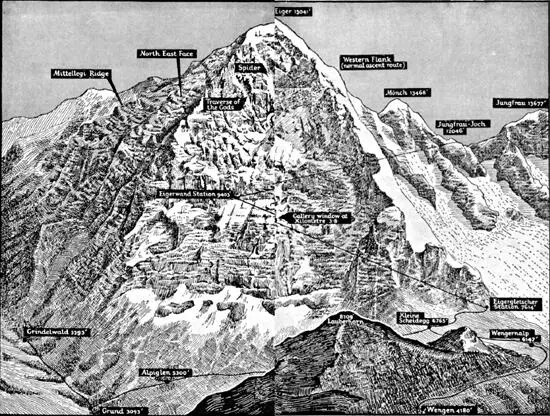

The White Spider is at once the most exciting and compulsively gripping of books and at the same time repellent and disturbing. Heroic in scale, legendary in the stories of long-lost lives that it recounts, it allows readers to experience vicariously the terror and the exultation of mountaineering from the warm comfort of their armchairs. It leaves you with a haunted sense of wonder. As you close the book you are confused by the life-enhancing delight of climbing that shines through stories of the most appalling human experiences. It leaves you filled with apprehension and wondering what it would be like to be up there on the forbidding fastness of that storm-lashed face.

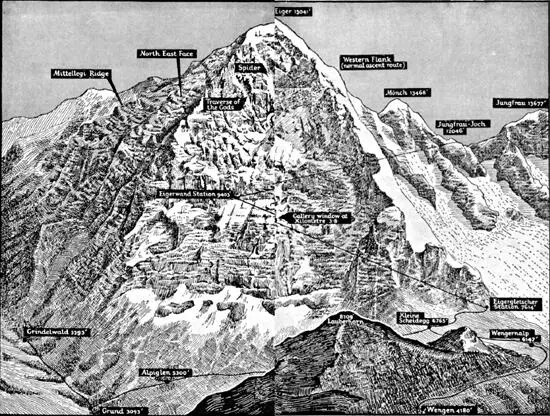

Harrer writes about the aura of fatality of the Eiger’s North Face and of the ‘hunted’ feeling that climbers experience on the climb. The grim history lies scattered all around. Broken pitons, the shattered rocks strewn with the debris of past ascents, torn rucksacks, tattered ropes drifting in the wind, indistinguishable scraps of colour-drained clothing, the unshakable sense of other people’s tragedies found in lonely spots all over the face. I had always been haunted by the North Face of the Eiger.

In September 2000, when Ray Delaney and I made our first attempt on the 1938 route, it was less a climb and more a pilgrimage in the footsteps of our heroes. It was exciting and frightening and loaded with the psychological baggage of all that we knew about it. We too felt that hunted sensation as we mutely witnessed the deaths of two young men, then crept, cowed and haunted, back to the safety of the valley. We tried again during the following two summers, beaten back each time by foul weather and cold, uncomfortable bivouacs. Today we still think about returning to this seminal mountain to complete our farewell ascent to a lifetime of mountaineering that was inspired, for me at least, almost entirely by reading The White Spider.

One successful ascensionist described his time on the face: ‘I seemed to have been in a dreamland; not a dreamland of rich enjoyment, but a much more beautiful land where burning desires were translated into deeds.’ That to me was inspirational. The words of an intelligent, sensitive man who had ‘in complete harmony … a perfectly fashioned body, a bright, courageous mind and a receptive spirit’. A man who thought that sometimes in life it was worth gambling far more than you could ever possibly win.

Joe Simpson

Sheffield

September 2004

Joe Simpson is the author of Touching the Void and The Beckoning Silence.

“Come back safe, my friends”

“WRITING a book about the North Face of the Eiger? Whatever for?” The question was put to me by a man of some standing in Alpine circles. I was taken aback and slightly cross, so I gave him a somewhat off-hand answer: “For people to read, of course.”

That started him off on a passionate tirade.

“Who’s likely to read it? Don’t you think the handful of climbers who are really interested in that crazy venture have had quite enough literature on the subject already? Or do you just want to join the sensation-mongers, from whose ranks a serious climber like yourself should keep as remote as possible?”

I answered him: “If all climbers shared your point of view, it wouldn’t be surprising to find the newspaper reports overflowing with misstatements and exaggerations. I believe the public has a right to authoritative information, especially when mountaineering problems become human ones. And I think it is a climber’s duty to contribute to the formation of public opinion in such matters.”

And with that I dropped the unpleasant argument.

However, he had failed to shake my purpose to write a book about the Eiger. I had already been engaged on the preliminary work for months, indeed for years. My home was piled high with books, periodicals, newspaper-cuttings—about two thousand of them in various languages—on the subject of the Eiger’s North Face. I had written, and received replies to, innumerable letters. Every letter from a climber who had actually done the North Face was a personal document and, more than that, the documentation of a personality. I had no intention of allowing the History of the Eiger’s North Face to become a mere calendar of climbs, its foreground theme was to be the men who had done those climbs.

This man, who was so shocked at the idea of my writing a book about the North Face of the Eiger, was akin to a certain type of climber, who plants himself on a pedestal of extreme exaltation and merely smiles superciliously at the nonsensical idea of writing for the layman about climbing. But one cannot ignore public opinion and at the same time expect it to judge one sympathetically and intelligently.

No less an authority than the late Geoffrey Winthrop Young, one of the Grand Old Men of British climbing and outstanding in its literature, recognised the demands of the age and dealt with them in his article “Courage and Mountain Writing”. 1 He understood well enough the general public’s thirst for sensation, but he faced it squarely and yet refused to give in to it.

“The modern lay-public,” he writes, “is now ready to read mountain adventures among its other sensational reading. It still demands excitement all the time. The cut rope is no longer essential, and the blonde heroine has less appeal, now that she has to climb in nailed boots and slacks. It wants records, above all. Records in height, records in endurance, hair-breadth escapes on record rock walls, and a seasoning of injuries, blizzards, losses of limbs and hazards of life…. I have suggested that the writers and producers of mountain books must also take some of the responsibility….”

Responsibility with regard to the subject-matter—responsibility with regard to the wishes of the reader. The key to a proper comprehension and understanding between the layman and the climber may well lie here.

And how is the climber to write? In Young’s view: “If he is to be read by human beings, he must write his adventures exactly as he himself humanly saw them at the time. General or objective description, such as satisfied the slower timing of the last two centuries, now reads too slowly, and is dull.”

But how can he avoid becoming a positive bore, if he intends to write a whole book about a single Alpine mountain-face and the solitary route up it? Once again I will quote Young: “However well-known the peak, or the line of ascent, no mountain story need ever repeat itself, or seem monotonous. Both mountain surface and mountain climber vary from year to year, even from day to day.”

There is no mountain, no mountain-face anywhere, of which that can more truly be said than of the Eiger and its North Face. And all the men concerned—those who succeeded, or those who tried and failed—were all sharply defined personalities. No two of them were alike.

“A book about the Eiger? Whatever for?”

The question continued to rankle, though probably the man who asked it never intended to make me angry. Yet the barb persisted. And, though I needed neither an explanation nor a justification for my undertaking, I was greatly heartened to read the following words in an article by Albert Eggler, the well-known Alpine climber and leader of the Swiss Everest Expedition of 1956: “However, we Westerners more especially, who owe the improvements of our lifetime to the selfless devotion of a few exceptionally courageous and probably highly zealous men, ought not to be too hard on people who take on an assignment which in the end proves too big for them. Men who take unusual risks are not by any means the worst types. But what we could and should do is to open the eyes of young climbers in appropriate fashion to the very special dangers of the mountains. And in this direction, a great and worth-while duty still lies before the Alpine clubs and Alpine publications generally.”

Читать дальше