"Adieu," he said, "this is goodbye. I'll never forget you, never."

She stood silent. He looked at her and saw her eyes full of tears. He turned away.

"I'm going to give you the address of one of my uncles," he said after a moment. "He's a von Falk like me, my father's brother. He's had a brilliant military career and he's in Paris working for…" He gave a very long German name. "Until the end of the war, he will be the Commandant in greater Paris, a kind of viceroy, actually, and he depends on my uncle to help make decisions. I've told him about you and asked that he help you as much as he can, if you ever find yourself in difficulty; we're at war, God alone knows what might happen to all of us…"

"You're very kind, Bruno," she said quietly.

At this moment she wasn't ashamed of loving him, because her physical desire had gone and all she felt towards him now was pity and a profound, almost maternal tenderness. She forced herself to smile. "Like the Chinese mother who sent her son off to war telling him to be careful 'because war has its dangers,' I'm asking you, if you have any feelings for me, to be as careful as possible with your life."

"Because it is precious to you?" he asked nervously.

"Yes. Because it is precious to me."

Slowly, they shook hands. She walked him out to the front steps. An orderly was waiting for him, holding the reins of his horse. It was late, but no one even considered going to bed. Everyone wanted to see the Germans leave. In these final hours, a kind of melancholy and human warmth bound them all together: the conquered and the conquerors. Big Erwald with the strong thighs who held his drink so well and was so funny and robust; short, nimble, cheerful Willy, who had learned some French songs (they said he was a real comedian in civilian life), poor Johann who had lost his whole family in an air raid, "except for my mother-in-law," he said sadly, "because I've never had much luck…" All of them were about to be attacked, shot at, in danger of dying. How many of them would be buried on the Russian steppes? No matter how quickly, how successfully the war with Germany might finish, how many poor people would never see the blessed end, the new beginning? It was a wonderful night: clear, moonlit, without even a breath of wind. It was the time of year for cutting the branches of the lime trees. The time when men and boys climb up into the beautiful, leafy trees and strip them bare while, down below, women and girls pick flowers from the sweet-smelling branches at their feet-flowers that will spend all summer drying in country lofts and, in winter, will make herbal tea. A delicious, intoxicating perfume filled the air. How wonderful everything was, how peaceful. Children played and chased one another about; they climbed up on to the steps of the old stone cross and watched the road.

"Can you see them?" their mothers asked.

"Not yet."

It had been decided that the regiment would assemble in front of the château and then parade through the village. From the shadow of doorways came the sound of kisses and whispered goodbyes… some more tender than others. The soldiers were in heavy helmets and field dress, gas masks hanging from their necks. The awaited drum roll came and the men appeared, marching in rows of eight. With a final goodbye, a last blown kiss, the latecomers hurried to take their pre-assigned place: the place where destiny would find them. There was still the odd burst of laughter, a joke exchanged between the soldiers and the crowd, but soon everyone fell silent. The General had arrived. He rode his horse past the troops, gave a brief salute to the soldiers and to the French, then left. Behind him followed the officers, then the grey car carrying the Commandant, with its motorcycle outriders. Then came the artillery, the cannons on their rolling platforms, the machine-guns, the anti-aircraft guns pointing at the sky, and all the small but deadly weapons they'd watched go by during manoeuvres. They had become accustomed to them, had looked at them indifferently, without being afraid. But now the sight of it all made them shudder. The truck, full to bursting with big loaves of black bread, freshly baked and sweet-smelling, the Red Cross vans, with no passengers-for now… the field kitchen, bumping along at the end of the procession like a saucepan tied to a dog's tail. The men began singing, a grave, slow song that drifted away into the night. Soon the road was empty. All that remained of the German regiment was a little cloud of dust.

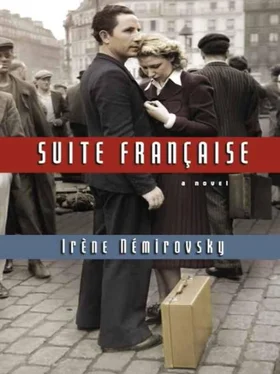

Irène Némirovsky's handwritten notes on the situation in France and her plans for Suite Française, taken from her notebooks

My God! what is this country doing to me? Since it is rejecting me, let us consider it coldly, let us watch as it loses its honour and its life. And the other countries? What are they to me? Empires are dying. Nothing matters. Whether you look at it from a mystical or a personal point of view, it's just the same. Let us keep a cool head. Let us harden our heart. Let us wait.

21 June. [1] Conversation with Pied-de-Marmite. France is going to join hands with Germany. Soon they will be calling up people here but "only the young ones." This was said no doubt out of consideration towards Michel. One army is crossing Russia, the other is coming from Africa. Suez has been taken. Japan with its formidable fleet is fighting America. England is begging for mercy.

[1] 1941, given the historical indications contained in these entries. (Unless indicated, the footnotes are the translator's.)

25 June. Unbelievable heat. The garden is decked out with the colours of June-azure, pale-green and pink. I lost my pen. There are still many other worries such as the threat of a concentration camp, the status of Jews etc. Sunday was unforgettable. The thunderbolt about Russia [2] hit our friends after their "mad night" down by the lake. And in order to [?] with them, everyone got drunk. Will I write about it one day?

[2] Germany invaded the USSR on 22 June 1941.

28 June. They're leaving. They were depressed for twenty-four hours, now they're cheerful, especially when they're together. The little dear one sadly said, "The happy times are over." They're sending their packages home. They're overexcited, that's obvious. Admirably disciplined and, I think, no rebellion in their hearts. I swear here and now never again to take out my bitterness, no matter how justifiable, on a group of people, whatever their race, religion, convictions, prejudices, errors. I feel sorry for these poor children. But I cannot forgive certain individuals, those who reject me, those who coldly abandon us, those who are prepared to stab you in the back. Those people… if I could just get my hands on them… When will it all end? The troops that were here last summer said "Christmas," then July. Now end '41.

There's been talk here about de-occupying France except for the no-go area and the coasts. Carefully rereading the Journal Officiel [3] has thrown me back to feeling the way I did a few days ago,

To lift such a heavy weight

Sisyphus, you will need all your courage.

I do not lack the courage to complete the task

But the end is far and time is short.

The Wine of Solitude by Irène Némirovsky for Irène Némirovsky

[3] The Journal Officiel reported all laws, decrees, decisions etc. adopted by the government. At this point in time, Marshal Pétain had already been given constitutional powers. See Robert O. Paxton, Vichy France, Old Guard and New Order 1940-1944, Knopf, 1975, p. 32.

30 June 1941. Stress the Michauds. People who always pay the price and the only ones who are truly noble. Odd that the majority of the masses, the detestable masses, are made up of these courageous types. The majority doesn't get better because of them nor do they [the courageous types] get worse.

Читать дальше

![Константин Бальмонт - Константин Бальмонт и поэзия французского языка/Konstantin Balmont et la poésie de langue française [билингва ru-fr]](/books/60875/konstantin-balmont-konstantin-balmont-i-poeziya-francuzskogo-yazyka-konstantin-balmont-et-thumb.webp)