‘I mean, come on, Pop,’ Wolfgang went on. ‘Really, why do you care? You’re not religious. When did you last even go to a synagogue?’

‘We do things because we do them,’ Herr Tauber said angrily, while the rabbi continued to nod sagely at every remark while accepting a refill of his schnapps from Wolfgang. ‘Just like the Orthodox Greek fellow with his smoking incense or the Catholic with his wafer, which he knows very well isn’t a piece of Christ’s flesh. These things are done. That’s reason enough. It binds a person to his own past. It honours our elders and keeps us steady. Tradition is what has made Germany great.’

Wolfgang snorted once more.

‘Germany isn’t great, Konstantin,’ Wolfgang said, knowing full well that his father-in-law hated him to address him by his first name, preferring either ‘Herr Tauber’ or ‘Papa’. ‘Germany is a basket case. Germany is crippled, bankrupt, starving and insane. If Germany was a dog, you’d put a bullet in its head.’

Konstantin Tauber flinched. Despite having been well over forty in 1914, he had served with distinction in the Great War, winning an Iron Cross which he wore always on his uniform and in civilian clothes on the slightest excuse.

‘Germany was great,’ he said angrily, ‘and it will be great again despite the best efforts of you and your leftist friends.’

‘Wolfgang’s not a leftist, Papa,’ Frieda said, ‘he just likes jazz.’

‘It’s the same thing,’ Tauber replied, ‘and only a leftist would deny his sons their cultural birthright.’

‘What? To have their pricks interfered with?’ Wolfgang enquired. ‘Some birthright!’

‘Can you please moderate your language in front of my daughter and the rabbi!’ Herr Tauber thundered back.

‘This is my home and I’ll say what I like, mate!’

‘Look!’ Frieda snapped. ‘I have just given birth to twins. There isn’t any water. There isn’t any heat. There isn’t any light and there isn’t any food. Can we please leave the question of the boys’ foreskins to another day?’

The rabbi shook his head sadly.

‘Another day is not possible, Frau Stengel,’ he said, ‘for this is the eighth day and circumcision must be proffered on no day but this unless the child’s health is at risk, as it is written.’

‘Their health is at risk,’ Frieda protested. ‘There’s no water in the taps.’

‘For three thousand years we did without taps,’ Rabbi Jakobovitz replied, ‘just as we did without heat and electric light. I’m afraid that it’s now or not at all, my dear.’

‘Then it’s not at all,’ Frieda said firmly, ‘because we’re not doing it until they turn the water on.’

‘In that case,’ Jakobovitz said, seeming to perk up somewhat, ‘since a steady hand is no longer required, perhaps, Herr Stengel, I might trouble you for another schnapps?’

Wolfgang looked ruefully at his half-empty bottle, but hospitality was one tradition he did subscribe to.

Eventually the rabbi and Herr Tauber took their leave and, as the sound of their stumbling progress down the stairs faded away, Frieda and Wolfgang looked at each other. They were smiling but also serious; they both knew what the other was thinking.

‘Perhaps now was the time,’ Frieda said, ‘perhaps we should have said.’

‘I wanted to tell the old bastard, I really did,’ Wolfgang replied, ‘when he was banging on about tradition and birthright I was itching to tell him that one of his grandsons’ traditions and birthright were Catholic and Communist.’

‘Actually, I’m glad you didn’t,’ Frieda said.

‘I couldn’t find the moment.’

‘I know. It’s difficult. I think we’ve already left it too late.’

Wolfgang and Frieda had never meant the adoption to be a secret. They had fully intended to tell everybody immediately, both friends and relations. They were not ashamed, they were proud, proud of what they had done and proud of their son. Of both their sons.

But somehow they had missed the moment.

‘Why should anybody be bothered about it anyway?’ Frieda said. ‘It isn’t an issue for us, we don’t even think about it.’

‘No, I thought I would,’ Wolfgang agreed, ‘but I don’t.’

‘The funny thing is it feels to me as if it never really happened anyway. That the little bundle they took away was just a part of the process, just the boys messing about a bit, that’s all. There were two of them, then one disappeared for a moment and then he came back. Three little souls just became two.’

Together they looked at the sleeping boys, swaddled tight, side by side in a single cot.

‘I don’t want there ever to be any distance between them,’ Frieda continued, ‘or between them and us. We’re a family and by going into how we became a family it feels as though we’re saying it’s important when it isn’t. Why should anyone ever know? Why would anyone ever be interested?’

‘Well, it’s in the records at the hospital,’ Wolfgang said.

‘And as far as I’m concerned it can stay there,’ said Frieda. ‘It has absolutely nothing to do with anybody but us.’

A Whimper and a Scream

Berlin, 1920

THE KAPP PUTSCH, as it came to be known, lasted less than a week. While Berlin shivered in the cold and stood in line at standpipes for a trickle of icy water, Kapp, the would-be dictator, spent a lonely five days shuffling about the President’s Palace, staring forlornly out over the Wilhelmplatz, wondering how to bend the nation to his unalterable will. Eventually he decided that he couldn’t and instead took a taxi to Tempelhof airport and got on a plane to Sweden, never to be a head of state again.

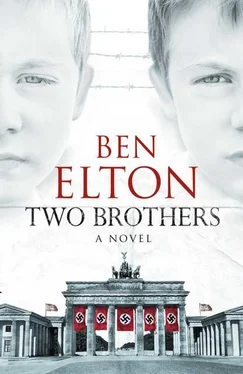

Berlin was jubilant and hundreds of thousands gathered on Unter Den Linden to watch as Kapp’s Freikorps troops marched out under the Brandenburg Gate through which they had strutted in triumph less than a week earlier.

Frieda and Wolfgang decided to join the celebration.

‘This is a big day for Berlin,’ Frieda said excitedly as they worked their way into the crowd, pushing the pram before them. ‘It’s not often that a bit of union solidarity gets the better of an army. Solidarity, that’s all you need.’

‘All I need,’ Wolfgang replied, seeing a stall selling beer and fried potatoes, ‘is a drink. This is a party after all.’

There was indeed a carnival atmosphere in the crowd. Hawkers were out in force and there were numerous street musicians busking for pfennigs. But as the retreating army could be heard approaching, the mood of the crowd began to change, turning sullen and angry as Charlottenburger Chaussee and Unter Den Linden rang to the harsh crash of thousands of hobnail boots smashing in deadly unison on the stone flags.

‘Shit,’ Wolfgang whispered nervously, ‘this has got to be the first time German soldiers have paraded through the Brandenburg Gate to complete silence.’

‘These aren’t soldiers,’ Frieda replied, ‘these are just crazy thugs.’

‘Well, I don’t like it,’ Wolfgang muttered nervously. ‘It’s weird.’

‘Too late now,’ Frieda observed.

So they stood with their pram as the hated columns marched past them and on through the great stone columns of Friedrich Wilhelm’s famous gate. Ragged-looking men with bitter angry faces. Soldiers still, despite what Frieda said, in old army uniforms and coal-scuttle steel helmets.

‘What’s that funny crooked cross,’ Wolfgang hissed, ‘painted on some of their helmets?’

‘I don’t know,’ Frieda said. ‘Actually, I think it’s Indian.’

‘ Indian? ’ Despite the strange solemnity of the occasion, Wolfgang almost laughed.

‘Yes, Buddhist or Hindu. I’m not sure which. I think it’s called a swastika.’

Читать дальше