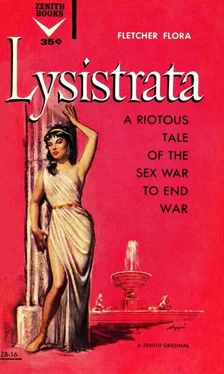

Fletcher Flora - Lysistrata

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Fletcher Flora - Lysistrata» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1959, Издательство: Zenith Books, Жанр: Историческая проза, comedy, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Lysistrata

- Автор:

- Издательство:Zenith Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1959

- Город:New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Lysistrata: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Lysistrata»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Seven months of lonely days and empty nights — of aching heart and throbbing loins. Seven months of longing.

But now a strange smile played around her lips.

Tonight he was coming home—

Lysistrata — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Lysistrata», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“You still haven’t told me why the Mistress should breakfast so early.”

“Because she is going out on an important mission, that’s why.”

“Indeed! And I suppose she always confides in you concerning matters of importance?”

“Yes, she does. We are really quite intimate, as I have told you, and I am allowed to know what is going on.”

“Pardon me, please. I didn’t dream that you were of such tremendous importance around here.”

“You would do well to learn it and remember it the next time you are inclined to molest me.”

By this time, Theoris had inched her way to the bread. Helping herself, she moved with more boldness to the supply of wine, from which she also helped herself. She then moved toward the door with an exaggerated swaying of her slender hips. The cook, plainly uncertain as to the truth of her story, but strongly inclined to believe that she was brazenly taking the bread and wine for her own use, watched her for a minute in indecision. Then, regaining his assurance a fraction of a second too late, he made a powerful swipe at her behind that would certainly have knocked her sprawling if it had landed. With a skip and a squeal, holding tightly to the bread and wine, Theoris reached the door. Turning, she spat in the direction of the cook and then scurried back through the court to Lysistrata’s room.

Lysistrata had already returned from her bath and was clothed in the white peplos. She looked at Theoris curiously.

“Why are you breathing so hard?” she said. “Have you been running?”

“I know you wish to be about your business, so I hurried.”

“On the contrary, it seems to me that you took an unconscionable time.”

“I’m truly sorry, Mistress. I had to convince the cook, who was already in the kitchen, that I was not stealing the bread and wine for myself.”

“Well, no matter. In order to save time, I’ll eat while you are braiding my hair. Will that disturb you?”

“No, Mistress.”

While Lysistrata ate sparingly of bread dipped in wine, for she was far too excited to have an appetite, Theoris deftly braided her hair and bound the heavy braids around her head. After Theoris was finished, Lysistrata stood up and drew her heavy cloak about her shoulders.

“Now I must leave,” she said. “How long I shall be gone is impossible to predict. Theoris, my good companion as well as my slave, I charge you to look after my affairs until I return. And please don’t produce any tears, for they are not required. Do you think you can handle things competently?”

“I can handle everything, Mistress, except possibly the cook. I am not sure of the cook.”

“It’s true that he’s a sullen and insolent fellow, besides being a natural liar. I often find him difficult to handle myself. I advise you to stay out of the kitchen as much as possible, which is usually my own policy except in cases of strict necessity.”

“I shall do as you advise, I assure you, for he is in fact extremely naughty, as well as being the other things you mentioned.”

“Oh, well, naughtiness often lends a little interest to things if it is controlled properly. Good-by, Theoris.”

“Good-by, Mistress, and good luck.”

Turning away, Lysistrata went out through the rear garden into the street. Theoris sat down and began to finish the bread and wine that her mistress had left. She wondered how far the cook was likely to go in response to her baiting, and more important than that, how far she was willing for him to go.

11

The air in the streets was chill. Holding her cloak about her, Lysistrata walked swiftly in the direction of the Acropolis, sustained by a rising sense of exhilaration. In the distance ahead of her, touched by a flickering of thin light, a Scythian policeman, armed with bow and arrows, crossed the street on his vigilant patrol. Reaching her through darkness from another street, there came the heavy rumbling of a wooden cart, a farmer of Attica on his way to market.

In the center of the city, a vital organ that Lysistrata could feel but not see, the slumbering marketplace seemed to send out through the streets, which were its arteries, the slow and rhythmic beat of its powerful pulse. Lysistrata felt the pulse as a supplement to her own, throbbing in her wrists and temples and breast. In her heart she felt the breath of Athens, in her flesh and bones its restless stirring before waking. It was very exciting to be abroad in the streets, a part of activity that was all too restricted in the dull days of respectable wives. Respectability was, in fact, an honorable estate in which she shared reluctantly. She did not wish to be a man, since this would entail the loss of advantages she now possessed, but she wished often for a man’s freedom, or even the relative freedom of the hetairai or the flower girls of the market, who were permitted to be in the thick of things. In the old days, she knew, the women of Athens had been allowed to move about and play a part in affairs, and they had then exerted an influence which had since been lost. Manners and customs had changed, as they do in time, and the modern wife was expected to remain circumspectly hidden within the walls of her house, which was, in Lysistrata’s judgment, dull business indeed.

Reaching at last the hill of the Acropolis, a rocky projection rising five hundred feet above the plain of Athens, she began to ascend the zig-zag terraced path to the summit. She paused at intervals to rest, but even so she was breathing hard from the climb when it was finished, and her breath was taken even more, as it always was, by the beauty of the Propylaea, which had been begun in the time of Pericles a quarter of a century before. Above her rose the six Doric columns of the portico, and beyond the portico, still filled with shadows of night in the final short while before dawn, was the great entrance hall itself, divided into three aisles by rows of Ionic columns. At the far end of the hall was the wall of five gates, beyond which was another portico identical to this, and from which one might look across the Acropolis and see enough of beauty in one small space to last for life and light a world. There stood the serene Parthenon, raised to the glory of the patron goddess of Athens. There stood the Erechtheum of ineffable grace. There stood the giant image of Athene Promachos, lifting her head almost fifty feet above the crest to stare eternally out to sea. There stood, in temple and shrine and image of deity, the best art of Athens. And it was almost beyond credence, Lysistrata thought, that the men who fostered it and loved it and paid for it could be capable at the same time of behaving perpetually like imbeciles.

After reaching the crest, Lysistrata had scarcely caught her breath before she heard her name called clearly. A moment later Nausica came out of the shadows of the Propylaea. She hurried down the broad flight of stairs with her elbows threshing at her sides as if the thinning darkness were a material resistance through which she had to beat her way. As she came near, it was evident that she was quite exuberant.

“There you are, Lysistrata,” she said. “I have been waiting and waiting for you, and I have been positively on the verge of prostration for fear something had occurred to upset our plans.”

“Not at all, Nausica. At least, not to my knowledge. You are up and about your duties early enough, I must say. And that is more than I can say for those who are pledged to meet me here for council. It’s simply disgusting, that’s what it is. If they had been called out to celebrate a festival, they would be cavorting and displaying themselves in all the streets by this time. As it is, they are probably lying sluggishly in bed.”

“Perhaps you do them an injustice. After all, it is not a simple matter to get promptly away from home, especially if one has a suspicious husband to evade or children to provide for.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Lysistrata»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Lysistrata» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Lysistrata» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.