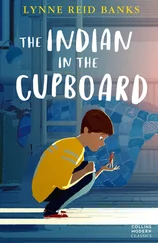

The old Indian lifted a trembling hand, and then suddenly he slumped on to his side.

“Little Bull! Little Bull! Quick, get on to my hand!”

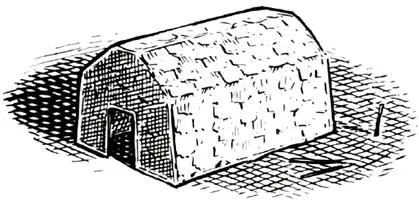

Omri reached down and Little Bull climbed on to his hand from the longhouse roof.

“What?”

“The old Indian – I think he’s fainted!”

He carried Little Bull to the cupboard and Little Bull stepped off on to the shelf. He stooped beside the crumpled figure. Taking the single feather out of the back of his own headband he held it in front of the old man’s mouth. Then he shook his head.

“Dead,” he said. “No breath. Heart stop. Old man. Gone to ancestors, very happy.” Without more ado, he began to strip the body, taking the headdress, the arrows, and the big, richly-decorated cloak for good measure.

Omri was shocked.

“Little Bull, stop. Surely you shouldn’t—”

“Chief dead; I only other Indian here. No one else to be Chief. Little Bull Chief now,” he said, whirling the cloak about his own bare shoulders and clapping the splendid circle of feathers on to his head with a flourish. He picked up the quiver.

“Omri give bow!” he commanded. And it was a command. Omri obeyed it without thinking. “Now! You make magic. Deer for Little Bull hunt. Fire for cook. Good meat!” He folded his arms, scowling up at Omri.

Omri was quite taken aback by all this. While giving Little Bull every respect as a person, he was not about to be turned into his slave. He began to wonder if giving him those weapons, let alone letting him make himself into a Chief, was such a good idea.

“Now look here, Little Bull—” he began, in a teacherish tone.

“OMRI!”

It was his father’s voice, fairly roaring at him from the foot of the stairs. Omri jumped, bumping the cupboard. Little Bull fell over backwards, considerably spoiling his dignity.

“Yes?”

“COME DOWN HERE THIS INSTANT!”

Omri had no time for courtesies. He snatched Little Bull up, set him down near his half-finished longhouse, shut and locked the cupboard and ran downstairs.

His father was waiting for him.

“Omri, have you been in the greenhouse lately?”

“Er—”

“And did you, while you were there, remove a seed-tray planted out with marrow seeds, may I ask ?”

“Well, I—”

“Yes or no.”

“Well, yes, but—”

“And is it possible that in addition you have been hacking at the trunk of the birch and torn off strips of bark?”

“But Dad, it was only—”

“Don’t you know trees can die if you strip too much of their bark off? It’s like their skin! As for the seed-tray, that is mine . You’ve no business taking things from the greenhouse and you know it. Now I want it back, and you’d better not have disturbed the seeds or heaven help you!”

Omri swallowed hard. He and his father stared at each other.

“I can’t give it back,” he said at last. “But I’ll buy you another tray and some more seeds. I’ve got enough money. Please .”

Omri’s father had a quick temper, especially about anything concerning the garden, but he was not unreasonable, and above all he was not the sort to pry into his children’s secrets. He realized at once that his seed-tray, as a seed-tray, was lost to him forever and that it was no use hectoring Omri about it.

“All right,” he said. “You can go to the hardware shop and buy them, but I want them today.”

Omri’s face fell.

“Today? But it’s nearly five o’clock now.”

“Precisely. Be off.”

Omri was not allowed to ride his bicycle in the road, but then he wasn’t supposed to ride it on the pavement either, not fast at any rate, so he compromised. He rode it slowly on the pavement as far as the corner, then bumped down off the curb and went like the wind.

The hardware shop was still open. He bought the seed-tray and the seeds and was just paying for them when he noticed something. On the seed packet, under the word ‘Marrow’ was written another word in brackets: ‘Squash’.

So one of the ‘Three Sisters’ was marrow! On impulse he asked the shopkeeper, “Do you know what maize is?”

“Maize, son? That’s sweetcorn, isn’t it?”

“Have you some seeds of that?”

Outside, standing by Omri’s bike, was Patrick.

“Hi.”

“Hi. I saw you going in. What did you get?”

Omri showed him.

“More presents for the Indian?” Patrick asked sarcastically.

“Well, sort of. If—”

“If what?”

“If I can keep him long enough. Till they grow.”

Patrick stared at him and Omri stared back.

“I’ve been to Yapp’s,” said Patrick. “I bought you something.”

“Yeah? What?” asked Omri, hopefully.

Slowy Patrick took his hand out of his pocket, held it in front of him and opened the fingers. In his palm lay a cowboy on a horse, with a pistol in one hand pointing upward, or what would have been upward if it hadn’t been lying on its side.

Omri looked at it silently. Then he shook his head.

“I’m sorry. I don’t want it.”

“Why not? Now you can play a proper game with the Indian.”

“They’d fight.”

“Isn’t that the whole idea?”

“They might hurt each other.”

There was a pause, and then Patrick leant forward and asked, very slowly and loudly, “ How can they hurt each other? They are made of plastic !”

“Listen,” said Omri, and then stopped, and then started again. “The Indian isn’t plastic. He’s real.”

Patrick heaved a deep, deep sigh and put the cowboy back in his pocket. He’d been friends with Omri for years, ever since they’d started school. They knew each other very well. Just as Patrick knew when Omri was lying, he also knew when he wasn’t. The only trouble was that this was a non-lie he couldn’t believe.

“I want to see him,” he said.

Omri debated with himself. He somehow felt that if he didn’t share his secret with Patrick, their friendship would be over. He didn’t want that. And besides, the thrill of showing his Indian to someone else was something he could not do without for much longer.

“Okay. Come on.”

Going home they broke the law even more, riding on the road and with Patrick on the crossbar. They went round the back way by the alley in case anyone happened to be looking out of a window.

Omri said, “He wants a fire. I suppose we can’t make one indoors.”

“You could, on a tin plate, like for indoor fireworks,” said Patrick.

Omri looked at him.

“Let’s collect some twigs.”

Patrick picked up a twig about a foot long. Omri laughed.

“That’s no good! They’ve got to be tiny twigs. Like this.” And he picked some slivers off the privet hedge.

“Does he want the fire to cook on?” asked Patrick slowly.

“Yes.”

“Then that’s no use. A fire made of those would burn out in a couple of seconds.”

Omri hadn’t thought of that.

“What you need,” said Patrick, “is a little ball of tar. That burns for ages. And you could put the twigs on top to look like a real campfire.”

“That’s a brilliant idea!”

“I know where they’ve been tarring a road, too,” said Patrick.

“Come on, let’s go.”

“No.”

“Why not?”

“I don’t believe in him yet. I want to see.”

“All right. But first I have to give this stuff to my dad.”

There was a further delay when his father at first insisted on Omri filling the seed-tray with compost and planting the seeds in it then and there. But when Omri gave him the corn seed as a present he said, “Well! Thanks. Oh, all right, I can see you’re bursting to get away. You can do the planting tomorrow before school.”

Читать дальше