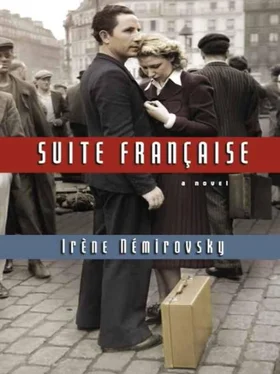

Frowning slightly, Arlette studied her fingernails. The ten little sparkling mirrors seemed to put her in a pensive mood. Her lovers knew that when she contemplated her hands in this reflective, malicious way, it meant she was about to express her opinion on things like politics, art, literature and fashion, and that, in general, her opinions were insightful and just. For a few seconds, in this little garden in bloom, while bumblebees gathered pollen from a bush with scarlet bell-shaped flowers, the dancer imagined the future. She came to the conclusion that for her nothing would change. Her wealth consisted of jewellery-which could only increase in value-and property (she'd made some good investments in the Midi, before the war). Yet they were mere trimmings. Her principal assets were her legs, her figure, her scheming mind-things vulnerable only to time. But there was the rub… She immediately thought of her age and, taking a mirror from her handbag in the way that you touch a good-luck charm to ward off evil spirits, looked carefully at her face. An unpleasant thought occurred to her: she used nothing but American make-up. It had been difficult to get hold of any for a few weeks now. That put her in a bad mood. So what! Things might change on the surface but underneath everything would be the same. There would be new rich men, just as there always were after great disasters-men prepared to pay dearly for their pleasures because their money had come easily and so would love. But please, dear God, let all this chaos end quickly! Please let us get back to a normal way of life, whatever it might be; these wars, revolutions, great historical upheavals might be exciting to men, but to women… Women felt nothing but boredom. She was positive that every woman would agree with her: they were tired of crying, bored to death by all these noble words and noble feelings! As for men… it was hard to know, difficult to say… In some ways those simple souls were incomprehensible, whereas for at least fifty years women had been concerned only with the commonplace, the ordinary… She looked up and saw the owner of the little hotel leaning out of the window, looking at something. "What is it, Madame Goulot?" she asked.

"Mademoiselle," the woman replied in a solemn, trembling voice, "it's them… they're coming…"

"The Germans?"

"Yes."

The dancer was about to get up to go to the gate so she could see down the road, but she was afraid to in case someone took her deckchair and her spot in the shade, so she stayed where she was.

It wasn't the Germans who were coming but one German: the first. From behind closed doors, through half-closed shutters, from attic windows, the entire village watched him arrive. He stopped his motorcycle in the deserted village square. He had on a green uniform, gloves and a helmet with a visor. When he raised his head, you could see a rosy, thin, almost childlike face. "But he's so young!" murmured the women. Without actually realising it, they were expecting some vision from the Apocalypse, some terrifying, foreign monster. Since he looked around expectantly, the newsagent, who had fought in '14 and wore his Croix de Guerre and military medals on the inside of his old grey jacket, came out of his shop and walked towards the enemy. For a moment, the two men just stood there, face-to-face, without saying a word. Then the German took out a cigarette and asked for a light in bad French. The newsagent replied in bad German; he had been among the occupying forces in Mainz in '18. There was such total silence (the whole village was holding its breath) that you could hear each and every word. The German asked for directions.

The Frenchman replied, then became bolder: "Has the armistice been signed?"

The German threw open his arms. "We don't know yet. We hope so," he said.

And the humanity of his words, his gesture, everything proved they were not dealing with some bloodthirsty monster but with a simple soldier like any other, and suddenly the ice was broken between the town and the enemy, between the country folk and the invader.

"He doesn't seem so bad," the women whispered.

He smiled and then, raising his hand to his helmet, made an unconfident, half-finished gesture: not quite a military salute but not a civilian greeting either. He glanced curiously at the closed windows for a moment, started up his motorcycle and disappeared. One after the other, doors opened and the entire village spilled out into the square until the newsagent was surrounded. Standing motionless, his hands in his pockets, he was frowning and staring into the distance. Contradictory expressions appeared on his face: relief it was all over, sadness and anger that it had all ended this way, memories of the past, fear of the future; and all these feelings were mirrored in the faces around him. The women dried tears from their eyes; the men stood silent, looking obstinate and hostile. The children, distracted from their games for a moment, turned back to their marbles and hopscotch. The sky was shining with the kind of brilliant, silvery light you sometimes find in the middle of a truly beautiful day; an almost imperceptible iridescent mist hovered in the air and all the fresh colours of June were intensified, looked richer and softer, as if reflected through a prism.

The hours passed by peacefully. There were fewer cars on the road. Bicycles still sped along as if caught up in the angry wind that had been blowing in from the north-east for over a week now, dragging with them their miserable human cargo. A little while later there was a surprising sight: cars appeared-travelling in the opposite direction from a week ago. People were going back to Paris. When they saw that, the villagers finally believed it was all over. They went home. Once again you could hear the women rattling the dishes as they washed them in their kitchens, the faint footsteps of an old woman going to feed her rabbits, even a little girl singing as she drew water from a pump. Dogs rolled around, playing in the dust.

It was an exquisite evening with clear skies and blue shadows; the last rays of the setting sun caressed the roses, while the church bells called the faithful to prayer. But then a noise rose up from the road, a noise unlike any they'd heard these past few days, a low, steady rumbling that seemed to move slowly closer, heavy and relentless. Trucks were heading towards the village. This time it really was the Germans. The trucks stopped in the village square and men got out; others pulled up behind them, then more and still more. In a few seconds the whole of the old, dusty square, from the church to the municipal hall, became a dark, still mass of grey vehicles with a few faded branches clinging to them, the remains of their camouflage.

There were so many! Silently, cautiously, people came out on to their doorsteps again. They tried in vain to count the flood of soldiers. Germans were coming from all directions. They filled the squares and streets-more and more of them, endlessly. The villagers hadn't heard the sound of footsteps in the street, young voices, laughter, since September. They were stunned by the noise emerging from this wave of green uniforms, by the scent of these healthy men, their young flesh, and especially by the sound of this foreign language. Germans poured into the houses, the shops, the cafés. Their boots clanked over the red tiles of the kitchens. They asked for food, drink. They stroked the children as they went by. They threw open their arms, they sang, they laughed with the women. Their obvious happiness, their delight at being conquerors, their feverish bliss-a bliss combined with a touch of wonder, as if they themselves could hardly believe what had happened-all this contained such drama, such excitement, that the defeated villagers forgot their sadness and bitterness for a few seconds. They just stood and watched, speechless.

Читать дальше

![Константин Бальмонт - Константин Бальмонт и поэзия французского языка/Konstantin Balmont et la poésie de langue française [билингва ru-fr]](/books/60875/konstantin-balmont-konstantin-balmont-i-poeziya-francuzskogo-yazyka-konstantin-balmont-et-thumb.webp)