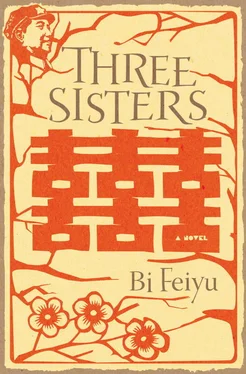

Bi Feiyu

THREE SISTERS

Translated from the Chinese by

Howard Goldblatt and Sylvia Li-chun Lin

Yumi

LITTLE EIGHT WAS barely a month old when Shi Guifang handed him over to her eldest daughter, Yumi. Outside of taking him to her breast several times a day, she showed no interest in her baby. In the normal course of events, a mother would treat her newborn son like a living treasure, cuddling him all day long. But not Shi Guifang. The effects of a monthlong lying-in had been the addition of some excess flab and a spirit of indolence. She seemed to sag, albeit contentedly; but mostly she displayed the sort of relaxed languor that comes with the successful completion of something important.

Shi Guifang savored the guiltless pleasure of leaning lazily against her door frame and nibbling on sunflower seeds. She’d pick a seed out of the palm of one hand, hold it between her thumb and index finger, and slowly bring it up to her mouth, her three remaining fleshy fingers curling under her chin. She demonstrated remarkable sloth, mainly in the way she stood, with one foot on the floor, the other resting on the doorsill. From time to time she switched feet.

People did not mind Shi Guifang’s indolence, but sometimes a lazy person will appear proud, and it was this that people found intolerable. What gave her the right to look so superior when all she did was crack sunflower seeds? She definitely was not the Shi Guifang of earlier days. People had once praised her as a woman who eschewed the usual prideful airs of an official’s wife. She smiled when she talked to them, and when eating made that impossible, she smiled with her eyes. But now, as people thought back over the past decade, they concluded that she had been putting up a front all that time. Embarrassed that she’d had seven girls in a row, she had suppressed her true nature with a show of excessive courtesy. That was then. Now the birth of a son, Little Eight, had given her the right to be haughty; she was as courteous as ever, but there’s courtesy and then there’s courtesy. Shi Guifang typified the amiable, approachable manner of a Party secretary. But her husband was the Party secretary, not she, so what right did Shi Guifang have to be so indolently amiable and approachable?

Second Aunt, who lived at the end of the alley, often came out to rake the grass that was drying in the sun. She sized up Shi Guifang with a sneer: She had to open her legs eight times before a son popped out , Second Aunt said to herself, and now she has the cheek to act like she’s a Party secretary.

Shi Guifang had come to Wang Family Village [1] Many rural villages are populated mainly by families with the same surname.

from Shi Family Bridge. During the twenty years she was married to Wang Lianfang she had presented him with seven girls, not counting three miscarriages. She was often heard to say that the three who didn’t make it had probably been boys, since all the signs had been different; even her taste buds had undergone a change. She spoke of her miscarriages as if they were missed opportunities; had she managed to keep just one of them, she’d have carried out her life’s mission.

On one of her trips to town she visited a clinic, where a bespectacled doctor confirmed her suspicions. His scientific explanation would have had the average person scratching his head in bewilderment. But Shi Guifang was smart enough to get the gist of it. Put simply, being pregnant with a boy demands more care, the pregnancy is harder to hold on to, and spotting is unavoidable, even when the woman manages to keep the baby. Shi Guifang sighed at the doctor’s sage words, reminding herself that a boy is a treasure, even in the womb. She was consoled to learn that fate was not keeping her from having a son, which was more or less what the doctor was really saying, and that she must have faith that science also plays a role. But this did little to lessen her feelings of despair. On her way home she stared for a long moment at a snot-nosed little boy on the pier before she tore her eyes away, dejected.

That was not, however, how Wang Lianfang saw things. Having studied dialectics in the county town, Party Secretary Wang knew all about the relationship between internal and external factors, and the difference between an egg and a rock. He had his own irrational understanding of boy and girl babies. To him, women were external factors, like farmland, temperature, and soil condition, while a man’s seed was the essential ingredient. Good seed produced boys; bad seed produced girls. Although he’d never admit it, when he looked at his seven daughters his self-esteem suffered.

A man with wounded self-esteem develops a stubborn streak. By initiating a battle with himself, Wang Lianfang resolved to overcome every obstacle on his way to ultimate victory. He vowed to have a son, if not this year, then the next. If not next year, then the year after; and if not the year after, then the year after that. Not in the least anxious that he might be denied a son to carry on the line, he settled in for a long, drawn-out battle rather than seek a speedy victory. Admittedly, depositing his seed in a woman was not all that difficult.

Shi Guifang, on the other hand, endured considerable dread. During the first few years of their marriage, she’d been fairly resistant to sex. On the eve of her wedding, her sister-in-law had put her lips close to Shi Guifang’s ear—she could feel her hot breath—to admonish her not to open too wide and to cover herself if she desired her husband’s respect and did not want to be thought wanton. In an enigmatic tone that hinted at a broad knowledge of human affairs, her sister-in-law had said, “Remember, Guifang, the harder the bone, the better it is to gnaw.” In fact, Guifang had no use for her sister-in-law’s wisdom. But after several girls in a row, the situation changed dramatically. No longer resistant, no longer coy, Guifang turned fearful. She clamped her legs together and covered herself with her hands. Inevitably, the clamping and covering began to rankle Wang Lianfang, who one night slapped her twice—once forehand and once backhand.

“Who do you think you are?” he had said, angrily. “Not a single boy has popped out of you, and yet you still expect two bowls of rice at every meal.”

Anyone standing beneath the window would have heard every word, and if it got around that she wouldn’t do it, she’d have been ruined. Only an ugly shrew would refuse to do it if all she could manage was girls.

A slap now and then didn’t bother Guifang, but Wang’s shouts made her go limp. When that happened, she could no longer clamp her legs shut or cover herself. Like a clumsy barefoot doctor, Wang would set his jaw as he pulled down her pants and, seconds after entering her, spray his seed into her body. That is what really frightened her, his seed, since every one of those little invaders was capable of turning into a baby girl.

Finally, in 1971, the heavens smiled on them. Shortly after the Lunar New Year, Little Eight was born. It was not a run-of-the-mill Lunar New Year, for the people had been told to turn the celebration into a revolutionary Spring Festival. Firecrackers and games of poker were banned throughout the village, an edict that Wang himself announced over the PA system, though even he was not altogether sure just what a “revolutionary” holiday ought to be. But that did not matter so long as someone in the leadership had the courage to make the announcement; new policy always emerged from the mouth of a member of the leadership. Standing in his living room, Wang held a microphone in one hand and fiddled with the switches on the PA system with the other. Neatly lined up in a row, the little switches were hard, shiny exclamation marks.

Читать дальше