Samuel Gardiner - A Student's History of England, v. 1 - B.C. 55-A.D. 1509

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Samuel Gardiner - A Student's History of England, v. 1 - B.C. 55-A.D. 1509» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Издательство: Иностранный паблик, Жанр: foreign_prose, История, foreign_antique, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Student's History of England, v. 1: B.C. 55-A.D. 1509

- Автор:

- Издательство:Иностранный паблик

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Student's History of England, v. 1: B.C. 55-A.D. 1509: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Student's History of England, v. 1: B.C. 55-A.D. 1509»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Student's History of England, v. 1: B.C. 55-A.D. 1509 — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Student's History of England, v. 1: B.C. 55-A.D. 1509», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

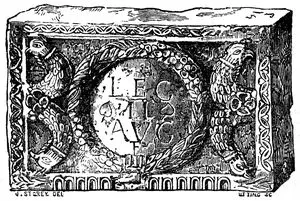

Commemorative tablet of the Second Legion found at Halton Chesters on the Roman Wall.

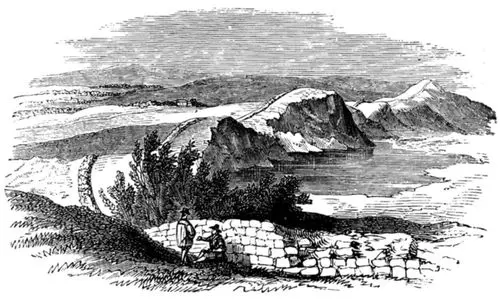

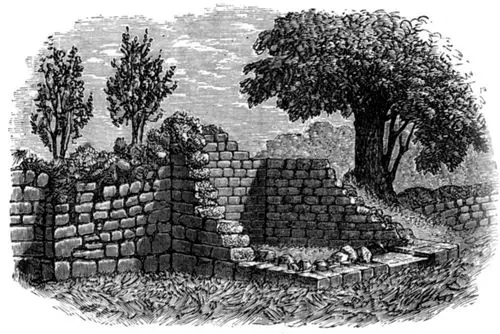

24. The Roman Walls.—Agricola, in addition to his line of forts between the Forth and the Clyde, had erected detached forts at the mouth of the valleys which issue from the Highlands, in order to hinder the Caledonians from plundering the lower country. In 119the Emperor Hadrian visited Britain. He was more disposed to defend the Empire than to extend it, and though he did not abandon Agricola's forts, he also built further south a continuous stone wall between the Solway and the Tyne. This wall, which, together with an earthwork of earlier date, formed a far stronger line of defence than the more northern forts, was intended to serve as a second barrier to keep out the wild Caledonians if they succeeded in breaking through the first. At a later time a lieutenant of the Emperor, Antoninus Pius, who afterwards became Emperor himself, connected Agricola's forts between the Forth and Clyde by a continuous earthwork. In 208the Emperor Severus arrived in Britain, and after strengthening still further the earthwork between the Forth and Clyde, he attempted to carry out the plans of Agricola by conquering the land of the Caledonians. Severus, however, failed as completely as Agricola had failed before him, and he died soon after his return to Eboracum.

View of part of the Roman Wall.

Ruins of a Turret on the Roman Wall.

Part of the Roman Wall at Leicester.

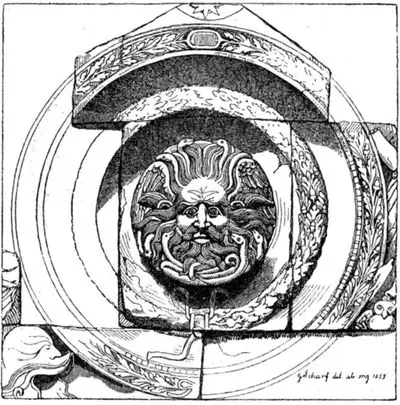

Pediment of a Roman temple found at Bath.

25. The Roman Province of Britain.—Very little is known of the history of the Roman province of Britain, except that it made considerable progress in civilisation. The Romans were great road-makers, and though their first object was to enable their soldiers to march easily from one part of the country to another, they thereby encouraged commercial intercourse. Forests were to some extent cleared away by the sides of the new roads, and fresh ground was thrown open to tillage. Mines were worked and country houses built, the remains of which are in some places still to be seen, and bear testimony to the increased well-being of a population which, excepting in the south-eastern part of the island, had at the arrival of the Romans been little removed from savagery. Cities sprang up in great numbers. Some of them were at first garrison towns, like Eboracum, Deva, and Isca Silurum. Others, like Verulamium, near the present St. Albans, occupied the sites of the old stockades once used as places of refuge by the Celts, or, like Lindum, on the top of the hill on which Lincoln Cathedral now stands, were placed in strongly defensible positions. Aquæ Sulis, the modern Bath, owes its existence to its warm medicinal springs. The chief port of commerce was Londinium, the modern London. Attempts which have been made to explain its name by the Celtic language have failed, and it is therefore possible that an inhabited post existed there even before the Celts arrived. Its importance was, however, owing to its position, and that importance was not of a kind to tell before a settled system of commercial intercourse sprang up. London was situated on the hill on which St. Paul's now stands. There first, after the Thames narrowed into a river, the merchant found close to the stream hard ground on which he could land his goods. The valley for some distance above and below it was then filled with a wide marsh or an expanse of water. An old track raised above the marsh crossed the river by a ford at Lambeth, but, as London grew in importance, a ferry was established where London Bridge now stands, and the Romans, in course of time, superseded the ferry by a bridge. It is, therefore, no wonder that the Roman roads both from the north and from the south converged upon London. Just as Eboracum was a fitting centre for military operations directed to the defence of the northern frontier, London was the fitting centre of a trade carried on with the Continent, and the place would increase in importance in proportion to the increase of that trade.

Roman altar from Rutchester.

26. Extinction of Tribal Antagonism.—The improvement of communications and the growth of trade and industry could not fail to influence the mind of the population. Wars between tribes, which before the coming of the Romans had been the main employment of the young and hardy, were now things of the past. The mutual hatred which had grown out of them had died away, and even the very names of Trinobantes and Brigantes were almost forgotten. Men who lived in the valley of the Severn came to look upon themselves as belonging to the same people as men who lived in the valleys of the Trent or the Thames. The active and enterprising young men were attracted to the cities, at first by the novelty of the luxurious habits in which they were taught to indulge, but afterwards because they were allowed to take part in the management of local business. In the time of the Emperor Caracalla, the son of Severus, every freeman born in the Empire was declared to be a Roman citizen, and long before that a large number of natives had been admitted to citizenship. In each district a council was formed of the wealthier and more prominent inhabitants, and this council had to provide for the building of temples, the holding of festivals, the erection of fortifications, and the laying out of streets. Justice was done between man and man according to the Roman law, which was the best law that the world had seen, and the higher Roman officials, who were appointed by the Emperor, took care that justice was done between city and city. No one therefore, wished to oppose the Roman government or to bring back the old times of barbarism.

27. Want of National Feeling.—Great as was the progress made, there was something still wanting. A people is never at its best unless those who compose it have some object for which they can sacrifice themselves, and for which, if necessary, they will die. The Briton had ceased to be called upon to die for his tribe, and he was not expected to die for Britain. Britain had become a more comfortable country to live in, but it was not the business of its own inhabitants to guard it. It was a mere part of the vast Roman Empire, and it was the duty of the Emperors to see that the frontier was safely kept. They were so much afraid lest any particular province should wish to set up for itself and to break away from the Empire, that they took care not to employ soldiers born in that province for its protection. They sent British recruits to guard the Danube or the Euphrates, and Gauls, Spaniards, or Africans to guard the wall between the Solway and the Tyne, and the entrenchment between the Forth and the Clyde. Britons, therefore, looked on their own defence as something to be done for them by the Emperors, not as something to be done by themselves. They lived on friendly terms with one another, but they had nothing of what we now call patriotism.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Student's History of England, v. 1: B.C. 55-A.D. 1509»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Student's History of England, v. 1: B.C. 55-A.D. 1509» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Student's History of England, v. 1: B.C. 55-A.D. 1509» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.