While Philippe crafted his wines, I built the business that made it a viable enterprise. We rebuilt the Lacombe vineyard into something worthwhile, and Philippe passed it on to his son and sons-in-law two years before with the pride of having created a legacy to pass on to his family. Thérèse, who had inherited my mind for figures and her father’s charms, took my place running the business end of things and was already expanding the enterprise far beyond my own considerable ambitions. One day in the coming years, they would also inherit the little yellow villa with the terra-cotta shutters and the sweet drawing of a girl from Kiev over the fireplace, but it would be our home—Philippe’s and mine—for as long as we could manage it.

Now, on Red Square, the parade in honor of the anniversary of the end of the war was just beginning, and the children watched the spectacle with glee. Seven grandchildren in all, and another on the way. We watched the colorful display, and I rested my head against Philippe’s chest. He bent his head to kiss the top of mine. My red hair had become streaked with white, and the mirror reflected a woman who had seen both hardship and joy in equal measure. I loved each crease, for they had been hard won.

I sighed at the crisp uniforms as the veterans marched by to the lusty cheers of the crowd. It seemed only moments before that I had pulled up the oversized trousers and ridiculous boots, trying to make myself fit for inspection.

The crowd was young, and I wondered how different it would be if the war had been lost. If the war had never been fought. The children who hadn’t been born, the children who wouldn’t have been if things had gone differently.

I thought of Sofia and her graceful courage.

I thought of Taisiya and her brilliance and dedication.

I thought of Oksana and her tenacity and unwavering composure.

And I thought of my Vanya, who had the eyes of an artist and the heart of a poet.

They should have been with us to celebrate the victory they had willingly given their lives to ensure.

As I scanned the faces of the crowd and my own family, I wondered why I had been so fortunate. Why I had been given the chance at life—albeit one so very different from the one I envisioned—when my dearest friends and my first husband, the love of my girlhood, had not.

“Are you tired?” Philippe whispered in my ear. “We can go back to the hotel and let the others enjoy the festivities on their own.”

“No, my darling. I don’t want to leave just yet.” I squeezed his hand and looked forward onto the square.

As we strolled we came upon a gathering of veterans who had assembled in a nearby park, singing joyful songs of victory or talking quietly among themselves, reminiscing about their near misses and life on the front lines.

I found myself drawn to a chorus of perhaps a dozen female voices in one corner. They sang loudly in voices young and strong, despite the ages of the women who produced them. For the first time in decades, I wished I had my father’s violin to accompany them, but knew my feeble hands would botch the job. I gave Philippe’s hand a squeeze and left him to walk over to them and join my own wavering voice to their song.

I began exchanging letters with the surviving members of my regiment only in the last few years. After Mama died Philippe encouraged me to reestablish some connection to my motherland. Horrified by the stories coming from the aftermath of Stalin’s reign, I ignored every part of my homeland except my mother, and when she died, I let the connection go altogether. With Thérèse’s help I found Polina first, who then led me to Renata. They’d led full lives since last we spoke—Polina had been a scientist and Renata a schoolteacher, and both were now firmly entrenched in the business of grandmotherhood—but I still knew them on sight. I could see the girlish dimples still in Renata’s cheeks and the keenness in Polina’s eyes. They enveloped me in their arms as we sang the last notes of the familiar tune. My family looked baffled to see their usually reserved mother and grandmother make such a spectacle with what, to them, was a group of strangers.

I hoped they would never have to experience what we had. That they would never be called to make the same sacrifices we had. Philippe was the only one who could smile with understanding, knowing what these women meant to me.

My sisters in arms.

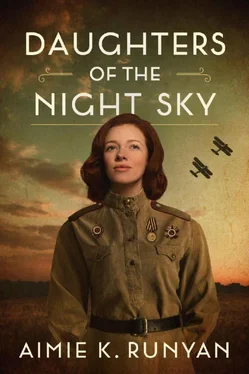

My sisters.

Let me begin by confessing three things. I am no expert on Russia. I am not a pilot. I am no expert on the Second World War beyond a casual interest that many readers share. Despite these challenges, I had to write this story. So often in history, we dismiss women’s work as secondary to men’s. The Night Witches were a shining example of women who defied expectation and served with immense valor. Once I heard about these remarkable women, I had to make their story my own.

The characters in this novel are of my own invention. Some take some personality traits from the actual crews of the Forty-Sixth Taman Guards—most noticeably, Sofia Orlova mirrors famous Soviet pilot and founder of the 122nd Aviation Group, Marina Raskova. Raskova, however, did not fly with the Forty-Sixth Taman Guards, choosing to lead the fighter regiment. I wanted to keep the founding pilot in the picture a bit longer, so rather than alter the facts, I made my own cast of characters.

On the other hand, every effort was made to respect the dates and positions where the regiment moved throughout the war. Many of the events described—such as the half-drunken scramble to fly after the women’s sanctioned celebration of the October Revolution, the furor over flare parachutes being fashioned into ladies’ undergarments, and several of the pivotal flight scenes—were adapted from anecdotes from the Night Witches themselves.

The biggest departure I make from history comes at the very end. These pilots were a very patriotic bunch, and I’ve not found evidence to support that any of them left the USSR after the war. Katya’s departure from Russia to build a life in France is her symbolic fulfillment of her promises to Vanya and Oksana to remain safe, and true to herself. She always wanted to see the world outside Russia, and I couldn’t end the story before she had her chance.

The purpose of this novel is to depict what I imagine to have been the emotional realities these women faced. There are precious few examples of historical fiction that showcase these women, and I sought to change that. If you seek nonfiction works that shed more light on the history of the time, please visit my website at www.aimiekrunyan.comfor a list of further reading.

Writing this book has been one of the greatest challenges—and joys—of my life. I sincerely hope you enjoyed it.

With love and light to all my dear readers. Clear skies.

~Aimie K. Runyan

Writing a book is a solitary endeavor in its infancy but becomes the work of many as it blooms into adulthood. I am so grateful to so many:

• Melissa Jeglinski, my inimitable agent, for encouraging this project from the outset and keeping me grounded. I couldn’t have done this without you.

• Miriam Juskowicz, for her unparalleled enthusiasm, and Danielle Marshall, for making it very clear that my book is in excellent hands.

• The entire Lake Union team for all their hard work in making this book a reality. You made my book look beautiful!

• David Downing, for his astute and detailed edits. You, sir, are a joy to work with.

• Danielle Gibeault and Dave Seymour, pilots extraordinaire, as well as the entire staff of the Flying Heritage Collection in Seattle. My profound thanks for your assistance with all things in the realm of aviation. All mistakes are mine, but they would have been far more numerous without your wisdom.

Читать дальше