Julia presided over an unlikely irruption of bohemianism on this islet. ‘Everybody is either a genius or a painter or peculiar in some way,’ complained one visitor, ‘is there nobody commonplace?’ With its perpetual parties and play-acting, Freshwater was one long performance, and Dimbola its proscenium arch. Such was the throng of art and letters that one writer compared it ‘to Athens in the time of Pericles, as being the place to which all the famous men of the reign of Queen Victoria gravitated’; another considered its society closer to a French salon than any English gathering.

It’s hard to imagine now that this sleepy village should have been filled with such fanciful displays. Leaving Dimbola and its eccentric cast behind, I push my bike up the hill – and nearly blunder into a skylark at my feet. Ahead of me, the island rises, ‘walled up from the ocean by a bulwark of immense cliffs’, as Adams writes, caught up in the spirit of the sublime. ‘A mighty barrier, truly! but yet not altogether impregnable against the assaults of the sea. Their glittering sides are strangely branded, as it were, by dark parallel lines of flint, that score the surface of the rock from misty ridge to spray-beaten base. Huge caverns penetrate into their recesses. Isolated rocks frown all apart in gloomy grandeur. Immense chasms yawn …’

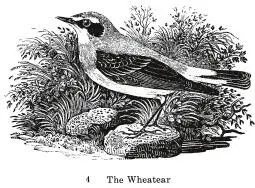

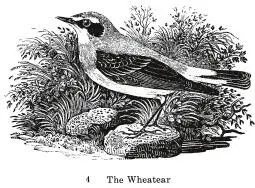

Couched in such breathless terms, the terrain takes on the air of Julia’s amateur dramatics: the celadon sea, the lime-lit cliffs, the sun switched on and off by a shifting curtain of clouds; a Victorian stage on which an over-made-up Edgar might be telling his blinded father Gloucester, ‘How fearful/And dizzy ’tis to cast one’s eyes so low!’ This is a place used and shaped by every species that visits it. The turf is as clipped as a bowling green, the work of rabbits whose burrows riddle the soft chalk. Violets and gentians stud the grass like purple stars. There’s barbarity here too, invoked by a raven perched on the edge, but it is upstaged by an altogether more diminutive bird: the wheatear, newly arrived from the other end of the earth.

I say wheatear, but that is a prudish corruption of its wonderfully common name, white arse, one which reaches back to the Old English hwīt , and ærs , its distinctive tail. Its binomial, Oenanthe oenanthe , is almost bigger than the bird itself, and derives from the Greek for wine flower, since its bearer’s arrival in southern Europe from Africa coincides with the blossoming of the vines. Weighing barely twenty-five grams, the northern wheatear accomplishes a migration among the greatest of any songbird, round trips of up to eighteen thousand miles from South Africa to Alaska. Those that land in southern England, however, choose to nest here, using abandoned burrows.

Under the cover of a hollow created by subsidence, I crawl along to get a better look. They’re exquisite birds. I focus on one male as it hops about on the precipice. Its bluish-grey back reminds me of a guardsman’s greatcoat, and its pale belly is blushed with a seductive peach tint. Its face is pharaonically masked by a black eye stripe. It stands on an outcrop of chalk, proud and alert on surprisingly long legs, the light reflecting up at its breast. As it runs along, it launches into short skittering flights, flaunting its white arse. It is loyal to the downs, a welcome resting place after all those thousands of air-miles, but a fateful choice for its predecessors, which were rewarded for their efforts by being baked in a pie.

According to Gilbert White, writing in the 1770s, wheatear (as a respectable cleric, he was bound to use the bird’s less indecorous name) were ‘esteemed an elegant dish’. ‘At the time of the wheat-harvest they begin to be taken in great numbers; are sent for sale to Brighthelmstone and Tunbridge ; and appear at all the tables of the gentry that entertain with any degree of elegance.’

To supply such slender fare, shepherds left their flocks every summer – to the annoyance of their employers – setting their snares on the feast of St James, 25 July. Thomas Bewick, writing two decades after White and referring, in his no-nonsense northern text, to the White-Rump, noted that the traps were made of horse hair, and hidden beneath a piece of turf. He reckoned ‘near 2000 dozen’ were taken each year around Eastbourne alone, to be sold for sixpence a dozen in London, ‘where they are … thought not inferior to Ortolan’, a small bird which was and still is eaten in France. (A captive ortolan’s eyes were poked out; it was then force-fed oats before being drowned in brandy and swallowed beak-first, its carcase covered with a napkin to hide the shameful act from the eyes of God.) In 1825, Mrs Mary Trimmer, ‘author of Man in a Savage and Civilized State ’, updated Bewick’s book, silently removing ‘White-Rump’ from its chapter heading, adding that, ‘as they are very timid birds, the motion of even a cloud … will immediately drive them into the traps’, and noting that a single shepherd could catch eighty-four dozen birds a day.

As the overfed inhabitants of the watering holes of Brighton and Tunbridge Wells, themselves as migratory as the birds, sucked and chewed one white arse after another, it is little wonder that, as the Reverend White noted, ‘About Michelmas they retire and are seen no more until March .’ White, though, had no idea where they went.

They may be scared by clouds, but wheatear are bold birds, hopping close to my feet. To Derek Jarman, walking in Dungeness where he had retreated to his tar-black Prospect Cottage, and where he gathered holy stones for friends to wear around their necks as though to protect them from the nearby nuclear reactor, ‘the snobbish wheatears complain – tch! tch! ’ But Tennyson heard them differently –

The wheatears whisper to each other:

What is it they say? What do they there?

– as he pounded the island’s downs in his military cape and broad-brimmed hat and oath-catching beard.

Tennyson was born in Lincolnshire in 1809. ‘Before I could read,’ he remembered, ‘I was in the habit on a stormy day of spreading my arms to the wind, and crying out “I hear a voice that’s speaking in the wind.”’ He was a poet attuned to nature in what we consider to have been an age of science and industry. Yet the era itself was wild and prophetic, as filled with female Christs and millenarians as it was with evolutionists and industrialists; as much concerned with myth and mortality and looking backwards as it was with moving into the future.

Tennyson’s most famous work, In Memoriam , was a tribute to his handsome young friend Arthur Hallam, for whom he had ‘a profound affection’ and who died of a cerebral haemorrhage at the age of twenty-two:

Forgive my grief for one removed,

Thy creature, whom I found so fair.

When the poem was published in 1850, many readers thought these lines must have been written by a woman. To Tennyson, Hallam had become conflated with the young hero of Thomas Malory’s Morte d’Arthur , the inspiration for his own Idylls of the King , which in turn Julia Margaret Cameron re-imagined in her dreamy photographs. Their Isle of Wight was a new Albion, clad in its white cliffs, as if its downs and beaches were a concentration of all that Britain represented. After all, the entire empire was overseen from this sliver of southern England, floating in the Channel like Lyonesse, the mythic isle where Arthur was said to have died. A few miles from Freshwater, in her island fastness of Osborne, Victoria, who would lose her own prince to typhoid, pronounced the poem to be her favourite work of literature after the Bible.

Читать дальше