In the morning, he removed the splint and let his hand hang free. Only once did he have to lift it, to salute the officer who took his papers at the station. When the train began to move, he splinted it again.

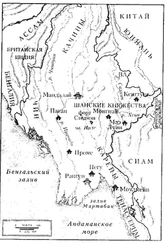

He reached Nagybocskó in the late afternoon, where the hussar escort was waiting.

* * *

From the little station house, they followed the road through snowy fields, before it entered a valley thick with pine. Milky layers of ice glinted on the branches, which clattered as the wind came through. Teardrops froze in the corners of Lucius’s eyes and on his lashes, and the shawl that wrapped his face grew thick with rime. Binding his reins about his good hand, he tried to brace his broken wrist, but the narrow road was hard as metal, and the horses slipped from time to time. When at last the pain grew unbearable, he called out for the hussar to stop.

He fumbled with his rucksack until he found the ampoules of cocaine and morphine. They had frozen, so he slipped them into his mouth to warm them. He injected the cocaine directly into his fracture, then paused, ready to inject the morphine, but stopped. No. Best to be sparing; he didn’t know how far they had to go.

The land rose, the valley steep but broad. Soon they reached a wooded pass. The road descended, crossed into another valley, and began to descend again. They passed the entrance to a village, marked by a painted sign with a primitive death’s-head and the words FLECKFIEBER!!!— typhus —and BEWARE SOLDIER! DO NOT ENTER HERE! DEATH AWAITS!!! in German, Polish, and what he assumed to be the same in Romanian, Ruthenian, and Hungarian.

The hussar crossed himself, and though they were far from the village entrance, he gave it a wide berth. As if something fanged and taloned might burst out and chase them down.

Lucius’s arm began to throb again. Again he called to the hussar to stop, uncapped the old needle, broke the morphine ampoule, and injected it into his arm.

The forest thinned. They passed empty fields, now scarred by war. Bomb craters, abandoned bulwarks, trenches. From a tree, something was hanging: a body, now encased almost entirely in ice. At the far end of the field lay a dark pile of what seemed like boulders, but as he drew closer, Lucius saw that they were frozen horses. There were perhaps fifty, half-covered in snow. Garish, dark-red flowers bloomed from their heads. In the shadows of the forest, he thought he saw others. The hussar slowed.

A scrap of livery fluttered lightly from one of the exposed saddles, the letters k.u.k. still visible.

Kaiserlich und königlich . Imperial and Royal. His army. Suddenly Lucius was afraid.

“Cossacks?”

Shadows danced deep in the woods. He saw the horsemen, creatures of so many childhood dreams. Then nothing but the trees.

“Cossacks don’t execute horses,” said the hussar, disdainfully, from behind his mask. “This is Austria in retreat.”

At first Lucius didn’t understand. But he was embarrassed to show his ignorance, and it was only as they rode on that he recalled the stories of surrender, the animals shot to keep them out of enemy hands.

It was close to dusk when they passed their first set of travelers, a refugee family leading a goat cart down the snowy road. There were four children, two on the cart, two walking, their faces swaddled like mummies, jackets stuffed with straw until they were nearly bursting at their seams.

In Hungarian, the hussar commanded them to stop. He pointed to the cart and spoke. The woman protested. Lucius couldn’t understand the words, but it was clear what she was saying: nothing here, some old rags—that’s all. The hussar dismounted from his horse and walked, somewhat stiffly, over to the cart, where he began to search. The woman followed him. “Nincs semmink!” she cried, both hands in prayer. “Nincs semmink! Nincs semmink!” But by then the hussar had found what she was hiding. One by one, he drew them out: rabbits, twitching, eyes wide, breath steaming, kicking their long back legs against the air.

Cries rose from the swaddled faces of the children. The hussar offered Lucius a rabbit, holding out the steaming creature in his extended hand, like a priest before a sacrifice. Lucius shook his head, but the hussar threw it to him anyway, and he caught it with his good arm, against his chest. Then he hesitated. He wanted to return it to the family, but he could feel the hussar watching him through the thin slits in his leather mask.

The rabbit kicked as he slipped it inside his greatcoat. It wriggled out. He caught it by its leg and this time tucked it inside his shirt, against his skin, where, out of terror or from some physiological change provoked by the change in temperature, it released a stream that trickled down his belly and his legs. Lucius could feel its heart thrumming against his skin. He did not understand why the hussar hadn’t killed the rabbits there, but this choice, before the children, seemed almost kind.

He kept his eyes from the family as they rode on.

They returned to the road. After another hour, the hussar stopped and dismounted slowly, even more stiffly than when he’d stopped before. He fumbled with his trousers as if to urinate, and Lucius turned to give him privacy. But when the man didn’t move for several minutes, Lucius looked back. Now something seemed wrong. Another minute, and Lucius heard him curse, then groan as if straining, before he gave up and climbed back on his horse.

Close to evening, they entered an empty village, stopping to billet in an abandoned house. The walls were bare; the kitchen was empty, the cabinets open, the floor covered with broken plates. An icon of Saint Stanislaus of Poland lay in an open drawer, as if it had been hidden there and then discovered.

Poland, thought Lucius. Galicia . Somewhere, in the woods, they must have crossed the border. On a table, inexplicably, was a beautiful ceramic music box, which played an unfamiliar tune. The bed had been lanced open and emptied of its straw.

They kept the horses inside, in the dining room. Gathering bedstraw, tearing off the last remaining doors from the cabinet, the hussar lit a fire, killed and skinned the rabbits, and boiled them in a pot he carried on his horse. Without his mask, his face looked drawn and hollow now, and Lucius saw he ate only tiny bites. “Are you sick?” he asked at last. The man grunted, but didn’t reply. When they’d finished eating, they lay down, clothed, beneath a single blanket. Lucius remained awake. The anesthetic had begun to wear off, and his wrist was throbbing. Now he regretted his ambition to push on. How far was Lemnowice? He had enough cocaine for one more day. Constantly, he wiggled his numb fingers, worried again about a compression of the nerve. But the room was freezing—he could scarcely feel the fingers of his other hand either.

He was still awake when the hussar stirred, rose, and went to the wall to urinate. As before, he remained like that a long time, perhaps five minutes, more, before he began to groan and then to strike himself, his thighs or lower abdomen or penis—Lucius couldn’t see, only that the man did so with increasing violence.

Lucius sat up. “Corporal?”

The man stopped. His fists were balled. He lifted them high above his head and began to moan.

“Corporal?” Lucius said again. Then, very tentatively, uttering the words for the first time in his life, “I am a doctor.”

There was silence. Cautiously the man appraised him from dark, sunken eyes above unshaven cheeks.

Then tentatively, he said, “It does not come out. It is stuck… It hurts, here…”

It took Lucius only a moment to put the signs together. In the textbooks there might be a dozen different causes for an obstruction, but on the Eastern Front, with its garrison towns lined with whorehouses, there was really only one explanation in an otherwise healthy man. Back in Kraków, the clinics cared for a steady flow of men receiving urethral dilatation for gonorrheal strictures. He had seen massive, stoic soldiers reduced to sobs.

Читать дальше