Josephine ran for coat and scarf, was ready to go in a bare five minutes, to the amaze of the menfolk.

“A walk to the hotel, Josephine?”

“No. To the fishing harbour and the little restaurant there. It is owned by an Italian family and does wonders with crabs and lobster and flatfish. It is a treat we sometimes indulge in. The distance is a little far for my grandparents to walk and so we have to arrange a cab.”

He found himself holding her hand as they walked, rather fast for so early in their acquaintance but very pleasant.

They passed a shop towards the harbour, closed down and windows boarded up, graffiti scrawled in red paint.

“‘Bloody Huns’. Who were they?”

“The tailor, Mr Schultz. He has lived here all his life. His father came from Germany in the 1860s, so my grandfather said. His windows were smashed repeatedly last year and he gave up and left the town. I cannot think that to be right, Peter!”

“It is not. I have heard of the little German dogs, the Dachshunds, being killed for being Huns. People can be extremely unpleasant on occasion, and remarkably stupid.”

Lunch was all that she had promised, a meal that brought recollections of the Mediterranean where his ship had cruised in 1912. His reminiscences provided plenty to talk about.

“A pity we have no Russian restaurants that I know of to bring back memories of St Petersburg, Josephine.”

She shook her head.

“No. The Russians have no food of their own, the cuisine was all French, and very good. Those of us who had access to food, ate well.”

“You mentioned bread riots, I remember.”

“There will be revolution before long, because of those riots, Peter. The peasants are treated like animals, like dogs. If you are cruel to a dog, sooner or later, it will bite.”

It was a simple analysis and wholly convincing.

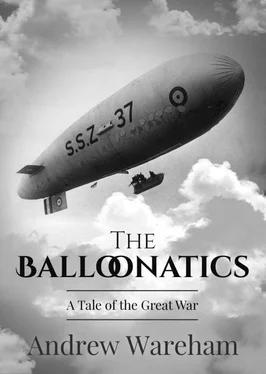

Peter called for the bill. The waiter came with a copy of the Daily Mail, opened to a large photograph of Peter stood in front of SS9.

“If you would autograph this, sir, we will put it up on the wall. Shoreham’s own war hero, sir. There is no bill.”

It was embarrassing; there was no alternative except to be churlish. He could fling a ten shilling note down on the table and storm out – it would be a shockingly ill-mannered response. He managed a smile and took the proffered fountain pen.

“Across the corner, sir. Thank you, sir. We shall have this framed, sir.”

Josephine said nothing, aware of Peter’s emotions, unable to think of anything useful to offer.

They took their coats and smiled their best and thanked the proprietor and walked off to the harbour.

“I did not expect that, Josephine.”

“No more did I… You were right to sign it, and to smile kindly, difficult though that must have been.”

“It was. They meant nothing other than the best. How disgraceful I would have been to refuse them!”

A slow walk back to the house.

“May I call in future, Josephine. Often, perhaps?”

“You will be more than welcome, Peter.”

They said no more on personal matters, it was far too soon to make any expressions of affection. The Crossley arrived for him soon after returning, carried him off to Polegate reflecting on his day, on balance enjoyable.

“Beg pardon, sir. Mr Troughton would like a word on your return.”

Peter made his way to the office, found Troughton in process of putting together his personal belongings.

“Folkestone for me, Naseby. I am to be the Grand Panjandrum, in charge of the stations along the south Kent and Sussex coasts. They have given me a fourth ring!”

“Post Captain, sir. My most sincere congratulations.”

“Thank’ee, Naseby. You are to continue as OIC Flying and another body will come into this office. You will be senior on the flying side under me. I expect to be on the telephone to you most days. As yet, all is up in the air, literally. The weather is set foul for the next two days, so you should go home for a forty-eight hour pass. You will be busy on your return.”

That sounded much like an order. Peter wondered why he must go home. It was not worth arguing about – he might be reading too much into a simple offer of two days of freedom.

He took the train to Brighton next morning and then express to London, was knocking on the front door by mid-morning. A maid gave him entry, to his surprise. There had always been a manservant as well as the butler.

“Charles has gone to the war, sir. Difficult to find a manservant now, sir.”

He had not expected a maid to be so talkative either. Times were changing.

His mother and Minnie were sat in their workroom, labouring over a mass of small boxes which they were filling from various open cartons.

“Peter! I did not hope to see you so soon. Are you well, my dear?”

He could see no reason why he should not be.

“Whatever are you doing? Have you taken up smoking, Mama?”

He gestured at the literally hundreds of packets of Woodbines cigarettes, one of the cheapest brands.

“A Christmas present for the troops, from the Committee to go to every volunteer from the borough. The funds permitted a box each with sixty cigarettes and two bars of chocolate and a balaclava helmet and a woollen scarf. I have the privilege of packing the boxes, being Chairlady of the Committee. They must go as soon as possible, being some four months late already. The previous chair was not an organiser!”

It would be June by the time the presents actually got to the men; no doubt they would still be welcome.

“Jenny not with you?”

“She is training to be a nurse, is at the hospital six days a week now. She was more upset than I had realised at her young man dying. She wishes to do her bit, she says.”

That was wholly unexpected – his sister was to be a debutante, not a nurse caring for the wounded of the war. He could not like it, was not about to object.

“My father approves, Mama?”

“He could hardly do otherwise, Peter. There would be such a fuss if he moved to prevent her from serving.”

He said no more on the topic.

“What of you, Minnie?”

“I am learning to drive the car, Peter. When I am competent, I shall join one of the Auxiliary Services. I cannot be a nurse – the blood and the smells and everything! I can be useful, doing a job that will free a man to fight.”

Perhaps he had been sheltered from the changes that were affecting the country, too tied up in his own little world to know what was happening in the country as a whole.

“What of you, brother? Who is this young lady in Shoreham the papers made so much of?”

“Minnie! I told you not to plague your brother when he came home! He must be tired and in need of rest more than anything. After his experiences…”

“No need to worry about me, Mama! The whole business was over in a minute, just a sudden burst of activity and then all finished, a matter of tidying up, no more. The afterclap, the fuss and bother with admirals and the Prince and the newspapers has been far more wearing an experience than the brief fight.”

If her son said so, then she would not argue. She thought him to look older, leaner in the face, strained; he was working long hours and out in an open cockpit, from the photographs in the newspapers, all of which were safely tucked away on her shelves.

“Your face is weather-beaten, Peter. Exposed to the wind all day, it must be. Much like the old sailing ships. I remember my grandfather looking much the same, and he had been retired some little while when I was born. He was a post captain and had a sailing two-decker, one of the last not to have steam as well. Not to worry – there is nothing to be done about it. You look very fine with the three rings on your sleeve – an early promotion.”

Читать дальше