DAVID ZINDELL

The Broken God

BOOK ONE

of A Requiem far Homo Sapiens

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events of localities is entirely coincidental.

HarperVoyager

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Publishers 1993

Copyright © David Zindell 1993

David Zindell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollins Publishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780586211892

Ebook Edition © AUGUST 2016 ISBN: 9780008122393

Version: 2016-09-01

David Zindell’s short story ‘Shanidar’ was a prizewinning entry in the L. Ron Hubbard Writers of the Future Contest. He was nominated for the ‘best new writer’ Hugo Award in 1986. Gene Wolfe declared Zindell was ‘one of the finest talents to appear since Kim Stanley Robinson and William Gibson – perhaps the finest’. His first novel, Neverness , was widely praised:

‘A thick, lush, vivid, panoramic view of evolved humans in an evolving universe far in the future’

Twilight Zone

‘Excellent hard science fiction … a brilliant novel’ Orson Scott Card

The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction

‘A victorious book, lingering and lithe and rich’

John Clute Interzone

In October 1992, a reviewer in the New Scientist referred to ‘the brilliant Neverness, in which David Zindell writes of interstellar mathematics in poetic prose that is a joy to read’

The Broken God is Zindell’s second novel and a sequel to Neverness. He lives in Boulder, Colorado.

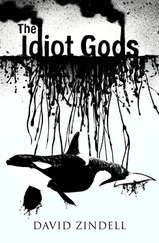

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Praise

Part One

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Part Two

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Part Three

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Keep Reading

Also by the Author

About the Author

About the Publisher

PART ONE

All that is not halla is shaida.

For a man to kill what he cannot eat, that is shaida;

For a man to kill an imakla animal, that is shaida, too.

It is shaida for a man to die too soon;

It is shaida for a man to die too late.

Shaida is the way of the man who kills other men;

Shaida is the cry of the world when it has lost its soul.

– from the Devaki Song of Life

This is the story of my son, Danlo wi Soli Ringess. I came to know him very well, though it was his fate (and my own) that he grew up wild, a lost manchild living apart from his true people. Until he came to Neverness, he knew almost nothing of his heritage or the civilized ways of the City of Light; in truth, he did not really know he was a human being. He thought of himself as an Alaloi, as one of that carked race of men and women who live on the icy islands west of Neverness. His adoptive brothers and sisters bore the signature of chromosomes altered long ago; they each had strong, primal faces of jutting browridges and deep-set eyes; their bodies were hairy and powerful, covered with the skins of once-living animals; they were more robust and vital, and in many ways much wiser, than modern human beings. For a time, their world and Danlo’s were the same. It was a world of early morning hunts through frozen forests, a world of pristine ice and wind and sea birds flocking in white waves across the sky. A world of variety and abundance. Above all, it was a world of halla , which is the Alaloi name for the harmony and beauty of life. It was Danlo’s tragedy to have to learn of halla ’s fragile nature at an early age. Had he not done so, however, he might never have made the journey home to the city of his origins, and to his father. Had he not made the journey all men and women must make, his small, cold world and the universe which contains it might have known a very different fate.

Danlo came to manhood among Alaloi’s Devaki tribe, who lived on the mountainous island of Kweitkel. It had been the Devaki’s home for untold generations, and no one remembered that their ancestors had fled the civilized ruins of Old Earth thousands of years before. No one remembered the long journey across the cold, shimmering lens of the galaxy or that the lights in the sky were stars. No one knew that civilized human beings called their planet ‘Icefall’. None of the Devaki or the other tribes remembered these things because their ancestors had wanted to forget the shaida of a universe gone mad with sickness and war. They wanted only to live as natural human beings in harmony with life. And so they had carked their flesh and imprinted their minds with the lore and ways of Old Earth’s most ancient peoples, and after they were done, they had destroyed their great, silvery deepship. And now, many thousands of years later, the Devaki women gathered baldo nuts to roast in wood fires, and the men hunted mammoths or shagshay or even Totunye, the great white bear. Sometimes, when the sea ice froze hard and thick, Totunye came to land and hunted them. Like all living things, the Devaki knew cold and pain, birth and joy and death. Death – was it not a Devaki saying, as old as the cave in which they lived, that death is the left hand of life? They knew well and intimately almost everything about death: the cry of Nunki, the seal, when the spear pierces his heart; the wailing of an old woman’s death song; the dread silence of the child who dies in the night. They knew the natural death that makes room for more life, but about the evil that comes from nowhere and kills even the strongest of the men, about the true nature of shaida , they knew nothing.

When Danlo was nearly fourteen years old, a terrible illness called the ‘slow evil’ fell upon the Devaki.

Читать дальше