“Sit,” the assistant whispered, and I did. Afraid of him and Mr. Beauchamp.

Mr. Beauchamp sat in front of me, his legs crossed, one hand on his knee, the other laid flat on the tabletop. Every so often, he lifted his hand and clicked the tabletop with his long fingernails as if he were playing the piano, and I watched as he tapped his index finger three times before he picked up his complimentary cup of coffee—black—and took a long sip.

“I’m trying to read you, Laura Ratliff,” he said, watching me.

I pulled my sleeves down over my wrists. “What do I say?” I asked.

“You’re hard to read.”

“Do you think that’s a good thing?”

“What do you think?” he asked.

Honestly, I didn’t like how he answered my question with a question.

“I don’t know,” I said slowly.

He picked up his pen and tapped it on his notebook. “So, Laura, what’s your story?”

“Are you writing a new book?” I asked, smiling.

“Maybe.”

Beauchamp hadn’t published a new book in years. He was becoming like J. D. Salinger [42] American author who is famous for writing The Catcher in the Rye, published in 1951.

or Harper Lee. [43] American author who is famous for writing To Kill a Mockingbird, published in 1960.

Withdrawn from public life—a recluse—cutting off all contact with people. Until one day he appeared in the pages of Vanity Fair . [44] A magazine that was resurrected in February 1983.

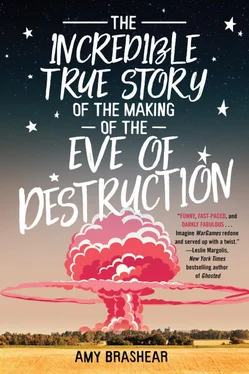

He was sitting under a lamp. A shadow from his hat sort of made a mushroom-like cloud shadow on the wall. He was the nukeman, or so many had dubbed him. He was the author that killed millions and left millions wanting more. He left the end of Eve of Destruction pretty vague. It was one of those endings that you throw the book across the room and curse the author for leaving such an unsatisfying conclusion. In the Vanity Fair article, Beauchamp admitted to the world he had been writing, and Hollywood would be filming, one of the most beloved novellas. Finally.

It is time in this nuclear climate to finish this story for a new generation to become disillusioned with the world. [45] Excerpt from Hamilton Stewart’s article, “Boudreaux Beauchamp, Obscure Author, ” Vanity Fair , January 1984.

I scooted closer to the table and asked, “Are we finally going to find out what happened to—”

He raised his hand for me to stop.

“I’m not going to answer your questions about what I’m writing,” he said.

I guess I pouted because he grabbed my hand and squeezed.

“There, there,” he said, patronizing me. “But I will tell you the title, and you can form your own conclusions. Forecast for Extinction ,” he said, leaning back on his chair. “Pretty good, don’t you think?”

There were so many ways the story could go, but he wouldn’t tell me. In fact, he went back to taking notes.

“Brunette, sixteen, pretty blue eyes—pretty green eyes,” he said, peering over his reading glasses and staring at me. “You’d be a perfect character.”

“A mutant, you mean, because the bomb went off and everyone died when the bomb went off. Remember? You wrote it,” I said.

“I do. I remember every godawful word.”

“Don’t say that. It’s one of my favorites.”

“I’m sorry.”

“Why did you stay out of the public eye for so long?”

“Nothing else to say.”

“Nothing else to say? Says the guy who’s writing a sequel to Eve of Destruction .”

He smiled, taking another drink of his complimentary coffee, and snapped his fingers for his assistant to come. “You know, Laura, your mom mentioned that you want to be a writer.”

“She did?” That was news to me.

He nodded.

“Well, to be honest, I like to write comics as a hobby. My friend Max and I are creating one.”

“Is it about nuclear war? Because there’s a market,” he says, smirking.

“It’s about superheroes.”

“You have your niche. Do you want my advice?”

“Sure,” I said, leaning forward.

“Don’t—chuck it.”

That was helpful.

“Honestly, what’s the point?” He snapped his fingers again for his assistant, who dug in his pocket for a flask and poured.

“If you want some good stuff, I can hook you up,” I said, leaning back on my chair.

“You’re a child,” he said.

I took offense to the word child .

“Okay, I’ll take the good stuff. And I assume in return you want details,” he said.

“I was just being nice, but—”

“Everybody wants something from someone,” he said. “I’ll answer your question.”

“I would like to know what happens after—”

“After?” he asked.

“After.”

“I don’t know, but don’t worry,” he said.

“Don’t worry about what?” I asked.

“Don’t worry, we won’t survive,” he said.

“We? ” I asked.

“I mean they . I mean they . Hell, I mean we too. It’s only a matter of time before we do this. It is in our nature to destroy ourselves.”

“What are you even talking about?” I asked.

“Unfortunately, humanity will one day enter a nuclear war. I hope humanity survives.”

He was on a tirade now.

“But there’s no way the human race will survive. Too many believe in the magic man in the sky while having power over nuclear weapons. We’re Homo sapiens —the only species smart enough to create its own extinction and the only species stupid enough to do it. One big bang and we all fall down. We’re going to have a ringside seat to Armageddon. Victory to the country that recovers first after a nuclear war.”

I felt sick to my stomach.

“Oh—about the book,” he said, smiling. “It seems fitting to begin with ‘The End.’”

I grabbed his cup of complimentary “coffee” and chugged.

I came running down the hall and nearly tripped over Max at my locker. He was sitting on the floor with books strewn all around him in front of lockers that had been spray-painted white.

“Who did this?” I asked, standing in front of him.

“Seniors, I think,” he said.

The FEMA pamphlet did say all interior walls should be painted antiflash white, and the walls in this hall are basically lockers. So I guessed they were doing us a favor. You know, saving lives and all.

“They’re in the principal’s office,” he added.

“Getting a lecture or an award for a job well done?”

“Your guess is as good as mine.”

I touched one of the lockers with my pinkie to make sure it was dry before sitting down on the floor beside him. I didn’t want a bunch of wet white paint on my purple shirt.

“So why are you not in homeroom?” I asked.

“I could ask you the same thing,” he said.

“I overslept.”

“Likely story,” he said, picking at his braces.

Max’s nerd transformation was now complete. Full-on metal mouth.

“Don’t even ask.” Max spoke while drooling. “I’ve got the headgear too.”

“Oh, my gosh, I’m so sorry,” I said, thankful that my parents weren’t too concerned about the well-being of my teeth. Max, on the other hand, had parentitis. “Do they hurt?” I asked.

He nodded and tossed one notebook aside and then started on another.

“Homework?” I asked.

“Yup,” he said, flipping the pages of his western civ book.

He always waited until the last minute to do his homework. He was, like, crazy smart but kind of had a hard time focusing.

“I miss the days when homework was just coloring,” he said, scratching out a sentence.

Читать дальше