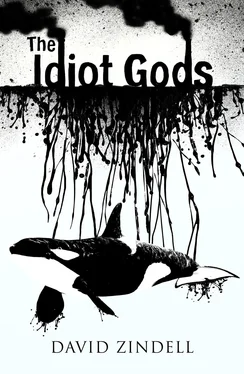

DAVID ZINDELL

The Idiot Gods

Published by HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Harper Voyager 2017

Copyright © David Zindell 2017

Cover design © HarperCollins Publishers Ltd 2017

David Zindell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007252275

Ebook Edition © July 2017 ISBN: 9780008223311

Version: 2017-05-22

To Jane, for your courage, wisdom, friendship and splendor

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Part One: The Burning Sea

Translators’ Note

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Part Two: The Idiot Gods

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Part Three: A Covenant With Thee

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by David Zindell

About the Publisher

PART ONE

It was our privilege and happy destiny to enjoy the friendship of one of the most remarkable beings ever to have come out of our little blue and white planet. Many have tried to make the orca named Arjuna into a Buddha or a Jesus, but he certainly never thought of himself as such – and not even as a teacher. Despite all insistence to the contrary, he remains an orca, however extraordinary, with all an orca’s sometimes strange and disturbing sensibilities. It is true that those who spent time with him often forgot that they were conversing with a cetacean possessing a magnitude of intelligence that we are still trying to comprehend. The consciousness of all creatures differs so greatly, yet at its source remains one and the same, as of a white light shined through a prism and refracted it into radiances of red, yellow, violet, and blue. Arjuna’s consciousness, to the extent that it illuminates his communications, can often seem pellucidly and sanely human, and at other times, psychopathic or utterly alien. We who have translated his ‘words’ faced the problem of necessarily regarding a non-human being through very human eyes; we have tried to convey a sense of Arjuna’s magnificent soul without making him seem too human. It would be well for anyone to see Arjuna for what he really is: a whale who just wanted to talk to human beings.

That Arjuna, born in the cold ocean, could have learned to ‘speak’ various human languages many still doubt, even after the seemingly miraculous events the whole world witnessed. They say that we linguists and biologists of the Institute for Advanced Cetacean Studies either misconstrued basic hunting, mating, or warning cries as language or interpreted them through our natural wish to communicate with an obviously intelligent but nevertheless inarticulate animal. Human beings, these skeptics believe, are by definition the only of earth’s creatures capable of symbolic and therefore true language. Our harshest critics – and we should hesitate before calling then conspiracy formulators – have accused us of simply inventing our translations of the thousands of communications that the orcas of the Institute confided in us. They accuse us of conspiring to excite compassion for these great beings toward the vain hope of ‘saving the whales’. This account is not for those deniers. Even if one were to read Arjuna’s account as a fiction, however, one should keep in mind that fictions often reveal the deepest of truths. In many ways, this is the truest story we know, and Arjuna had the truest of hearts. Anyone eager to know more about his life will lose little in skipping this introduction and going right to the words Arjuna chose to convey it. It is indeed a remarkable story. In the end, it is his story, and ours: that of the whole human race.

We would like to say more about those words that Arjuna selected to denote meanings that human beings could comprehend. In no way should these be considered to be ‘whale words’; whales do not communicate to each other through what we know as words, but rather through sound pictures. Arjuna offers as good an explanation of cetacean language as we could hope, and we cannot improve it. Sadly, we know almost nothing of what we sometimes informally call Orcalish. To date, even with the aid of the fastest of computers and the most elegant of mathematical models, we have managed to identify and interpret perhaps a twelfth of a percent of the meanings of the thousands of orca utterances. It should be remembered that we human beings still have not learned to speak with the whales, though they have readily, if painfully, learned to speak with us.

How, then, did Arjuna and the other orcas of his adopted family accomplish such a feat? The Institute’s former chief linguist, Helen Agar, initially worked with him in developing a constructed language through which orcas and humans could communicate. Various utterances natural to orcas – whistles, trills, clicks, chirrups, pulsed calls, and pops – were agreed upon to represent the ninety-one syllables of the language that Arjuna named Wordsong. Helen Agar had no need to speak Wordsong to Arjuna, for he understood English (and many other human languages) very well; however, while engaged in natural communication with Arjuna and the other orcas, Helen chose to communicate in this imaginative language out of solidarity with the whales and the ideal of making the crude vowels and consonants of a human language somehow ‘sing.’ Only one of the Institute’s other linguists (Prasad Choudhary) reached fluency in this language that has been popularly mischaracterized as ‘Baby Orcalish.’ In reality, Wordsong is more like a spoken Morse Code. It assigns meanings to orca sounds usually employed by the orcas very differently. Anyone can ‘talk’ Morse Code, for instance saying, ‘Pop, pop, pop; sprong, sprong, sprong; pop, pop, pop,’ to denote the SOS message meaning ‘help.’ While conversing in Wordsong is much more difficult, the rules for doing so follow a similar principle. Alone of non-linguists, the orca trainer Gabrielle Jones did come to understand Wordsong when Arjuna spoke it to her, even if she was unable to speak it back to him. English remained her only language, and it was she who encouraged Arjuna to communicate to the human race in what has become a de facto, if very limited, world language.

Читать дальше