“Don’t touch me if you don’t mean it.”

A look of hurt, maybe even insult, fell across Lexie’s face. “I always mean it when I touch. It just may not mean what you think it does.” She reached forward again, touching him, and this time the Schwa allowed it. Cupping his face in both of her hands, she moved her thumbs across his cold, red cheeks. It was her way of looking him in the eye.

“Antsy is not your only friend. And you have never once slipped my mind.”

I could see the Schwa trying to blink away tears. I don’t know exactly what he felt at that moment, but I did know that he was done with sitting in the road, feeling sorry for himself.

“Come on, Calvin,” I said. “There’s someplace we need to go.”

“Where?”

I took a deep breath. It was time he had his own dose of trauma therapy.

“We’re paying a visit to the Night Butcher.”

***

“I’m not getting out of the car,” he told me when we pulled to a stop in the parking lot of Waldbaum’s supermarket.

“If you don’t get out, you’ll never know what happened.”

“Well, I’m getting out,” said Lexie, irritated that I had kept what little I knew from her. “Even if you don’t want to hear, Calvin, I do.”

In the end, he got out with us, and the three of us walked to the supermarket with the grave determination of my mother on double-coupon day.

We passed the checkers, who were complaining about the stock boys; we passed the stock boys, who were making jokes about the checkers; and we pushed our way into the room behind the meat counter without anyone noticing or caring that we were there.

Gunther was blasting the meat-cutting room with a steam hose to disinfect the stainless-steel instruments. It was a frightening noise to walk in on. A screeching hiss filled the air, which was stifling and humid. When he saw us, he stopped. He didn’t yell at me this time, or make accusations. He didn’t demand that we leave. He just studied us for a moment, the hose now silent in his hand.

“This is him, then? The friend?”

“This is him,” I answered.

“His name is Calvin,” Lexie added.

Gunther took a look at Lexie, opened his mouth as if to ask something stupid like, “This one is blind?,” but thought better of it. He put down his hose and pulled up a few chairs, the chair legs squeaking on the sweating tile floor. We all sat in silence, which was somehow worse than the awful hiss.

“You have to understand it was none of my business,” Gunther began. “None of my business at all. This is why I don’t speak sooner. Other people, they talk, talk, talk until words mean nothing. There is no truth.” He pointed to his chest. “I keep truth here. Not in other people’s ears. So you know what I say is true.”

The Schwa hung on his every word, clutching the edge of his chair just like Crawley did in the helicopter. Gunther didn’t speak again for a while. Maybe he wanted us to drag it out of him. Maybe he thought it was a game of twenty questions.

“Tell me what happened to my mother,” the Schwa said. It turns out all Gunther was waiting for was the proper invitation—and although he claimed that his memory wasn’t what it used to be, it didn’t stop him from remembering things with the detail of a police report.

“The woman—your mother. She would come here all the time. Those were the days that I worked the swing shift usually. Four to midnight. Busy time. Always busy time. People rushing home from work. Dinners to make. So I always come early. Help out the day butcher. Half an hour, maybe an hour early. Your mother—I remember she came. I don’t remember her face. Isn’t that strange? I can’t remember her face.”

I looked to the Schwa to see how he would react. He didn’t flinch.

“I do remember that she was not a happy woman,” Gunther continued. “No joy in her eyes, or in her voice. The way she would reach for meat. It was as if just the reaching was a burden. As if to lift her arm took all the strength of her soul. I see many people like this, but few as unhappy as her.”

“Does this sound right, Calvin?” Lexie asked.

The Schwa shrugged. “I guess.”

“Go on,” I said. “Tell us about that day.”

“Ya, the day.” Gunther glanced at the door, to make sure no one would come in to disturb us. “The other butcher who worked here during the day—Oscar was his name—he hated his job. He was a third-generation butcher. In three generations the blood can thin. No passion. No love for the work.”

“He couldn’t stand the daily grind,” said Lexie. I snickered, but quickly shut myself up.

“I never trusted him,” Gunther continued. “He was unpredictable. How do you say . . . impulsive. He would say such things! He said he would someday slam a cleaver in the manager’s desk, and walk out. Or he would threaten to cut the meat into strange, unnatural shapes, just to confuse the customers. I would have to talk him out of such things. He spoke to me of travels he never took to places he wished to go. Alaska, the Florida Keys. Visit the Hopi Indians, kayak the Colorado River. All talk. He never went. Oscar spent his vacations at home alone, and the pressure, it would just build. I didn’t know how, I didn’t know when, but I knew it was only a matter of time until he snapped. Maybe, I thought, the cleaver would wind up in the manager’s head instead of his desk. Or maybe ... maybe something worse.”

“What does this have to do with my mother?” the Schwa asked impatiently.

“Very much to do with your mother,” Gunther said. “Because your mother was there when he finally snapped.” Gunther leaned forward, looking directly at the Schwa. It was like me and Lexie were no longer in the room.

“Actually,” Gunther said, “it was your mother who snapped first. I was right here in the back room when I heard it. This woman crying. Crying like someone had died. Crying like the world had come to an end. I don’t do well with crying women. I stayed back. Oscar was the emotional butcher—he was best with the emotional customers, so I let him talk to her.

“First he talked to her over the counter, trying to calm her down. Then he took her behind the counter and sat her down. I had to take over special orders while they talked. I could hear some of what they said. She felt like she was watching her own life from the outside, as if through a spyglass. So did he. Many times she thought she might end it all. So did he. But she never did ... because more than anything, she was afraid that no one would notice that she was gone.”

I could almost see the blood draining from the Schwa’s face. He was so pale now I thought he might pass out.

“I go back to fill a special order for lamb shanks. It was the Passover, you know. Never enough lamb shanks at the Passover. When I come back, Oscar has taken off his apron, and he hands it to me. ‛I’m going,’ he says. ‛But Oscar, still you have half an hour of duty,’ I tell him. ‛Busiest time. And the Passover!’ But he doesn’t care. ‛Tell the manager the beef stops here,’ he says. Then he takes your mother’s hand, pulls her out of the chair—maybe that same chair you sit in now. He pulls her up, and now she’s laughing instead of crying, and then they run out the back way, like two cuckoos in love. That’s the last anyone has ever seen of them.”

The Schwa stared at him, slack-jawed.

“There you have it,” Gunther said, crossing his legs in satisfaction. “Do you want me to tell it again?”

The Schwa’s head began to shake, but not in the normal controlled way. It kind of moved like one of those bobble-head dolls. “My mother ran away with the butcher?”

Читать дальше

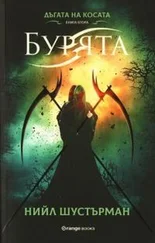

![Нил Шустерман - Жнец [litres]](/books/418707/nil-shusterman-zhnec-litres-thumb.webp)