“I would rather like to, yes, old chap. I expect Oadby will have a uniform ready for me to walk out in.”

“He will, for sure. Good man, that one.”

“Reliable. Can’t ask for a lot more than that.”

“Knows his way about as well. If he gives advice, it will probably be worth listening to, Naseby. My own chap, Silas, is the same. Been in the Andrew for damned near thirty years, been everywhere and done everything – a font of information.”

Oadby had a walking out uniform ready, correct rank markings and DSO ribbon precisely placed on the breast.

“Need to get hold of another pair of shoes, sir. These are a bit beyond it for walking-out, sir. Need to go to working use, sir.”

“Next time I go home, Oadby. The local man there has got my lasts made up. I suppose I could send a letter ordering a pair made for me, ready to pick up.”

“Yes, sir. Two pairs of black patent, sir. Might be as well to order up a pair of boots, sir. Liable to get muddy out on the field. Boots will be warmer in winter as well.”

“Calf high? Not up to the thigh?”

“Calf should do, sir. Might consider riding leathers, sir. Not uniform, though.”

“No. Too much of a good thing, Oadby. Stick to boots.”

The letter was quickly written and addressed. Oadby would take it to the post.

“Right, sir. Tender is waiting outside, sir. Mr Griffiths has gone off to the station already, off to London for the day, to his family.”

“As he should. The papers have made some mention of him using rifle and machine gun, ‘the skills of a sniper nurtured in the African bush’. True, in fact, but they make it sound so much more than life size.”

“That’s what they are there for, sir. If you want the truth, don’t read the newspapers.”

“What do you do, Oadby?”

“Ask somebody what was there, sir.”

“They’ll just tell you it was a cockup.”

“That’s right, sir. Nine times out of ten, that is. The tenth time, it didn’t happen at all.”

There was no gain to arguing with lower deck wisdom, especially when it came so close to the truth.

Mr Hawes-Parker was stood peering at the sky when Peter arrived.

“’Morning, Naseby. Do think it’s going to rain in the next hour?”

“Probably, yes, sir.”

“That’s what I thought. No cutting the grass today. Three rings up, I see, and a very respectable piece of ribbon! You did well, young man.”

“The right place at the right time, sir.”

“And doing the right thing. What’s the chance of getting another?”

“Almost none, sir. We are not really there to get them – our job is to be seen by them so that they stay underwater. They can only catch up with ships on the surface. They are too slow submerged. They go under to make their final approach. If we can keep them down at a distance, they will not catch our ships. We can force them to work at night only, in effect. In the Channel, that means they will sink very little.”

“Good. Long hours of patrol and nothing to show for it?”

“None of our ships sunk, sir. That’s all we need to show.”

“Are you too senior to pilot a balloon now?”

“In theory, yes, sir. While we are short of pilots, no.”

“Better come inside, I’ve kept you out here too long nattering. My granddaughter will be waiting to see you.” They progressed slowly to the door. “That midshipman of yours did well, Naseby. Brought up in Africa?”

“Went out to the Gold Coast with his parents – merchanting cocoa and palm oil, I believe, came back in early ’14. He grew up there playing with the locals and looked after by the guards. He’s a good shot with a rifle and knew what to do with the Lewis. Older than his years – I doubt he’s seventeen yet he carries himself like a man. I much suspect that the local girls taught him a lot more than one might expect a youngster of that age to know – he has that sort of confidence about him, you know, sir?”

“Saw it in some of my own ensigns, Naseby. Some of ours were country lads and had learned an awful lot in the hay barns with the lasses; others had come from a school and were very little boys. The difference was obvious, as you say. Saw a bit of Africa myself. Sent my papers in after the Zulu War. Not a lot of choice in the matter. My regiment was supposed to be guarding the Prince Imperial on the day the damned fool got himself killed, going out without orders and without his guard. The bloody newspapers howled for blood and had to get it.”

Peter made no comment – there was nothing sensible to be said.

Josephine was sat decorously at the worktable in the second sitting room, making a show of embroidery. She was not doing especially well, judging by the grin on her grandmother’s face.

“Commander Naseby! We hoped, that is I wondered if you might be able to call today.”

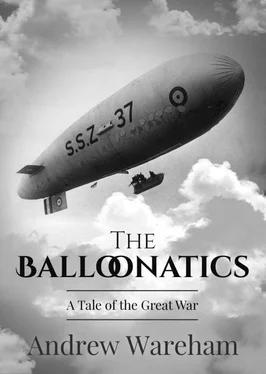

“Raining and gusty winds, actual squalls not impossible. The blimps are tucked away in their hangars and their pilots are at leisure, for the first time in two weeks!”

“Is it actually hard labour, flying a balloon? One sees pictures of the old sailing ships with men heaving on ropes and such…”

“No, not hard in that sense. Merely long hours of sitting in a cold cockpit, watchful all the time, trying to keep alert. It is not demanding in the physical sense. It is cold and the rain always trickles down the back of one’s neck and the wind finds some place where one’s pullover does not quite cover the skin. Tedious and tiring yet one must remain awake and watchful at all times. On a dry day with little wind, the sun shining on one’s back – then it is a pleasure cruise, a holiday excursion. For some reason, those days are rare in England!”

She knew that to be so.

“Are you to continue as a pilot despite your more senior rank, Commander?”

“While we are short of pilots, I must. We shall have the better part of forty blimps flying by the end of this month and we have one half of that number of properly trained pilots yet. I am one of the senior men – and I have fewer than two hundred hours of flight to my name. When I was given my watch-keeping certificate as a midshipman, immediately before I was promoted sub, I had, at a rough guess, more than two thousand hours in total on a ship’s bridge. We are inventing our skills as we go. I must continue to fly for many months yet, until we know what we are doing.”

“Chasing submarines all the while, Commander?”

The question came from old Mrs Hawes-Parker, sat back observing the formality between the two with some amusement.

“That is our main function, ma’am. There has been some talk of using us to spot for bombarding ships of the Dunkirk Squadron, I understand. That may come to something, or it may just be talk. In the same way, there has been speculation of the possibility of blimps accompanying the Grand Fleet in a reconnaissance role. I think that must wait until the new, bigger Coastals come into service.”

“Speculation, as you say, Commander Naseby. You expect to remain with the RNAS, for the remainder of your career?”

“Probably, ma’am, but in wartime I shall go where I am sent with nothing to say on the matter. The RNAS seems most likely and has the old advantage of the big fish in the small pool.”

“Very few Commanders and only one who has a submarine to his credit – that can only be useful to you, young man.”

“It must be, ma’am.”

“So it must. Come now, you should not be sitting around in here talking to an old woman. Take my granddaughter out for some fresh air and buy her a lunch as well. I shall see you later.”

Peter gained the impression that a decision had been taken. He had been accepted as a suitor, was regarded as a fit and proper person to marry into her family.

Читать дальше