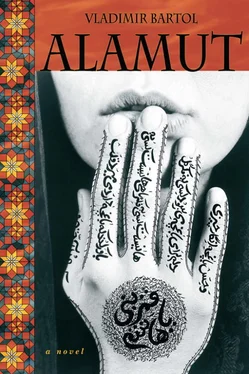

Vladimir Bartol - Alamut

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Vladimir Bartol - Alamut» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: Berkeley, Год выпуска: 2012, ISBN: 2012, Издательство: North Atlantic Books, Жанр: Историческая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Alamut

- Автор:

- Издательство:North Atlantic Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- Город:Berkeley

- ISBN:9781583946954

- Рейтинг книги:2.8 / 5. Голосов: 5

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Alamut: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Alamut»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Alamut — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Alamut», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Any of these readings is possible. But all of them miss the obvious, fundamental fact that Alamut is a work of literature, and that as such its chief job is not to convey facts and arguments in a linear way but to do what only literature can do: provide attentive readers, in a tapestry as complex and ambiguous as life itself, with the means of discovering deeper and more universal truths about humanity, about how we conceive of ourselves and the world, and how our conceptions shape the world around us—essentially, to know ourselves. Bartol does not overtly intervene in the narrative to guide our understanding of it in the way he wants. Instead, he sets his scenes with subtle clues and more than a few false decoys—much the way real life does—and then leaves it to us sort out truth from delusion. The most blinkered reading of Alamut might reinforce some stereotypical notions of the Middle East as the exclusive home of fanatics and unquestioning fundamentalists. (What, then, to make of the armies of black-shirted and leather-jacketed thugs that Europe spawned just sixty years ago?) A really perverted reading might actually find in it an apology for terrorism. That risk is there. But careful readers should come away from Alamut with something very different.

First and foremost, Alamut offers a thorough deconstruction of ideology—extending to all dogmatic ideologies that defy common sense and promise the kingdom of God in exchange for one’s life or one’s freedom to judge and make choices. Of course, there are Hasan’s long, enlightened diatribes against Islamic doctrine and the religious alternatives to it, which he organizes around the retelling of his own life experience, his search for truth as a young man, and his successive disillusionments. He tells of how he transcended his personal crisis by devoting himself exclusively to experience, science, and what can be perceived by the senses. But this positivism develops into a hyper-rationalism that, by excluding the emotional aspects of human experience as irrational and invalid, itself becomes dogmatic. At its extreme, Hasan’s rationalism proclaims the absence of absolute moral restraints, the supremacy of power as the ruling force of the world, and the imperative of manipulating lesser human beings to achieve maximum power and further his own ends—formally articulated in his sect’s supreme maxim: “Nothing is true, everything is permitted.”

Yet Bartol lets us see more of the complexities and weaknesses of this character than Hasan himself would probably admit to. We are given momentary glimpses of his visceral hatred for his lifelong rival, Nizam al-Mulk, who figures in the novel as his primary nemesis and object of revenge. Twice we see his terror at suddenly feeling alone and vulnerable in the universe. Near the novel’s climax, he makes the contradictory revelation that his life’s greatest driving force has been a fierce hatred of his country’s Seljuk overlords. And repeatedly, wordlessly, but unmistakably we see him reject opportunities for emotional and physical connectedness, even though deep down he just as unmistakably wants them. All of these irrational impulses threaten his rationalist ideology and so have to be suppressed, but in suppressing them Hasan obliterates facets of his personality. The result is an emotionally deformed, if intellectually brilliant human being—who is all the more tragic for the great power that he wields.

Throughout the last half of the novel, Hasan refers to each of various interconnected events that he has engineered as “the next act of our tragedy,” and it seems unclear just whose tragedy he is referring to. In the book’s final chapter, as Hasan looks ahead to the future, he refers to “those of us who hold in our hands the threads of this mechanism,” meaning the fearful mechanism of the sect of assassins. Aside from conjuring the image of Hasan as master puppeteer (which he is), these figurative threads and mechanisms also reverberate with the pulley- and rope-operated lift that his eunuch servants regularly use to hoist him up to his tower chambers. Considering that Hasan is also shown feeling vulnerable in that rudimentary lift, wondering what would happen if the eunuchs suddenly became aware of their degraded state and decided to cut the rope and send him crashing to his death, this final image of Hasan as master ideologue and manipulator becomes a highly ambiguous one. His apotheosis in the book’s last sentences, as he is hoisted up to his tower, where he will spend the rest of his life codifying Ismaili law and dogma, never again to emerge, is the ultimate ironic ending. What Hasan’s character doesn’t fully realize is that, in dispatching himself to the ultimate extreme of rationality, by willingly separating himself from human society in the name of this rationality, and by submitting himself to the “threads” of his own “mechanism,” he makes himself the tragedy’s most prominent victim.

So many of the novel’s emotional sparks are generated not discursively through narration or dialogue, which is dominated by reason, but in the unspoken, subtle interstices of the spoken exchanges between some of the main characters. It is the fleeting, sometimes apparently throw-away depictions of their emotional affect—involuntary facial expressions, glances, blushes, body language, suppressed wellings-up of emotion—that express far more of the truth of their being than their words can do. These affective communications are generally left incomplete, partly because they represent ineffable moments, and partly because supposedly higher circumstances (ideology in the case of the fedayeen; duty in the case of the girls; “reason” in the case of Hasan) invariably manage to crush them before they can fully express themselves. Yet they are some of the novel’s most pronounced and revelatory moments of truth.

The personalist philosophers who were so influential between the World Wars would have seen these highly charged moments of honesty and vulnerability in human relationships as the primary medium in which the divine force manifests itself. In reaction to dogmatic religion and similarly reductive tendencies in the social sciences (at that time, notably, Freudian psychology and Marxism), personalism granted equal importance to a wide range of facets in the human personality, from the biological, social and historical to the psychological, ethical and spiritual. Bartol studied in Paris at the same time as a number of his young countrymen who would later become influential personalist intellectuals, including the psychologist Anton Trstenjak and the poet Edvard Kocbek. Although Freud and Nietzsche are most frequently mentioned as early influences on Bartol—and certainly Hasan embodies their lessons to perfection—the importance that Alamut ultimately places on the development of the integrated human being suggests that if any ideology still counted for Bartol, it must have been something akin to personalism.

In this light, the book’s dual mottos, apparently in conflict with each other and the source of a fair amount of frustration for commentators over the years, begin to make sense. If “Nothing is true, everything is permitted” stands as a symbol of the license granted to the Ismaili elite, then the unrelated subsidiary motto “Omnia in numero et mensura” acquires an ultimately cautionary significance. All things within measure, nothing too much. In other words, skepticism and rationality are important assets, but overdependence on them at the expense of compassion leads to the tragedy that engulfs Hasan as much as it does his witting and unwitting victims.

Bartol incorporated many of his own qualities and personal interests into his portraits of Hasan and the novel’s other characters. He was an avid student of philosophy, history, mathematics, and the natural sciences. He was an amateur entomologist and (like another Vladimir, four years his senior and the author of a book called Lolita ) an avid lepidopterist. In a country of mountain climbers, Bartol literally climbed with the very best of them. Like a famous French writer three years his senior, he was an enthusiastic and skilled small aircraft pilot—and all of this just as a prelude to his career as a writer. An individual who is that inquisitive and that eager for experience is either driven and obsessed, or in love with life. In his private life, Bartol was an example of the latter personality type, but in his novel he chose to portray an extreme version of the former.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Alamut»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Alamut» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Alamut» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.