“Sir, I… come to beg you to confess all and swear allegiance to the king that he might show you mercy,” she said.

“Will he show mercy to my country? Will he take back his soldiers, and let us rule ourselves?” he asked her.

“Mercy… is to die quickly. Perhaps even live in the Tower!” Her eyes brimmed with tears and the illusion of hope. “In time, who knows what can happen if you can only live.”

“If I swear to him, then everything I am dead already,” Wallace said.

She wanted to plead, she wanted to scream. She couldn’t stop the tears. And the jailers were watching.

“Your people are lucky to have a princess so kind that she can grieve at the death of a stranger,” he said.

She almost went too far, she pulled closer to him—but she didn’t care. She whispered, pleaded, “You will die! It will be awful!”

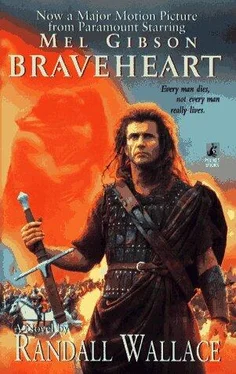

“Every man dies. Not every man really lives.”

Princess Isabella and William Wallace stared into each other’s eyes. Neither knew nor cared how long. Then she pulled out a hidden vial and whispered, “Drink this! It will dull your pain.”

“It will numb my wits, and I must have them all. If I’m senseless or if I wail, then Longshanks will have broken me.”

“I can’t bear the thought of your torture! Take it!”

She pressed the vial to his mouth and poured in the drug. She heard the jailers shifting outside the cell door, trying to see what she was doing; she backed up, still looking at William, her eyes wide, full of love and good-bye. Then she turned, and keeping her face lowered, as if she could hide her tears, she was gone.

Wallace watched her go. When the door clanged shut, he spit the purple drug onto the stone floor of his cell.

LONGSHANKS LAY HELPLESS, HIS BODY RACKED WITH consumption. Edward sat against the wall, watching him die, glee in his stare. The princess entered. She paused at the door and watched the old king’s chest rising and falling; when she looked up at his waxlike face, she saw that he was looking at her. “I have come… ,” she said, “to beg for the life of William Wallace.”

“You fancy him,” Edward said.

“I respect him. At worst he was a worthy enemy. Show mercy… oh thou great king…and win the respect of your own people.”

Longshanks’s body trembled; he was making a great effort—to speak? To lift his hand? His jaw worked and there was a gurgle from his throat, but no words came out. And then Isabella realized what the king intended: he was shaking his head.

“Even now, you are incapable of mercy?” she asked. But hatred still glowed in his eyes. The princess looked at her husband. “Nor you. To you that word is as unfamiliar as love.”

Edward relished what he now had to tell her. “Before he lost his powers of speech, my lord king told me his one comfort was that he would live to know Wallace was dead.”

Edward was smiling.

Isabella turned from him and moved to Longshanks’s bedside. She leaned down and grabbed the dying king by the hair. The guards flanking the door started forward but the princess’s eyes flared at them with more fire than even Longshanks once showed—and the guards backed off. She bent down and hissed to Longshanks, so softly that even Edward couldn’t hear, “You see? Death comes to us all. And it comes to William Wallace. But before death comes to you, know this: your blood dies with you. A child who is not of your line grows in my belly. Your son will not sit long on the throne. I swear it.”

She let go of the old king. He sagged like an empty sack back onto his satin pillows. Without even a look at her husband, she strode out of the room, with the rattling breath of the dying king rasping the air like a saw.

SMITHFIELD IS A SECTION OF LONDON LYING TWO MILES from Westminster Hall. In 1305 it was a place of butchery, where cattle were slaughtered and dismembered for the tables of the city dwellers. It was also the customary place of execution.

And so it was to Smithfield, on the twenty-third day of August of that year, that William Wallace was taken, strapped to a wooden litter and dragged by horses across the cobblestones. A crowd had filled the open, grassy square surrounded by the meat shops, and the people were in a festive mood. Hawkers sold roast chickens and beer from barrels, while street entertainers juggled and performed comic acrobatics in hopes of collecting halfpennies.

When the royal horsemen arrived dragging Wallace, the crowd fell silent. When they cut him loose and led him through the crowd, the people began to jeer and throw at him anything handy: chicken bones, rotten vegetables, rocks, empty tankards. Wallace did not react as the missles pelted off him. The bone rattling journey, bouncing across the cobblestones, may have stunned him already—or perhaps the pain of rocks thrown against his face seemed nothing to him compared to what he knew was to come.

Grim magistrates prodded Wallace, and he climbed the execution platform. On the platform were a noose, a dissection table with knives in plain view, and a chopping block with an enormous ax. Wallace did not look away from these implements of torture.

It was both to him and the crowd that the lord high magistrate announced, “We will use it all before this is over.” Then his dark eyes fixed Wallace’s. “Or fall to your knees now, declare yourself the king’s loyal subject, and beg his mercy, and you shall have it.”

He emphasized mercy by pointing to the ax.

Wallace was pale and trembled—but he shook his head.

The crowd grew noisier as they put the noose around Wallace’s neck.

The princess heard the distant clamor from her room in the palace, and she lowered her head in helpless agony.

Helpless too were Hamish and Stephen, wearing the hooded smocks of English peasants, among the onlookers in Smithfield Square. They had come to this terrible moment because the only thing worse than being there was to not be there while this was happening, and they stood hoping to catch William’s eye, as if in doing so they could somehow shoulder some of his pain.

Lying in his kingly bedchamber, Longshanks rattled and coughed blood, as Edward, the future king, waited for him to die.

Robert the Bruce paced along the walls of his castle in Scotland. His eyes were haunted; he looked south, toward London, and in his soul he heard the sounds of the horrible spectacle as clearly as if his own body had been pitched before the executioners.

All of them had become but observers of the event. All—the crowded heads, the nobles who contented for the thrones, the peasants, the priests, the acrobats, and the fools, even the lord high magistrate and his muscled assistants who were conducting the proceedings—were powerless and insignificant. And yet the man with his hands and feet manacled, his cheeks bloody, his heart pounding out the final rhythms of his life—he stood and faced his executioners as if the whole world turned on what he would—or would not—do now.

There on the platform, a trio of burly hooded executioners cinched a rope around Wallace’s neck and hoisted him up a pole.

“That’s it! Stretch him!” the crowd yelled.

The warrior who had fought alone and at the head of thousands, who had defeated great armies and sacked cities, who had struck terror in the world’s mightiest nation, now dangled at the end of a rope, his face turning purple, his eyes bulging, the veins popping at his neck where the noose bit into his skin. The people cheered their approval. They knew this was not the end; much more was intended. But as the moments ticked on and on, the Scot at the end of the rope looked less to them like an enemy and more like simple flesh and blood. They grew silent, wondering at how much he could take, at how much his tormentors would extend his agony, before they lessened the torture—lessened it, that it could be extended.

Читать дальше