This one is for two strong women:

Joan Joffe Hall and Shirley Woodka

You see a man

trying to think.

You want to say

to everything:

Keep off! Give him room!

But you only watch,

terrified

the old consolations

will get him at last

like a fish

half-dead from flopping

and almost crawling

across the shingle

almost breathing

the raw, agonizing

air

till a wave

pulls it back blind into the triumphant

sea.

—Adrienne Rich

Table of Contents

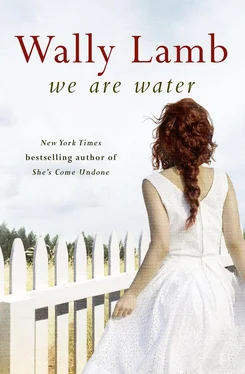

Cover

Title Page

Dedication This one is for two strong women: Joan Joffe Hall and Shirley Woodka

Epigraph Ghost of a Chance You see a man trying to think. You want to say to everything: Keep off! Give him room! But you only watch, terrified the old consolations will get him at last like a fish half-dead from flopping and almost crawling across the shingle almost breathing the raw, agonizing air till a wave pulls it back blind into the triumphant sea. —Adrienne Rich

Prologue Prologue

Gualtiero Agnello

Part I: Art and Service

Chapter One: Annie Oh

Chapter Two: Orion Oh

Chapter Three: Annie Oh

Chapter Four: Orion Oh

Chapter Five: Annie Oh

Chapter Six: Orion Oh

Chapter Seven: Annie Oh

Chapter Eight: Orion Oh

Chapter Nine: Annie Oh

Part II: Mercy

Chapter Ten: Ruth Fletcher

Part III: Family

Chapter Eleven: Andrew Oh

Chapter Twelve: Marissa Oh

Chapter Thirteen: Ariane Oh

Chapter Fourteen: Orion Oh

Chapter Fifteen: Andrew Oh

Chapter Sixteen: Orion Oh

Chapter Seventeen: Andrew Oh

Chapter Eighteen: Orion Oh

Part IV: A Wedding

Chapter Nineteen: Kent Kelly

Chapter Twenty: Annie Oh

Chapter Twenty-One: Kent Kelly

Chapter Twenty-Two: Annie Oh

Chapter Twenty-Three: Kent Kelly

Chapter Twenty-Four: Andrew Oh

Chapter Twenty-Five: Annie Oh

Chapter Twenty-Six: Andrew Oh

Part V: Three Years Later

Chapter Twenty-Seven: Orion Oh

Chapter Twenty-Eight: Orion Oh

Chapter Twenty-Nine: Orion Oh

Gratitude

A Note from Wally Lamb

About the Author

Also by Wally Lamb

Copyright

About the Publisher

Rope-Skipping Girl

Gualtiero Agnello

August 2009

I understand there was some controversy about the coroner’s ruling concerning Josephus Jones’s death. What do you think, Mr. Agnello? Did he die accidentally or was he murdered?”

“Murdered? I can’t really say for sure, Miss Arnofsky, but I have my suspicions. The black community was convinced that’s what it was. Two Negro brothers living down at that cottage with a white woman? That would have been intolerable for some people back then.”

“White people, you mean.”

“Yes, that’s right. When I got the job as director of the Statler Museum and moved my family to Three Rivers, I remember being surprised by the rumors that a chapter of the Ku Klux Klan was active here. And it’s always seemed unlikely to me that Joe Jones would have tripped and fallen headfirst into a narrow well that he would have been very much aware of. A well that he would have drawn water from, after all. But if a crime had been committed, it was never investigated as such. So who’s to say? The only thing I was sure of was that Joe was a uniquely talented painter. Unfortunately, I was the only one at the time who could see that. Of course now, long after his death, the art world has caught up with his brilliance and made him highly collectible. It’s sad—tragic, really. There’s no telling what he might have achieved if he had lived into his forties and fifties. But that was not to be.”

I’m upstairs in my studio, talking to this curly-haired, pear-shaped Patrice Arnofsky. When she called last week, she’d explained that she was a writer for an occasional series which profiled the state’s prominent artists in Connecticut magazine. They had already run stories on Sol LeWitt, Paul Cadmus, and the illustrator Wendell Minor, she said. Now she’d been assigned a posthumous profile of Josephus Jones in conjunction with a show that was opening at the American Folk Art Museum. “I understand that you were the only curator in his lifetime to have awarded him a show of his work,” she’d said. I’d told her that was correct. Agreed to talk with her about my remembrances of Joe. And so, a week later, here we are.

Miss Arnofsky checks the little tape recorder she’s brought along to the interview and asks me how I met Josephus Jones.

“I first laid eyes on Joe in the spring of 1957 when he appeared at the opening of an exhibition I had mounted called ‘Nineteenth-Century Maritime New England.’ It was a pretentious title for a self-congratulatory concept—a show that had been commissioned by a wealthy Three Rivers collector of maritime art whose grandfather had made millions in oceanic shipping. He had compensated the museum quite generously for my curatorial work, but it had bored me to tears to hang that show: all those paintings of frigates, brigs, and steamships at sea, all that glorification of war and money.

“On the afternoon of the opening, I was making small talk with Marietta Colson, president of the Friends of the Statler, when she stopped midconversation and looked over my shoulder. A frown came over her face. ‘Well, well, what have we here?’ she said. ‘Trouble?’ My eyes followed hers to the far end of the gallery, and there was Jones. Among the well-heeled, silver-haired patrons who had come to the opening, he was an anomaly with his mahogany skin and flattened nose, his powerful laborer’s build and laborer’s overalls.

“We watched him, Marietta and I, as he wandered from painting to painting. He was carrying a large cardboard box in front of him, and perhaps that was why he reminded me of the gift-bearing Abyssinian king immortalized in The Adoration of the Magi —not the famous Gentile da Fabriano painting but the later one by Albrecht Dürer, who, to splendid effect, had incorporated the classicism of the Italian Renaissance in his northern European art. Do you know that work?”

“I know Dürer, but not that painting specifically. But go on.”

“Well, throughout the gallery, conversations stopped and heads turned toward Josephus. ‘I hope there’s nothing menacing in that box he’s holding,’ Marietta said. ‘Do you think we should notify the police?’ I shook my head and walked toward him.

“He was standing before a large Caulkins oil of La Amistad , the schooner that had transported African slaves to Cuba. The painting depicted the slaves’ revolt against their captors. ‘Welcome,’ I said. ‘You have a good eye. This is the best painting in the show.’

“He told me he liked pictures that told a story. ‘Ah yes, narrative paintings,’ I said. ‘I’m drawn to them, too.’ His bushy hair and eyebrows were gray with cement dust, and the bib of his overalls was streaked with dirt and stained with paint. He had trouble making eye contact. Why had he come?

“‘I paint pictures, too,’ he said. ‘I can’t help it.’ I knew what he meant, of course. Had I not been painting for decades, more in voluntarily than voluntarily at times? ‘I’m Gualtiero Agnello, the director of this museum,’ I said, holding out my hand. ‘And you are?’

Читать дальше