I looked at him incredulously. “Wow, that’s very impressive.”

Right then the plump, fortyish waitress came to take our orders. Alex Luce asked in Chinese for the minced beef with tofu, and I, soy sauce chicken.

After her generous bottom waddled away, I asked, “Alex, you mind if I ask you a blunt question?”

“Of course not.” He poured tea first into my cup and then into his, showing good etiquette.

“All right, then. Why did you invite me to dinner?” Before he could respond, I went on, “If you’re lonely and want some company, I’m not the right person for you. Anyway, how old are you and where’re your parents?”

He laughed. “Oh, Lily, I’m twenty-one, not a child. Besides, my parents give me lots of freedom. They were divorced when I was six. I’m used to doing things by myself.”

“I’m sorry.”

He stared at me with expressive eyes. “Hmm… Lily, may I also ask why you travel alone?”

“I’m afraid that’s my own business.”

“Sorry. I don’t mean to pry.”

Feeling guilty, I patted his hand. “It’s OK. Sorry if I sounded rude.”

The waitress brought the kid his minced beef and set it down on the table with a loud thud. Then she cast me an “old Chinese horny with young American honey” look and dragged her wide posterior away.

Seeing Alex didn’t dig right into his plate, I asked, “Why don’t you start?”

“Your dish hasn’t come yet.”

So he was waiting for me. His good manners showed he must come from a good family.

“Go ahead, please, otherwise it’ll get cold.”

“I’ll wait,” he said.

A real stubborn kid.

Then the waitress brought my food. After she left, I noticed Alex even waited for me to dig into my food before he started. I was quite impressed. After all, he was so young and this was a cheap restaurant in China, not a gourmet one in Manhattan. The way he ate with such relish also pleased me. I liked people who loved and treasured their food, whether ordinary or gourmet. We ate and chatted while clicking chopsticks, smacking lips, sipping tea. He looked happy. My mind was occupied with too many things to feel anything.

Just as I was thinking how to get rid of him soon, he said, “Lily.”

“Yes?” I was sucking a succulent chicken bone.

“What is your itinerary?”

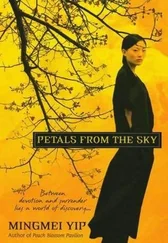

“Today the warriors, tomorrow the Huaqing Pool, then Dunhuang, Urumqi, the Mountains of Heaven, Taklamakan Desert, Turpan, something like that.”

“Wow, that’s where I’ll be going, too!” He looked excited, then asked shyly, “Maybe we can travel together?”

I almost swallowed my chicken bone whole. To calm myself, I gulped down a big mouthful of tea.

“Awww….” I choked myself on the scalding liquid.

“Are you OK?” His eyes and voice were filled with concern.

I nodded.

The last thing I wanted on this trip was to have company, let alone a kid whom I might even have to take care of. At twenty-nine, I had no wish to mother anybody.

But his declaration surprised me. “Please, let me… travel with you so I can watch out for things.”

I tried very hard not to laugh. The waitress, now standing in the corner, cast me another hateful look as if saying, “Now young American horny wants to get cozy with old Chinese honey.”

“Lily, you will be safer with me. I’ve been studying the grasshopper-style kung fu for many years.”

The thought of this young American pitting himself against Chinese hooligans practiced in martial arts amused me. I put down my chopsticks. “Alex, thank you, but sorry, I’d rather be alone.”

“But I am concerned about you.”

“About what?!” This time I almost spilled my tea.

“About you traveling by yourself along the Silk Road.” He nodded discreetly toward a group of men busy stuffing themselves at a nearby table. “See those men over there? I bet they’d cheat, rob, and even murder. And they’re everywhere.”

“Look, Alex, I appreciate your concern and your earlier help. But I hardly know you, and I will be quite OK on my own, thanks. So I think our first dinner together should be our last.”

Having said that, I raised a hand to signal the waitress for the bill.

Back at the hotel, I kept thinking about the strange kid. Who was he, and what did he want? Then I thought of my aunt. What did she want?

Under the hotel room’s dim light, I took out the tiny piece of clay I had chipped from the terracotta warrior and studied it. Why would this grain of clay be of any importance to anyone? Even if it really was a fake? Knowing I wouldn’t get an answer until I finished my journey, I wrapped it up in a tissue, put it in an envelope, and labeled it Xian with today’s date. Still jet-lagged I wanted to settle into bed, but I focused my energy on writing down today’s happenings in my journal, including the meeting with Alex Luce. After that, I flipped through my aunt’s instructions and planned my excursion for tomorrow—to visit the Beilin Museum to see the famous Beilin , Stele Forest, a field full of stone slabs on which were inscribed famous Chinese words of wisdom.

Mindy Madison, my aunt, had visited this Stele Forest and was particularly interested in the Classic of Filial Piety, an ancient text much admired throughout Chinese history. The Chinese say yinshui siyuan: “When drinking water, always remember where it comes from.” As children, we are supposed to be grateful for our parents, who gave us shelter, food, love, education—our very lives.

Why would my aunt want me to study this particular stele?

The next morning, still feeling uneasy from the previous day’s events—the warrior “accident” and the Alex Luce incident—I decided first to unwind by visiting the famous imperial bath, the Huaqing Pool. I threw on a T-shirt, blue jeans, and running shoes, gulped down a bowl of congee in the hotel coffee shop, then asked a bellman to call me a taxi.

Outside the hotel, despite the pollution, the sky was clear and blue, with a few wisps of decorative clouds playing hide-and-seek. During the long ride out from the city, there was not much to see except bicycles, pedicabs, handcarts, and the ubiquitous exhaust-spewing trucks. A few poplars stood forlornly by the road as we passed several old brick-and-tile houses and a rusting crane beside the skeleton of a half-constructed low building.

Finally the taxi pulled to a stop. I’d arrived at the foothills of Mount Li, where the famous Huaqing Hot Springs was located. Now feeling gritty and sweaty, I desperately craved a bath—private or public.

I paid a few renminbi and entered the reconstructed palacelike complex. I soon relaxed as I strolled by ponds with lotuses floating over carp swaying their tails lazily among weeds. As I took out my camera, a statue in the middle of a lake caught my attention. A plaque informed me that this was Yang Guifei in the Nine-Dragon Lake. This most famous of imperial concubines had bathed in the Huaqing Pool with Emperor Tang Xuanzong on many moonlit evenings a thousand years ago. Although the statue was crudely rendered, the story behind it was moving.

Among all the three thousand exquisite, flirtatious concubines in the inner palace, Emperor Xuanzong loved only one—Concubine Yang. Her beauty was reputed to be so stunning that it shamed the moon and mortified the flowers. In the following centuries, Yang was the muse of numerous poets and painters.

However, as the emperor became more and more infatuated with Yang, he also cared less and less about state affairs, until the mighty general An Lushan started a rebellion.

Pursued by An Lushan, Emperor Xuanzong fled southward with his palace guards, imperial soldiers, and a disguised Concubine Yang. Later, when the soldiers learned that Yang was among them, they refused to move forward, demanding she be put to death. They believed that Yang’s beauty and the emperor’s intemperate love caused the empire’s collapse. After a long and heated argument with his troops, the emperor realized, heartbreakingly, he had to acquiesce. And so, in the Buddha Hall under the moon—the same moon that had witnessed their sleepless nights of passion—the emperor ordered the only woman he loved to be hanged.

Читать дальше