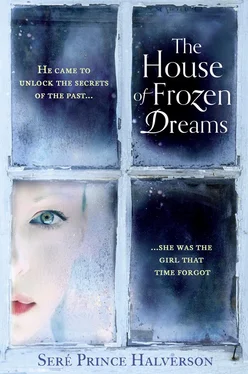

Kache swallowed hard. Snag held his elbow, moved a lock of white hair from Gram’s vein-mapped forehead. “Mom, Kache has been away. Just away. From here.”

Gram raised her eyebrows, nodding, and rubbed Kache’s long hand between her two boney speckled ones. “Of course you have, dear. Oh, but …” She looked over her shoulder, then back at him. Her voice raised higher, almost a child’s. “It was like all four of you were dead. Now. At least we have you back.” She picked up his hand in hers, moving it up and down to the beat of each word: “And. That . Is a. Very. Good. Thing.”

“Thanks, Gram.” How had he stayed away so long? How had he come back? He was tempted to grab himself a wheelchair and steal the remote from the guy in the Hawaiian shirt and cardigan, flip the channel to the DIY network, and let a few more decades go flickering past.

Instead, he drove with Snag over to her place. He braced himself for the onslaught of mementos but, surprisingly, Snag didn’t have one piece of furniture or even a knick-knack or painting of his mother’s. Sentimental Aunt Snag, who loved her brother and adored her sister-in-law. Where was all their stuff? It didn’t make sense to sell or give away every single thing. And when Kache asked about heading out to the homestead she changed the subject. She wouldn’t have sold it, would she? He knew she’d sold his dad’s fishing boat right away to Don Haley, but all four hundred acres, without saying a word to Kache? It was true that Kache had given her power of attorney, back when he was eighteen and didn’t want to deal. But she wouldn’t have sold it without telling him. No way.

Later that afternoon he went to the Safeway for her and bumped into an old friend of his father’s, Duncan Clemsky. Duncan clapped him on the back, kept shaking his hand while he talked. “Look at you, Mr. City Slicker. I still think of you when I have to drive by the road to your daddy’s land. Only time I get out that far is when I make a delivery to the Russian village.”

“The Old Believers are accepting deliveries these days? Progressive of them.”

“Some of them at Ural even have satellite dishes. Going soft. Won’t be long until they’re wearing pretty, useless boots like those.” He nodded toward Kache’s feet. “Change eventually gets ahold of everyone I suppose.”

“Suppose so,” Kache said, his face heating up. Nothing like a lifelong Alaskan to put you in your place. He wanted to ask Duncan if Snag had sold the land, but he wasn’t about to let on he didn’t know—if it was even true. No need to get a rumor heading through town that would end up like one of the salmon on the conveyor belt down at the cannery, the head and tail of the story cut off and the middle butchered up until it became something unrecognizable.

“You’re gonna need to get some real boots before folks start mistaking you for a tourist from California. Thought you were at least in Texas, my man.” He shook his head and winked. “You tell your aunt and grandma I said hello, will you?”

Kache nodded. “Will do, Duncan. Same goes for Nancy and the kids.”

That opened up another ten minutes of conversation, with Duncan Clemsky filling Kache in on every one of his five kids and sixteen grandchildren, and seven seconds of Kache filling Duncan in on the little that Kache had been up to for the last twenty years. “Yeah, you know … working a lot.”

On the way back to Snag’s, Kache decided that if she didn’t bring up the homestead that evening, he would just come out and ask her if she’d sold it. Part of him hoped she had, the other part hoped to God she hadn’t.

Snag filled the sink with the hottest water she could stand while Kache cleared the dinner dishes. She’d decided on Shaklee dishwashing liquid, since she’d used Amway for lunch and breakfast, and now she was trying to decide how on earth to tell Kache about the homestead.

Staring at her reflection in the kitchen window, she saw a chickenshit, and a jealous sister, and there was no hiding it. Looking at it, organizing the story in her mind, lining it up behind her lips: This is how I let it happen. It started this way, with my good intentions but my weaknesses too, and then a day became a week became a year became a decade became another. I hadn’t meant for it to happen like this, I hadn’t meant to.

She squeezed more of the detergent; let the hot water cascade over her puffy hands. She laid her hands flat along the sink’s chipped enamel bottom, where she couldn’t see them beneath the suds. If only she were small enough to climb into the sink and hide her whole self, just lie quietly with the forks and knives and spoons until this moment passed and she no longer had to see herself for what she really was. Sometimes drowning didn’t seem so horrible when she thought of it in those terms. Better than dying the way Glenn and Bets and Denny had. She shivered even though her hands and arms were immersed in the liquid heat.

It would have brought them honor in some small way, if she’d done the simple thing everyone expected of her. Simply take care of the house and Kache. But she’d failed at both.

“Aunt Snag?” Next to her, he held the old Dutch oven with the moose pot roast drippings stuck on the bottom. There were never any leftovers with Kache, even now that he was a grown man. “Are you okay? Want me to finish up, you catch the end of the news?”

“No … Well … Okay.” She dried her hands on the towel and started to walk out, but turned back. “I’ve got to tell you something, hon, and it’s not going to be pretty. You’re going to be real upset with me, and I won’t blame you one bit.”

“You sold the homestead.” It was a statement, not a question.

“What?” she said, though she’d heard him perfectly.

“You sold it. You sold the homestead.”

“No, hon. I didn’t. I didn’t sell it.”

He smiled, sort of, a sad, tight turning up of his mouth, while his shoulders relaxed. “I guess I’ll need to go out. Check up on things. I’ve been meaning to ask. But it’s hard, thinking about driving up, seeing it for the first time, you know? Do you go out there a lot?” Still such youthfulness to his face. He didn’t seem like a grown man who’d seen a lot of life. Snag couldn’t tell what it was, exactly. Trust? Vulnerability?

She said, “Not a lot, no.”

“Just enough to take care of things.” His voice didn’t rise in a question.

“No, not that much even.’ She breathed in deep, searched in her pockets and up her sleeve for a tissue. “I haven’t been out there at all.”

“This spring?”

“No. I mean not once. Not at all.”

“All year ?”

“No, Kache. Not all year. Not ever. Not once. I never went out like I told you I did. I planned to a million times, but I never closed it up, never got all your stuff, never put things in storage. I never …”

He stood with his mouth agape for what seemed to Snag like a good five minutes. “Wait a second. You said you’d been renting it out. No one has been out there since I left? Not even the Fosters? Or the Clemskys? Jack? Any of those people? They would have been glad to help. They would have insisted on it.”

Snag leaned against the counter for support, inhaled and exhaled. “Don’t you see? I insisted it was taken care of. I told them I’d hired someone … to scrape the snow off … patch the roof … run water in the pipes.”

“I don’t understand. Why?”

“Embarrassed by then. I hadn’t even been out since you left, to water the houseplants, or—I’d never planned to be so negligent—clean out the pantry.” She fell silent. The water dripped on and on into the sink. “I left it all. I tried, I drove part way dozens of times but then I’d chicken out and turn the car around.”

Читать дальше

![Theresa Cheung - The Dream Dictionary from A to Z [Revised edition] - The Ultimate A–Z to Interpret the Secrets of Your Dreams](/books/692092/theresa-cheung-the-dream-dictionary-from-a-to-z-r-thumb.webp)