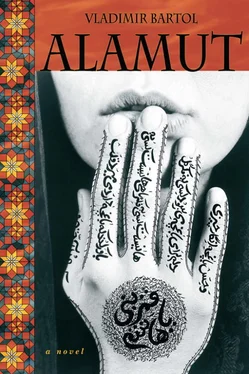

Vladimir Bartol - Alamut

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Vladimir Bartol - Alamut» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: Berkeley, Год выпуска: 2012, ISBN: 2012, Издательство: North Atlantic Books, Жанр: Историческая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Alamut

- Автор:

- Издательство:North Atlantic Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- Город:Berkeley

- ISBN:9781583946954

- Рейтинг книги:2.8 / 5. Голосов: 5

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Alamut: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Alamut»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Alamut — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Alamut», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

One of Bartol’s strengths in Alamut is his ability to virtually disappear as a perceptible agent of the novel and let his characters carry the story. There is no authorial voice passing judgment or instructing readers which characters to favor and which to condemn. In fact, readers may find their allegiances shifting in the course of the story, becoming confused and ambivalent. Bartol certainly intended to write an enigmatic book. Literary historians have looked to Bartol’s biography, personality and other work for keys to understanding Alamut , but much in the author’s life still remains hidden from view. Its very openness to a variety of interpretations is one of the things that continue to make Alamut a rewarding experience.

Perhaps the simplest way to approach Alamut is as a broadly historical if highly fictionalized account of eleventh-century Iran under Seljuk rule. A reader encountering the novel from this perspective can appreciate its scrupulously researched historical background, the general absence of historical anachronisms, its account of the origins of the Shiite-Sunni conflict within Islam, and its exposition of the deep-seated resentments that the indigenous peoples of this area have had against foreign occupiers, whether Muslim or non-Muslim, for over a millennium. The author’s gift for populating this setting with sympathetic, complex, and contemporary-seeming personalities, whose aspirations and fears resonate for the reader at a level that transcends the stock expectations of the exotic scenic décor, make this historically focused reading of the novel particularly lifelike and poignant.

A second reading of Alamut anchors its meaning firmly in Bartol’s own time between the two World Wars, seeing it as an allegorical representation of the rise of totalitarianism in early twentieth-century Europe. In this reading, Hasan ibn Sabbah, the hyper-rationalistic leader of the Ismaili sect, becomes a composite portrait of Mussolini, Hitler and Stalin. In fact, Bartol originally intended to dedicate the first edition of his book “To Benito Mussolini,” and when he was dissuaded from doing this, suggested a more generic dedication “To a certain dictator,” which was similarly vetoed. Either dedication would almost certainly have been a bold exercise in high irony, but his publisher rightly saw the risks involved at that volatile time: lost readership, irate authorities. Some of the characters appear to have been drawn from real-life models that dominated the newsreels at that time. Abu Ali, Hasan’s right-hand man, is depicted delivering inspiring oratory to the men of Alamut in a way reminiscent of no one so much as Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels. The ceremonial nighttime lighting of the castle of Alamut could pass for an allusion to the floodlit rallies and torchlight parades of the Nazi Party. The strict organizational hierarchies of the Ismailis, the broad similarities between some characters and their corresponding types within the Fascist or National Socialist constellations, and the central role of ideology as a sop for the masses all resonate with the social and power structures then existing in Germany, Italy and Soviet Russia, as do the progressively greater levels of knowledge and critical distance from ideology that are available to Hasan’s inner circle.

More recently, yet another interpretation tries to persuade us that Alamut is a roman-à-clef representation of what should have been the ideal Slovenian response to the German and Italian totalitarianism then threatening Slovenia and the rest of Europe—in other words, a mirror image of the Hasan-as-Hitler reading. This interpretation looks to Bartol’s origins in the area around Trieste, and his undisputed anger at Italian domination and persecution of the ethnic Slovenes in those regions beginning in the 1920s. Bartol was indeed a close personal friend of the head of a Slovenian terrorist group, the “Tigers,” whose members conducted violent attacks on Italian institutions and individuals in the Italian-Slovenian border regions. (The group’s Slovenian designation “TIGR” was actually an acronym based on the names of four key disputed areas: Trieste, Istria, Gorizia, and Rijeka [Italian Fiume].) When his friend was captured by the Italians in 1930 and sentenced to twenty years in prison, Bartol made a laconic and ominous note in his diary, “Zorko, I will avenge you.” Hasan’s positive traits—his rationality, intelligence and wit—together with his revelatory confession late in the novel to his youthful alter ego, ibn Tahir, that his entire life’s work has been dedicated to liberating the Pahlavi-speaking population of Iran from foreign domination, would all seem to support this view of the novel as an Aesopian exhortation to oppressed Slovenes, focused around celebrating the charismatic personality and Machiavellian brilliance of the liberation movement’s leader, Hasan/Zorko.

But as tempting as this Slovenian nationalist reading of Alamut may be, ultimately it rings facile and flat. For one, how can Hasan’s nationalism—for which Bartol anachronistically draws on an ideology arising centuries later, out of eighteenth-century European thought—square with Hasan’s far more exhaustively articulated nihilism, his rejection of all ideology, his acceptance of power as the ruling force of the universe, and his implacable pursuit of power for its own sake? Moreover, how could any self-respecting human being, Slovene or otherwise, take to heart a manifesto based on the cynical manipulation of human consciousness and human life in furtherance of the manipulator’s own goals? Attempts to make Alamut work as a veiled treatise on national liberation also run up against Bartol’s own paradoxical avowals of authorial indifference to politics. And ultimately they are reductive and self-contradictory, turning what reads and feels like a many-faceted work of literature rich with meaning into a two-dimensional ideological screed.

This brings us to the present day and the reading of Alamut that is bound to be particularly tempting, now that America has incurred Hasan-like blows from a nemesis to the east and delivered its own counterblows of incalculable destructive force in return. This reading will see Alamut , if not as a prophetic vision, then at least as an uncanny foreshadowing of the early twenty-first century’s fundamental conflict between a nimble, unpredictable upstart relying on a relatively small but close-woven network of self-sacrificing agents on the one hand, and a massive, lumbering empire on the other, put constantly on the defensive and very likely creating new recruits for its adversary with every poorly focused and politically motivated offensive step that it takes. The story of today’s conflict between al Qaeda and the West could be a palimpsest unwittingly obscuring the half-obliterated memory of a similar struggle from more than a thousand years ago: injured and humiliated common folk who prove susceptible to the call of a militant and avenging form of their religion; the manipulative radical ideology that promises its recruits an otherworldly reward in exchange for their making the ultimate sacrifice; the arrogant, self-satisfied occupying power whose chief goal is finding ways of extracting new profits from its possession; and the radical leader’s ominous prediction that someday “even princes on the far side of the world will live in fear” of his power. But however many parallels we may be able to find here between Bartol’s eleventh century and our twenty-first, there is nothing clairvoyant about them. Alamut offers no political solutions and no window on the future, other than the clarity of vision that a careful and empathetic rendering of history can provide. There is, admittedly, much for an American readership to learn from a book like Alamut , and better late than never: thanks to Bartol’s extensive and careful research, a rudimentary education in the historical complexities and continuities of Iraq and Iran, reaching back over a thousand years, is one of the novel’s useful by-products.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Alamut»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Alamut» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Alamut» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.