She said nothing. Behind them, Frances put one tentative foot in the water.

“If you are guided by your conscience and only by your conscience then that is what we must become,” she said thoughtfully. “All of us, guided by our own consciences, coming together only when it suits us.”

“A society cannot live like that,” J replied.

“A family cannot,” Jane said. “As soon as you love someone, as soon as you have a child, you acknowledge your duty to put another’s needs first.”

J hesitated.

“The other way is the king’s way,” Jane continued. “The very thing you despise. A man who puts his own desires and needs before everyone else. Who thinks his needs and desires are of superior merit.”

“But I am guided by my conscience!” J protested.

“He could say the same,” she said gently. “If you are Charles the king, then your wishes could very well seem to be conscience and there would be no one to tell you your duty.”

“So where is my course?” J asked. “If you are my adviser this day?”

“Somewhere between duty and your own wishes,” Jane said. “Surely we can find a way for you to keep your soul clear of heresy and yet still live here.”

J’s face was bleak. “You would put your comfort before my conscience,” he said flatly. “All it is with you, is living here.”

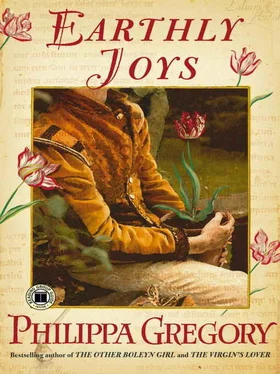

She did not turn away from him but tightened her grip around his waist. “Think,” she urged him. “Do you really want to walk away from the garden that is your inheritance? The chestnut tree which your father gave to your mother the year you were conceived? The black-heart cherry? His geraniums? The tulips that you saved from New Hall? The larches from Archangel?”

J turned his head away from her pleading face but Jane did not let go. “If we never have another child,” she said bravely. “We both come from small families, we might only ever have Frances. If God is not kind to us and we never have a son to carry your name, then all that will be left of the Tradescants is their name on their trees. These are your posterity, John – will you leave them to be named for another man, or grown by him? Or worse, neglected and felled by him?”

He looked down at her. “You are my conscience and my heart,” he said softly. “Are you telling me that we should garden for the king – even such a king as this – because if we do not then I lose my bond to my father and my rights to his name, and my claim to history?”

She nodded. “I wish it were an easier road to see,” she said. “But surely you can plant the king’s garden and take the king’s gold without compromising your soul or your conscience. You don’t need to be his man, as your father was wedded to Cecil and then to Buckingham. You can just take his wage and do his work. You can be an independent man working for pay.”

J hesitated for one more moment. “I wanted to be free of all this.”

“I know,” she said lovingly. “But we have to wait for the right time. Who knows, there may come a time when the whole country wants to be free of him? Then you will see your course. But until then, J, you have to live. We have to eat. We have to live with your father and mother and keep the Ark afloat.”

Finally he nodded. “I’ll tell him.”

J did not speak to his father till dinnertime the following day when the family was gathered together again, Frances beside her mother, John at one end of the big dark wood table and J at the other, Elizabeth seated between her husband and son.

“I have been considering. I will work with you at Oatlands Palace,” J announced abruptly.

John looked up, swiftly concealing his surprise. “I’m glad to hear it,” he said, keeping the joy from his voice. “I shall need your skills.”

Elizabeth and Jane exchanged one swift, relieved glance. “Who will run the business here while we are away?” J asked, matter-of-fact.

“We will,” Elizabeth said, smiling. “Jane and I.”

“Frances too,” Frances said firmly.

“And Frances, of course. Peter will show people round the rarities, he does it beautifully now, like a barker in a fairground; and you will be home often, one of you would be home for a day or two, surely?”

“When the court moves on from Oatlands we will be able to do as we please,” John said. “They will want beauty when they visit; we can do half of that with plants grown here in the seed beds and set in at the right time. When they are not at Oatlands we can go about our business here.”

“I will not hear heresy,” J warned.

“I myself shall guard your tender conscience,” his father assured him.

Reluctantly J chuckled. “Aye, you can laugh, but I mean this, Father. I will not hear heresy, and I will not bow down low to her.”

“You will have to uncover your head and bow,” John told him firmly. “That’s common politeness.”

“The Quakers don’t,” Jane volunteered.

John gave her a swift sideways look under his brows. “I thank you, Mistress Jane. I know the Quakers don’t. But J is not a Quaker-” he glared at his son as if to dare him to confess yet another step down the road to a more and more radical faith “ – and the Quakers do not work for me in the king’s garden.”

“They are still his subjects,” she said staunchly.

“And I honor their faith. Just as J is the king’s subject and has a right to his conscience, inside the law. But he will be obedient and he will be courteous.”

“And what shall we do if the law changes?” Elizabeth asked. “This is a king who is changing the shape of the church itself, whose father changed the Bible itself. What if he changes yet more and makes us outlaws in our own church?”

J glanced at his mother. “That’s the very question,” he said. “I can bend for the moment, but what if matters get worse?”

“Practice before principle,” John said with Cecil’s old remembered wisdom. “We’ll worry about that if it happens. In the meantime we have a road we can all take together. We can obey the king and dig his wife’s garden, and keep our consciences to ourselves.”

“I will not listen to heresy and I will not bow down low to the papist queen,” J stated. “But I can be courteous to her and I can work for my father. Two wages coming in is better than one. And besides-” He glanced up at his father with a silent appeal. “I want to do my duty by you, Father. I want there always to be a Tradescant at Lambeth. I want things working right in their right places. It’s because the king does not work right in his right place that everything is so disturbed. I want order – just as you do.”

John smiled his warm loving smile at his son. “I shall make a Cecil of you yet,” he said gently. “Let us put some order in the queen’s garden and keep the steady order of our own lives, and pray that the king does his duty as we do ours.”

The queen had commanded that John should have lodgings in the park at Oatlands and that everything should be done as he wished. His house adjoined the silkworm house and was warmed by the sun all day and by the charcoal burners which were set about the walls of the silkworm house all night. John at first found the thought of his neighbors the maggots, silently munching their way through mulberry leaves night and day, immensely distasteful; but the house itself was a miracle of prettiness, a little turreted play-castle of wood, south-facing with mullioned windows and furnished by the order of the queen with pretty light tables, chairs and a bed.

He was to eat in the great hall with the other members of the household. The king demanded that dinner be served in the great hall in full state whether he was there or not. The ritual demanded that a cover be set on the table before his chair, that dishes be put before the empty throne and that every man should bow to the throne before entering the hall and on leaving it.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу