped only for Lucius to inject more anesthetic into his wrist. By then the signs of war were gone, the forest clear. The only person they saw was an old man in the middle of a dark wood, rummaging through the snow. When the hussar slowed, Lucius was afraid that he would rob him just as he had robbed the others, but he only asked the way, and the old man pointed with a turnip as he leaned unsteadily on his stick.

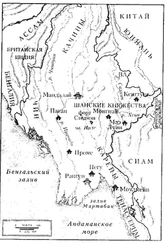

Dusk was falling when they came over a low hill and at last found themselves before a village. It was tucked in a softly sloping valley, with two streets of houses descending from a single wooden church of rough-hewn logs. Above the church, the road kept rising. Below, the valley widened into snow-covered fields that flanked a frozen river. “Lemnowice,” said the hussar. They followed the road down to the fields and then up past the houses. They were low-ceilinged huts, made of wood, straw-thatched, with tiny windows, all covered with wooden shutters so that it was impossible to see inside. There were no chimneys. A pair of drays lay in the road, seemingly abandoned, half-buried in snow. There was a flutter over one of the rooftops, and a huge black crow took off into the sky.

There was not a soul in sight. He saw no garrison, no sign of the army at all, certainly nothing that could be a hospital. Perhaps it lay beyond the hill, he thought. Unless, this, too, had been a mistake. Unless, after such a journey, he would have to turn around.

The hussar stopped before the church, motioning Lucius to descend. He obeyed, approached the door, and knocked. He waited. There was a narrow window in the door that reminded him of a castle arrow slit. The hussar told him to knock harder, and only then did he hear movement, the sound of footsteps. In the window, an eye appeared.

“Krzelewski,” said Lucius. “Medical lieutenant. Fourteenth Regiment, Third Army.”

Then a key in the lock, a clang of the mechanism. The door opened to reveal a nursing sister. She wore a stiff grey habit, and in one hand held a Mannlicher rifle, standard issue of the k.u.k .

“May I speak to the supervising physician?” he asked in German.

When she didn’t answer, he tried Polish.

“The doctor?” she replied, still staying back, in the shadows. “Didn’t you just say you’re him?”

The nurse’s name was Margarete. She gave no surname. It was not the custom of the Sisters of Saint Catherine to do so, she would explain. Even Margarete was a name she had assumed with her vows, abandoning her earthly appellation to the life she led before. Her face floated in the darkness of the narthex, and it was only when Lucius turned to see the hussar kick his horse and ride away ( flee, thought Lucius later) that she opened the door more widely, motioning for him to step inside with a sweeping of the gun. Then she threw her shoulder against the door. He stood in total darkness while she secured it, first turning the iron lock, then heaving a crossbar into the cleats. Turning to follow her movement, he heard a key slip into a second door, then the sonorous clanging of the mechanism as it engaged. Then, weapon swinging in her hand, she led him into the dim light of the nave.

As Lucius’s habit upon entering a house of God was to look up at the majesty of the ceiling, his first impression was that the church of Lemnowice was much like any other of the dozens of wooden churches he had visited in the Tatras, farther west, though this, with its heavy dome and tiny windows, suggested more an Eastern rite. A row of six wooden columns supported the ceiling, from which a pair of chains dangled, now empty of their chandeliers. In the distance, the north transept was illuminated by a lantern. The rest of the church was dark.

Читать дальше