No such problems affected Greene's later and much more famous movie, The Third Man (1949), an international coproduction based on an original screenplay by Greene, which was financed in Hollywood style by Alexander Korda and David Selznick. In contrast with Brighton Rock, this film treats Greene's religious themes with a discreet irony: at one point Harry Lime tells his friend Holly Martins, "Of course I still believe, old man. . . . I'm not hurting anybody's soul by what I do." At the same time, it features a thrilling chase sequence by Carol Reed, a popular music score by Anton Karas, and a memorable star performance by

Orson Welles. It therefore fulfills Greene's long-standing desire to make an effective thriller that also functions as an art movie. On the second of these levels, The Third Man offers not only the neo-Calagarisme of Carol Reed's tilted camera, but also a quasidocumentary tour of Vienna, one of the cradles of both modernism and Hitlerian fascism, which has been reduced by the war to a kind of "Greeneland." Consider, too, the thematic and technical elements of Greene's screenplay. The protagonist and narrator of the story, Holly Martins, resembles both a Jamesian innocent and a Conradian secret sharer. Like Marlow in Heart of Darkness, Martins is an impetuous, sentimental romantic; also like Marlow, he searches out a villain who makes a delayed entrance, after being described by several people. Significantly, one of these narrators is a man named Kurtz, who, in a conversation with Martins, claims to have been Harry Lime's best friend"after you, of course."

As everyone now knows, Orson Welles wanted to make his own film of Heart of Darkness, which he put aside shortly before making Citizen Kane. Here, merely by virtue of his charm, he transforms Harry Lime into the most dangerous of the "angelic" or Luciferian killers who populate Greene's fiction. His entrance is so impressive that it tends to make the audience forget exactly what crimes Lime is supposed to have committed (something involving black-market penicillin and dead babies). What everyone recalls is a burst of zither music and a series of images that confirm Greene's 1928 argument about the "poetic" force of silent movies: a tall figure slipping into the shadowed doorway of a house (the home of the young Mozart); a cat licking a pair of black Oxfords; and a sudden, spotlighted view of Welles in a black hat and topcoat, the camera zooming toward him as he smiles like a ham actor who has been caught doing something naughty.

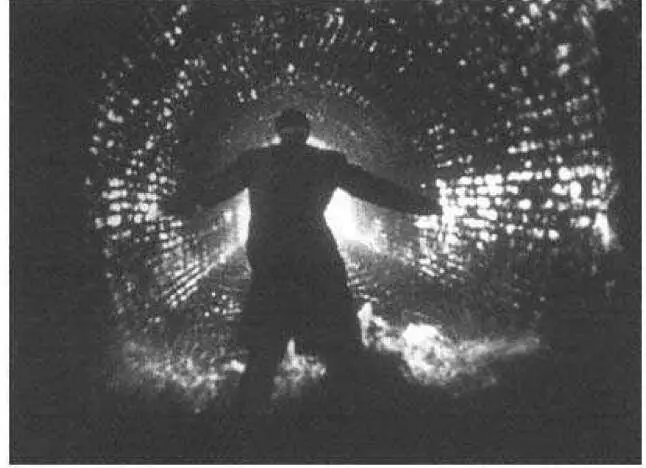

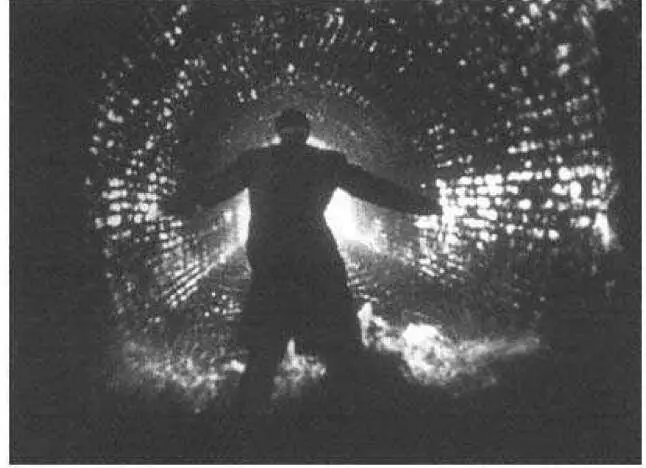

"Don't be melodramatic, old man," Harry Lime says to Holly Martins as they ride the giant Ferris wheel above Vienna. But of course Lime (whose name has an affinity with Greene) is the most melodramatic character in the filma dashing, flamboyant outlaw, reminiscent of Fantomas or the Shadow. The naive Martins adores him, and because Martins is played by Joseph Cotten, we cannot help but be reminded of Jed Leland's relationship with Charles Foster Kane. The beautiful and masochistically romantic Anna (Alida Valli) pines for him, even after he turns her over to the Soviet authorities. For these two and for the audience, Lime provides a glamorous alternative to the social engineering in postwar Vienna, where the forces of modernity have divided a "smashed and broken" city into four zones, and where the charming old ring at the center is patrolled by military units representing each of the occupying powers. The cold war has already begun, and daily life for the Viennese is constricted by rationing, checkpoints, identification papers, and worthless currency. Lime operates above and below this worldchiefly in the miraculously clean and undivided sewers, where the police wear white uniforms resembling those of a ski patrol. The most beautiful, dramatically lit scenes in the picture take place in his watery underground, and one of the most poignant sequences is the moment when he is trapped and killed there by a man who has always loved him. 49

Three "angelic killers" in films based on Graham Greene: Alan Ladd in This Gun for Hire (1942), Richard Attenborough in Brighton Rock (1946), and Orson Welles in The Third Man (1949).

In this film, however, the seductions of melodrama are never offered without countervailing irony or deflation. Martins is an American "scribbler" who specializes in pulp westerns; he has experienced outlaws only in his imagination, and, like the movie audience, he gradually realizes that his attraction to Lime amounts to a complicity with evil. Lime, meanwhile, is revealed as a witty sociopath. During his ride on the Ferris wheel, he chews an antacid tablet and projects a fake cheerfulness, comparing himself to a modern-day bureaucrat: he, too, has a "five-year plan," the only difference being that he deals with ''the suckers" instead of "the people" and with "dots" instead of statistics.

Eventually, Lime dies. But there is something almost sacrificial about the image of his fingers reaching through a manhole cover in the street, and about Martins's coup de grâce, which is administered offscreen. After Lime is gone, the film does nothing to assuage the sense of moral ambiguity he has created. Martins and Anna do not go off into the sunset, as they do in Greene's novelized version of the story; instead, Carol Reed shows Anna walking past Martins and ignoring him as he stands near the Vienna graveyard where Lime is buried. 50Unlike most characters in a closing shot, Anna walks toward the camera and exits behind it, leaving Martins alone at the left of the screen among a line of barren trees. A moment of dead time follows, with the zither music playing and the unbalanced composition waiting to be filled. It is a remarkably artful and wistful ending, simultaneously repudiating the pleasures of melodrama and mourning their loss. In its last seconds, the film seems to wish for Lime's return, if only because he is the most colorful and "alive" person we have met.

Harry Lime, "crucified" in a sewer.

Such a delicate balancing act could only have been made possible by the forces of cultural history. The Third Man is one of the best and most representative films of a period when a certain kind of high art had fully entered public consciousness and when European sobriety and American entertainment sometimes worked in tandem. Greene was conscious of the formal dialectic required by the times, and in one of the earlier episodes of The Third Man , he comments upon it. Holly Martins is picked up by a mysterious cabdriver in front of the Sacher hotel and driven through the dark streets at high speed. "Have you got orders to kill me?" Martins shouts, but the driver ignores him, turning a corner and slamming on the brakes in front of an imposing building. The doors burst open, and the bewildered Martins finds himself at a Kafkaesque gathering of the "British Cultural Reeducation Service," where he is the guest of honor. He is introduced as ''Mr. Holly Martins, from the other side," and a series of grotesque characters pepper him with questions: "Do you believe, Mr. Martins, in the stream of consciousness?" "Now Mr. James Joyce, where would you put him?" Hopelessly confused, Martins tells the disappointed group that his chief influence is Zane Grey.

In this scene, Greene is obviously satirizing middlebrow culture (how often he must have been asked the same questions), but he is also paying homage to the literature that shaped his career. The first book he read as a child was a potboiler called Dixon Brett, Detective, and his first act upon visiting Paris in the 1920s was to make his way to Sylvia Beach's bookshop, where he purchased a copy of Ulysses. 51 The Third Man brings these two literary extremes and two kinds of pleasure into melancholy union, and in the process it achieves a distensive or double-edged irony characteristic of Greene's thrillers in general: on the one hand, the emotional flourishes and intensities of melodrama are treated with modernist skepticism; but on the other hand, scenes of everyday life are haunted by a bloody and romantic passion.

Читать дальше