Whether or not trivial, the incident with Lisette troubled me during subsequent weeks.Would I have risked joining the July Plot, joining Stauffenberg in placing the bomb beneath the Führer’s table? Only had Wilfrid ordered it, and a Wilfrid never gives orders. What else had I inherited from Mother? Timidity.

After too much wine, to test my courage, I attempted to stab my hand but only damaged a table of some value, an action noticed by Marc-Henri. In unwonted verbiage he referred to it as Existentialist Absurdity, Wilfrid annoying me by a nod of agreement.

When a dinner guest mentioned Aktion Sühnezeichen , young German Christians spending vacations in expiating German guilt in helping in bomb-devastated cities, I professed indifference with only a tinge of insincerity. I was not Christian, I had renounced Germanhood, I had nothing to expiate.

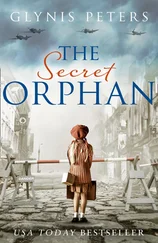

England remained more attractive than a Fourth Reich or the communist-policed East. Thousands had wept, sung English songs, cheered, when a red London bus toured wretched Europe as symbol of normality restored. Today, in cafés and cabarets, I was provoked by hearing the English, unforgiven for deserting France in 1940, ridiculed as philistine, pretentious, hypocritical.

English cousins might await me, antique doors wide open, on their tough island, with its northern stoicism, farmyard humour, its writers, its stiff gentlemen so easily parodied, less easily embarrassed or outwitted. A people immune to the rhetoric that had convulsed Italy, rotted much of France, destroyed Germany.

Wilfrid easily scented my preoccupations. ‘I have heard, though it may be untrue – history too often being at the mercy of literary men and a number of women – that, defeated in France, London under bombs, your Mr Churchill ordered the construction of landing craft, for eventual return to Europe. Some of his more intellectual colleagues, we hear, were ready to accept Hitler’s word and ponder his peace terms. Hitler’s word!’ He himself pondered. ‘Churchill, so often mistaken, his detractors not invariably right.’

That ‘your’, though unemphatic, was unpleasantly distinct, perhaps prelude to my dismissal to England.Yet it also recalled a day surely unsullied by the ulterior and suspect. We had visited a quiet mansion at Saint-Germain-en-Laye, once residence of an exiled English king.We lazed by a pool canopied by willows, gold-fish flicking between broad white lilies. As if from nothing, Wilfrid murmured, ‘Looking-glass Wonderland’. This, though in keeping with his ruminative mood, yet also chimed from far beyond this heightened pastoral afternoon, into my own dreaminess. Goal posts melted to lilies, tank-like dowagers transformed to redcoats and white smoke, dukes and committees coalesced into dense puddings under Sherlock’s terrible lens. Vast club armchairs and leathery books metamorphosed into pallid cliffs and lawnmowers, and I saw my grandmother as a shy girl watching from behind a fan the caustic old Queen.

Unaware of my self-satisfying visions, Wilfrid, beaky, like some allegorical bird in a missal, resumed the everyday, again rousing my very faint disquiet. ‘You might be respectfully astonished by their public schools, a misnomer, like so much in England. Quite possibly it was in this very garden of delights that Talleyrand declared that the best schools in the world were English public schools, and that they were dreadful.’

The thought of Lisette made that afternoon no longer innocuous, as though a calm, classical face abruptly showed in ugly profile.

Meanwhile, Paris itself was restless. Summer greens and golds, delicate morning haze, resplendent sunsets, children’s cries were unchanged, but political cat-calls had restarted. After a respite from denouncing Marshall Aid, Dollar Imperialism, the Bomb, and applauding Soviet support for small nations, the Left and Right were excited by a new movie, compendium of newsreels illustrating Jünger’s Diary of a German Officer , memoirs of Occupied Paris, in which French personalities famed and loved – Chevalier, Borotra, Arletty, Guitry, Luchaire – shining, complacent, were seen at a lavish Nazi reception, toadying to Ambassador Abetz. Riots rocked the cinema and spread throughout Paris, Lyons, Marseilles. Three bodies, dead, handcuffed together, were discovered at Saint-Cloud, a Jewish cemetery was desecrated, Vive le Maréchal stridently painted on the Column. Debonair Hotel Meurice, former Wehrmacht HQ, was picketed, and a lorry tipped a mass of dung on to rue de Saussies, beneath which had been Gestapo torture cells. A famous woman couturier was pushed from a balcony, almost fatally. Germany’s most celebrated operatic Isolde, interviewed on Radio Paris, was both hysterically applauded and attacked when, asked why she so zealously performed for the Führer’s court, replied with disdainful incredulity, ‘You should know that the artist is above society.’ The Left suffered minor reverse when Brother Jean-Luc, long-established Resistance martyr, was exposed as having been transported to Treblinka for seducing boys, 1943.

‘Good!’ Marc-Henri was at last stirred. ‘Very good.’

I now noticed, for the first time, that, eating in public places, Wilfrid always sat facing the door and street. It gave me a Draufgängertum , a creepy delight in danger.

Bastille Day was frenzied as always. On walls, pavements, vehicles, plinths, appeared stickers of a cross within a circle, insignia of an illegal anti-Arabic military cabal, whose plastic bombs had already shattered a street, blinding five children and killing three teachers outside a lycée. On boulevard de la Chapelle, I had to dodge a fight between rival pieds noir . That evening, attempting to wrest poetry from the infinite, I watched fireworks over Versailles, sapphires splintering, fiery diamonds encircling the zodiac, my verbal shots dead on reaching paper.

No poet, I was enveloped in a story, the plot not yet discernable and with either too many themes or none.

More urgent than bombs and Algerians, my body was protesting against sexual frustration. I was reluctant to consult Wilfrid, though I assumed he could have recommended a select maison . I could only dawdle on streets with the need but no courage to follow the inviting glance or ambiguous nod.

Could Wilfrid once have encountered some Medusa or luscious Ganymede, then covering wounds with irony and flippancy, while secreting passions he refused to fulfil? Once he made as if to touch my arm, then sharply desisted, as if remembering a dangerous current. Such restraint made the Herr General boisterous, almost ragtime, in his affections.

Our home was urbane, luxuriant, but chaste, and despite his multifarious acquaintances, Wilfrid seemed without intimacies. Lisette and Marc-Henri might know more but could scarcely be cross-examined. In contrast was his pleasure at the welcome always received from children. ‘Wilfrid’s come!’ He handled them, deftly, amiably, as he had done with everyone at Meinnenberg, once defusing a suspicious ten-year-old by enquiring whether he was still at school.With children, I myself was only ‘le Herr’.With them, as with animals, even flowers, he was gravely considerate, without flattery or condescension, aware of their desires for reassurance and equality.

I was embarrassed when he saw me, like Marc-Henri, before a mirror.

‘Your looks, Erich, could procure you at least a petit Trianon.’

My looks! Manifestly devoid of sexual appeal, eyes blue-green and humourless, face too northern, raw, high-boned, squarish under light hair. Under French scrutiny, I could have modelled for a Hitler Youth leader.

He often used words as though, for real communication, they were second best. His Bodhisattva suggested a religious temperament, his manner a lack of formal beliefs. His bedroom, very austere, had many books, including Homer and Lucretius, the Bible, Koran, Rig-Veda, Upanishads, the Tao Te Ching, alongside works by Albert Schweitzer, Romain Rolland, Fridtjof Nansen, Jean Jaurès, mighty humanists.We disputed over a Taoist text: The Sage sees everything without looking, accomplishes everything without doing .

Читать дальше