Alone now among the trees, seeing only the same patterns of light and shade in every direction, it seems to her that with her new deeper past has come a deeper future. Her life extends infinitely backwards, but also forwards. The story her grandmother has told has shown her, as if from a great height, her own place in time. This immensity is consoling. One life can contain so much.

She returns to the house, and finds Pamela taking her breakfast on the terrace. She joins her, and drinks another cup of coffee.

‘I was thinking,’ her grandmother says, ‘before you go home maybe we should visit the graves.’

‘The graves?’

‘They’re buried here, in Bellencombre. My mother, and Larry. Larry made it to eighty-four, not such a bad age. I was with him when he died.’

‘Here?’

‘Yes, here. This was his house. This is where they lived in their later years.’

Somehow this comes as a surprise. After the long story of the distant past, it brings them shockingly close. I could have met them, Alice thinks. I could have known them.

‘I adored Larry,’ says Pamela. ‘Really he was the one I wanted to marry.’

‘But you married Hugo.’

‘Yes. Poor Hugo. All frightfully Freudian, I suppose. Except I can’t help thinking Freud got it all wrong. I was never in competition with my mother. I loved her far too much for that. No, it was all the other way about. I wanted to be my mother.’

* * *

They drive in to Bellencombre and visit the graveyard by the side of the church of St Martin. Here Kitty and Larry lie buried in the same grave. The headstone, looking disconcertingly new, bears only their names and dates. Kitty is named as Katherine Avenell.

‘They were together for just over fifty years,’ says Pamela.

‘Were they happy together?’ says Alice.

‘Yes, they were very happy.’

‘They deserved to be happy.’

‘Why do you say that? Because Larry had waited for so long?’

‘I suppose so,’ says Alice.

‘He wasn’t just a sweet patient man waiting in the wings, you know. His love was the biggest thing in all our lives. It was like a blazing fire in the room. Love can be so ruthless, can’t it?’

They walk back between the headstones to the waiting car. Alice is silent, thinking.

‘Has any of that helped you?’

’In a way,’ says Alice.

* * *

Why should love end? Once you start loving someone the love continues to grow and change for the rest of your life. But we’re all so afraid, so unsure we’re lovable, so fragile. We want love never to change.

I’m growing stronger now. I want a life of my own. I want adventures of my own. If one day I marry and have children, I want to be able to make that commitment as a woman who knows she deserves to be loved.

I come from a long line of mistakes. And one true love story.

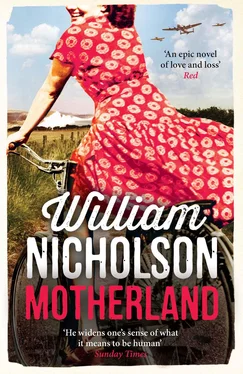

The historical background to the events in Motherland is as accurate as I have been able to make it. The account of the Dieppe raid is based on several first-hand reports, in particular by the war journalists A.B. Austin, Quentin Reynolds, and Wallace Reyburn.

My knowledge of the events surrounding Indian independence began when I was asked to write a screenplay based on Alex von Tunzelmann’s excellent Indian Summer . For the details I have relied heavily on Alan Campbell-Johnson’s diary of that time, published in 1951 as Mission with Mountbatten .

For background on William Coldstream and Camberwell College of Art in the post-war period I have been greatly helped by the first-hand memories of my mother-in-law, Anne Olivier Bell.

For the tale of Fyffes and the banana business I am indebted to my old friend David Stockley, whose father, grandfather and great-grandfather managed Elders & Fyffes for so many successful years. The business details are accurate; the character details of the fictional Cornford family are of course invented. I have relied also on A.H. Stockley’s privately printed autobiography Consciousness of Effort: The Romance of the Banana , 1937; The Banana Empire by Charles Kepner and Jay Soothill, 1935; and Fyffes and the Banana by Peter N. Davies, 1990.

In matters of historical fact and tone of voice I have relied throughout on my wife, the social historian Virginia Nicholson, whose own books, particularly Millions Like Us , her account of the lives of women in the Second World War and after, have been an inspiration to me.

Readers may be interested to trace the links between the characters in Motherland and characters in my other Sussex-based novels. Alice Dickinson appears at the age of eleven in The Secret Intensity of Everyday Life , and again aged nineteen in All the Hopeful Lovers . Her father Guy Caulder also plays a part in both novels. George Holland’s curious love life is discovered long after his death in Secret Intensity , where a very old Gwen Willis makes an appearance. Louisa, George Holland’s wife, dies in 1955, after Motherland has ended and many years before Secret Intensity begins, but her son Billy has a large part to play in the later book. Anthony Armitage, the artist, appears as an angry old man in All the Hopeful Lovers . Rex Dickinson, briefly encountered in Motherland , is the absent husband of Mrs Dickinson, who appears in Secret Intensity and The Golden Hour . The farmhouse where Larry and Rex are billeted, and where Kitty and Ed later live, appears in all three earlier novels as the home of the Broad family. Edenfield Place appears in all four novels, at different stages of its existence. This great Victorian Gothic house is based on Tyntesfield, the Gibbs family mansion near Bristol, now owned by the National Trust.

William Nicholson’s plays include Shadowlands and Life Story , both of which won the BAFTA Best Television Drama award of their year. He co-wrote the script for the film Gladiator , and, more recently, he has scripted Les Miserables and Mandela . He is married to the writer Virginia Nicholson and they have three children. William Nicholson lives in East Sussex.

Also by William Nicholson

The Trial of True Love

The Society of Others

The Secret Intensity of Everyday Life

All the Hopeful Lovers

The Golden Hour

Books for children

The Wind Singer

Slaves of the Mastery

Firesong

Seeker

Jango

Noman