‘You’re right about the Church,’ he says. ‘The Church’s position is perfectly clear. What you’ve done is wrong. But it’s done. And your duty now, as far as the Church is concerned, is also perfectly clear.’

‘Yes,’ says Larry. ‘I realise that.’

‘But marriage is for ever. It’s till death.’

‘Yes,’ says Larry.

His father was married till death. Nine years, and then death. Those nine years have crystallised into a sacred monument. The perfect marriage.

‘Can you do that, Larry?’

‘I don’t know,’ says Larry. ‘How do you know? Did you know?’

His father gives a slow emphatic nod. No words. He has never spoken about his dead wife. Never mentioned her name since her death, except in their prayers. God bless Mummy and watch over us from heaven and keep us safe till we meet again .

Watch over me now, Larry thinks, wanting to cry.

‘I’m not your priest,’ says his father. ‘I’m your father. I want to say something the Church can’t say to you. If you don’t really love this girl, you would be doing a wicked thing if you married her. You would be condemning both of you, and your children, to a life of unhappiness. From what you tell me, she understands this very well. She doesn’t want a husband who is merely doing his duty. Of course, whatever happens, you must support her. But if you marry, marry of your own free will. Marry for love.’

Larry is unable to speak. In every word his father utters, he feels the powerful force of his love for him. He may use the language of moral imperatives, but his underlying concern is for his son’s happiness. This is what it is to be a father. He’s willing to set aside even his most deeply cherished beliefs for the sake of his child.

‘Don’t ruin your life, Larry.’

‘No,’ says Larry. ‘That is, if I haven’t already.’

‘But if you think you really can love her – well then.’

Larry meets his father’s eyes. He wants so much to hug him, and feel his father’s arms holding tight. But it’s years since they hugged.

‘There’s the practical side of things,’ he says. ‘You say I must support her, and of course I must. But it’s not so simple.’

‘I take it,’ says his father, ‘that art has not proved to be remunerative so far.’

‘Not so far.’

Now his father will tell him that this is just as he predicted in their one great row before the war. That he’s wasted his youth on a foolish dream. That now he must face up to his responsibilities.

‘But you love it?’

‘I’m sorry?’

‘Your painting. Your art. You love it.’

‘Oh, yes.’

‘You sound very certain about that.’

‘You’re asking me if I love to paint, Dad. I am certain of that. It’s all I want to do. But I’m not certain about anything else. I’m not certain that I’m good enough. I’m not certain I’ll ever be able to make my living at it.’

‘But you love it.’

‘Yes.’

‘That’s a rare thing, Larry. That’s a gift from God.’

Abruptly he gets up from his chair and goes to the desk where he keeps his private papers. For a few moments he fiddles about, consulting the pages of his ledgers.

‘Here is what I propose,’ he says. ‘I will increase your allowance by an additional £100 a year. I will pay for the rental of an appropriate flat for this young lady. Whether you live there with her, and upon what terms, is entirely your own business. How will that do?’

‘Oh, Dad!’

‘I’m trying to be practical about this, Larry. It’s not for me to judge you.’

‘I thought you’d tell me to take a job in the company.’

‘What, as a punishment? The company isn’t a penal colony. If you ever join the company, it must be of your own free will.’

‘Like marriage.’

‘Yes. Very like.’

He holds out his hand. Larry takes it and grasps it.

‘Let me know what you decide.’

* * *

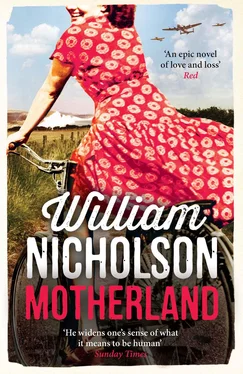

Bicycling back across London, Larry finds himself once more tossed this way and that by conflicting emotions. His father’s generosity awes him and leaves him floundering. Without realising it, he now knows he had gone home to receive instruction in his duty. Unable to take the decision himself, he looks to the institutions that frame his life, family, school, church, to force his hand. Instead he leaves his father’s house freer and more empowered than when he arrived; and therefore more solitary and more burdened.

How is it that others make this decision so easily? Do they feel absolute certainty? He thinks then of Ed and Kitty. They met twice – twice! – before deciding to marry. At the time he felt no surprise: why should love require more than an instant? And in wartime there was always too little time, and only a very uncertain future. But let peace break out, let the future stretch before you for its full span of years, and who can know for certain what they want?

So maybe, he thinks, it’s this very demand for certainty that’s the stumbling block. If certainty is impossible, then why expect it? Perhaps the decision to marry is a provisional one, made on best information at the time, and it takes years to grow into certainty. If this is the case, all that’s needed to kick-start the process is some outside pressure. And what could be a more traditional outside pressure than a baby on the way? In some countries it’s understood that no engagement takes place until the girl is pregnant; that, and not sex, being the purpose of marriage.

But what about love?

Still debating within himself, he turns into the road where he lives, and there’s Nell, sitting on the steps, looking out for him. She jumps up, her face grinning from side to side.

‘Guess what?’ she says. ‘I’ve been at Julius’s. He says your pictures are all sold!’

‘Sold! Who to?’

‘Some anonymous buyer. Isn’t that wonderful? You’re being collected! Like a real artist!’

‘I’m amazed.’

‘It’s good, isn’t it?’

He feels a sudden exultation as the news sinks in. His paintings are wanted. Money has been paid for them. There’s no endorsement quite as gratifying as this. Words cost the speaker nothing. But no one pays out real money unless they mean it.

He props his bike against the wall and takes Nell in his arms. Her excitement is all for him. In this time of crisis for herself, she thinks only of him.

‘I couldn’t wait to tell you. I’ve been sitting on the steps hugging myself.’

‘It’s brilliant,’ he says. ‘I can’t believe it.’

He kisses her, there on the steps.

‘We have to celebrate,’ she says.

‘Yes, but what about your message?’

‘Oh, that,’ she says. ‘Did you manage to get it out of the bottle without breaking it?’

‘No. I had to smash it.’

‘I thought you might.’

‘You shouldn’t have run away.’

‘Shouldn’t I?’

She’s in his arms, and she’s smiling up at him, and she’s so funny and beautiful, and his paintings have sold and the sun is shining, and suddenly it seems easy.

‘Marry me, Nell.’

She goes on smiling at him, but says nothing at all. This isn’t how it’s supposed to be.

‘Nell? I asked you a question.’

‘Oh, it was a question, was it?’

‘I want you to marry me.’

‘Maybe,’ she says. ‘I’ll think about it.’

‘Don’t you want to?’

‘Maybe,’ she says. ‘I’m not sure.’

‘You’re not sure!’

‘Well, I am only twenty.’

‘Almost twenty-one.’

‘But I do love you, Lawrence.’

‘There you are, then,’ he says.

‘I just don’t know that I’d be good for you.’

‘Of course you would!’ Hearing her express her doubts frees him of his own. ‘You’re perfect for me. You’re good to me, and you never stop surprising me, and you make me happy. How am I to live without you?’

Читать дальше