“Diving hard, Griffiths.”

The boy grabbed hold of his handrail as the nose pointed down. He eased the rifle to his shoulder as they came within a mile of the submarine, still making her way unconcerned. He could see lookouts scanning the horizon, staring out to sea, none with their heads up. Attack from the air was still almost unknown. He cocked the Lewis, ready for the command.

“Spotted us! Fire, Griffiths!”

Perhaps a thousand yards, five cables, distant and at a height of six hundred feet, still diving in the leisurely fashion of a blimp.

Griffiths released four aimed shots from his magazine rifle, dropped it at his side and put his shoulder to the Lewis, emptied its forty-seven rounds in a sustained burst.

“Hits, sir! Men down in the conning tower. They can’t clear it!”

Peter reached across from the yoke, took a grip on the toggle of the bomb release, watched as he came over the submarine, just beginning its dive. He dropped from one hundred feet, the single one hundred and twelve pound bomb falling cleanly away, nose first.

Griffiths was hanging out of his cockpit, staring behind them.

“Hit, sir! Just in front of the conning tower!”

There was a loud explosion, a great cloud of spray and the submarine rolled onto its side before slipping under the water. A few seconds and the spray cleared and they watched as oil gouted up to the surface.

“Got her, sir! She’s sunk, sir!”

“Probably. Send the report. ‘Bombed surfaced submarine. Observed hit. Submarine submerged. Large oil slick forming’.”

Griffiths sat down to the wireless, standing as soon as he could to scan their scene of triumph.

“Acknowledged, sir. ‘Well done’.”

They circled the oil slick, watching for signs of movement. There was a sudden big bubble of air, as if the compressed air reservoirs had ruptured.

“Looks like a body, sir. Showing white.”

Peter peered and agreed that it seemed to be flesh.

He scanned the horizon.

“Destroyer closing at speed. Must be pushing thirty knots.”

A new ‘M’ class, he thought, coming to assist as necessary. Peter fired a green flare, to confirm his friendly status. He had not forgotten the destroyer that had mistaken him for a Zeppelin a fortnight previously.

The destroyer circled close to the oil slick and dropped a boat which recovered four bodies and some items of uniform and mess tins – it seemed that the submarine had been enjoying a late breakfast when they hit it.

“Light signal, sir. Can’t get all of it. ‘Sub sunk. U 22 on cap tallies. Good shooting.”

“Acknowledge – wave to them.”

They did not have an Aldis signal lamp, preferring not to carry the additional weight of lamp and batteries.

“Signal return to base to rearm, Griffiths.”

Peter put SS9 into her slow turn and climbed away from the scene of his victory, heading on a direct line for Polegate.

They landed to roars of cheering, men dancing and shouting on the field and almost fighting each other to take a grip on the nacelle and walk them in.

Troughton was there, waving his cap and yelling with the rest.

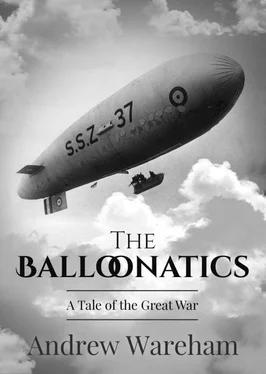

“Got one, Naseby. All our own! First battle honour for Polegate and for the RNAS, for any of the blimps.”

“Griffiths did well with his rifle, sir. Shot a couple in the conning tower so they could not dive fast. Hid up in the clouds, sir, and they weren’t looking for attack from the air. Dropped at about a hundred feet, hit her just in front of the tower. Bloody great bang!”

“I should think it was, man! Lucky it hit in front of the tower – shielded you from the blast, I would think.”

Pickles came across to say that he wanted to put SS9 inside where he could work on her.

“Picked up a few bomb fragments in the nacelle, towards the rear end, and I want to look at the envelope, see if there might be some tiny holes there.”

“Off the duty list for the rest of the day, Pickles.”

Peter was not displeased to be idle for a few hours. The shock of the sudden action was just hitting home, now that he had nothing to do.

“Tea, Naseby! And you, Griffiths. Sit down and write up your reports – they will be wanted soonest.”

They sat at tables in the mess to produce their accounts of the morning’s action, necessarily brief. Cooks and stewards vied with each other to run hot tea to them, quickly followed by toast and marmalade for a second breakfast. A carpenter appeared, one of the riggers from the hangar, and took measurements of a clear space on the wall.

“Honours Board, sir, for Polegate.”

It was all somewhat embarrassing, but done with the best of intentions, the whole base sharing in their great and only half-expected success. They had known they were keeping submarines down, had not really thought they might sink one.

Troughton appeared at five minute intervals, it seemed.

“Congratulations, Polegate, C-in-C Dover Patrol.”

“Well done, Polegate, C-in-C Portsmouth – makes a change from sinking admirals.”

Peter laughed – that story would never leave him – he would always be the officer who ran down the Admiral in his barge.

“From the Admiralty. Vice-Admiral in charge of Operations, Channel Coast, will visit this afternoon, with guest. Well done all. In the best traditions of the Royal Navy. Naseby and Griffiths, best working dress.”

“Why, sir?”

Troughton shrugged – he had not the faintest idea.

“You are to be smart but sea-going. I can only imagine they want a photograph. I wonder why?”

Word was passed to the CPOs – there would be brass on the field, of the most senior. Everything that could be quickly polished must shine.

“We are to recall the patrolling blimps, Naseby. All to be present on the field, crews in place, bombed up, Lewises mounted. Do you think they are bringing Royalty with them, Naseby? Putting on a display, sort of thing?”

It was possible.

They ran and swore and tucked everything unofficial out of sight and the cooks baked a cake and telephoned for fresh bread from the baker in Folkestone and dug out ham from their private stores to make official sandwiches for visitors, according to regulations.

“We’ve got nothing worth drinking in the cellar, Naseby! If there is Royalty, we can’t give him table wine, red, official issue for the drinking of.”

The prospect was appalling – they would never live it down.

“Who’s got a nose for a wine bottle?”

Crawley, the chemist, admitted to knowing his wines – his father had a cellar and had brought him up to appreciate a good glass. He was sent off in a Crossley with a blank cheque from Peter to quickly locate the best wine merchant in Brighton, a far more fashionable town than Folkestone, and bring back half a dozen cases of the best.

“Bloody good thing you’re a banker, Naseby! Helps to have a bit of money sometimes.”

It was unimportant, Peter responded.

“I don’t use a half of my allowance most years, sir. It just sits in the account, building up for when I need it. Be different when, if that is, I get married.”

“Oho! Thinking of taking the fatal step, Naseby?”

“Considering it, sir. Got to know the most attractive young lady just recently. Early days yet and she’s of no great age. Met her grandparents couple of weeks back – when the wind was high, you recall. Pleasant people. Mother dead, father in the embassy in the States.”

“Sounds good to me, Naseby. If you want my advice – and there’s no reason why you should – go for it. Better far married now than regretting in five years that you never quite got around to it. Not to worry! Is that your report? Good. I’ll tuck it in with mine and we shall have all the paperwork squared away. Fitzjames won’t be coming across, by the way. He was carted off to hospital yesterday, poor chap, at Haslar. From what they say, I doubt he will come out. I’ve sent a telegram – buck him up a bit to know of our success. Don’t know what’s to be done for running the bases now.”

Читать дальше