According to Cain, Double Indemnity was inspired by a story he once heard about a newspaper typesetter who, after many years of faithful service, could not resist allowing a salacious error to slip into a headline. A similar idea was carried over into the film: as Chandler might have put it, both versions of the story deal with an organization's attempt to "destroy the link" between a worker and his unconscious. In depicting the operations of big business, however, the film creates a much more powerful sense of alienation than Cain had done, and it has a greater propensity toward gallows humor. The last of these qualities can undoubtedly be attributed to Wilder, who was the true cosmopolitan among the various authors of the project. Wilder had been a journalist in Vienna, a "gigolo" in Weimar Berlin, a scriptwriter for two celebrated German films (People on Sunday and Emil and the Detectives), and an émigré writer and director in Paris during the early 1930s. Fleeing Hitler, he made his way to Paramount via Mexicomuch like the protagonist of his 1941 screenplay, Hold Back the Dawn, which, in its original form, was a comedy involving a man in a hotel room who tells his life story to a cockroach. He knew the seamy and the sophisticated sides of both Europe and Los Angeles, and he had been scarred by modern history. The grimmest irony of Double Indemnity, which he did not know at the time, was that his own mother had been gassed at Auschwitz only a year or two before the film began production.

Because of Wilder, Double Indemnity is profoundly indebted to Weimar Germanynot so much in its photographic style (which reviewers of the time compared with the prewar French cinema), but in its imagery of Fordist Amerika. On the level of language alone, as William Luhr points out, the film is pervaded with grimly deterministic metaphors of modern industry: the lovers promise to remain committed to one another "straight down the line"; Walter devises a clockwork murder involving a train, and when he puts his plan in motion he remarks that "the machinery had started to move and nothing could stop it"; later, looking back over his crime, he claims that fate had ''thrown the switch" and that the "gears had meshed." These metaphors are reinforced by equally oppressive visuals; for instance, when we first enter the Pacific All-Risk Insurance Company, the camera tracks over Walter Neff’s shoulder and looks down into a dark, cavernous room lined with rows of empty desks, each equipped with identical blotters and reading lamps. The design here is strongly reminiscent of German silent films such as Murnau's Last Laugh and of German-inspired Hollywood movies such as King Vidor's Crowd, Paul Fejos's Lonesome, and the Ernst Lubitsch episode of If I Had a Million. (It can also be seen in Welles's Trial, and in Wilder's later picture, The Apartment .) In all its manifestations, it signifies the tendency of modern society to turn workers into zombies or robots, like the enslaved populace of Lang's Metropolis. 62

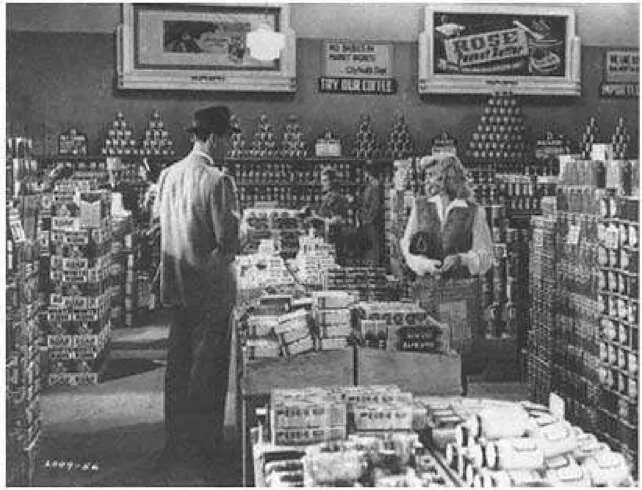

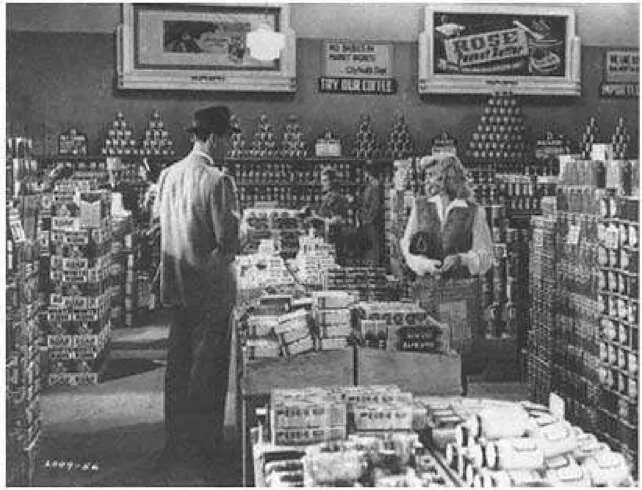

The theme of industrialized dehumanization is echoed in the relatively private offices on the second floor of the insurance company, which are almost interchangeable, decorated with nothing more than statistical charts and graphs. Meanwhile, Walter's apartment looks like a hotel room, and the funereal Dietrichson home is described as "one of those California Spanish houses that everyone was nuts about ten or fifteen years ago." 63The public world is equally massified: when Walter realizes that Phyllis wants to murder her husband, he drinks a beer in his car at a drive-in restaurant; then he goes to a bowling alley at Third and Weston, where he bowls alone in an enormous room lined with identical lanes. The most surreal instance of mechanical reproduction, however, is Jerry's, "that big market up at Los Feliz," where Walter and Phyllis plan their crime. Walter and Phyllis hold sotto voce conversations across aisles filled with baby food, beans, macaroni, tomatoes, and seemingly anything else that can be packaged and arranged in neat rows; they talk about murder in public, but the big store makes them anonymous, virtually invisible to shoppers.

Phyllis (Barbara Stanwyck) is associated with nearly all the locales I have been describing, whereas Lola Dietrichson (Jean Heather) is photographed against the forests of the Hollywood hills and the beaches at Santa Monica. Wilder's melodramatic allegory could not be more obvious: the bad girl represents Culture and the good girl represents Nature. Here again Wilder's indebtedness to Weimar is evident. As I have already indicated, German cinema of the 1920s often used the decadent eroticism of the late nineteenth century to express growing fears of the "new woman." The flapper in Pandora's Box and the city woman in Sunrise were intended to suggest an urbanized, mass-cultural type that the Germans both loved and hated. Phyllis belongs in the same category; indeed, she is so bad that she seems like modernity and kitsch incarnatea realist version of the "false Maria" in Metropolis.

This implication becomes especially clear when we place the movie Phyllis alongside the femme fatale in Cain's novella, who is an ordinary, rather earthy woman with a "washed out face" and a "shape to set a man nuts" (10). The character portrayed by Barbara Stanwyck is much more blatantly provocative and visibly artificial; her ankle bracelet, her lacquered lipstick, her sunglasses, and above all her chromium hair give her a cheaply manufactured, metallic look. In keeping with this synthetic quality, her sex scenes are almost robotic, and she reacts to murder with an icy calm. "She was perfect," Walter remarks at one point. "No nerves, not a tear, not even a blink of the eye." 65

Unlike Cain, Wilder and Chandler create a soulless, modernized female whom they can easily kill off (even though she seems to need a lover's embrace in the moment before she dies). They also make Walter's amour fou look affectless. Their whole point seems to be that under modernity, lovemaking is reified and "mechanical." As a result, despite all its suggestive dialogue, Double Indemnity generates most of its warmth when it dramatizes the platonic relationship between Walter Neff and Barton Keyes. Throughout, these two organization men form a sort of Odd Couple: one is tall and handsome, the other short and plain; one smokes cigarettes, the other cigars; one is a "peddler, gladhander, backslapper," the other a quintessential analyst and statistician; one is a criminal, the other a detective. They are nevertheless alike in their regard for one another's skill and in their mutual contempt for their boss. Keyes enjoys lecturing Walter about the insurance business and at one point offers to recommend him for a promotion to the claims department. For his part, Walter recognizes that behind Keyes's gruff exterior is a sharp intelligence and "a heart as big as a house." One of the ironies of Walter's crime is that in betraying his employer, he is also betraying a friend and a father substitute; hence his interoffice message, which is not only a confession of guilt but also an admission of love.

"Jerry's, that big market up at Los Feliz."

(Museum of Modern Art Stills Archive.)

The last scene of the released print of Double Indemnity makes this Chandleresque theme of male friendship and betrayal clear. In classic fashion, it repeats and reverses two motifs from earlier in the picture: Keyes provides Walter with a match, and Walter says "I love you, too," in a more serious tone than he has used before. Notice also that Keyes is given a kind of moral authority. As he predicted in a speech containing one of the film's most vivid metaphors of mechanical destiny, the killers of H. S. Dietrichson have stepped onto a trolley line, and it's a one-way trip: at the end of the line is death. Keyes becomes a saddened, paternal on-lookera wise man who, according to Richard Schickel's BFI monograph on the film, should never have been "spurned" by a fatally "mixed up guy" like Walter. 66

Читать дальше