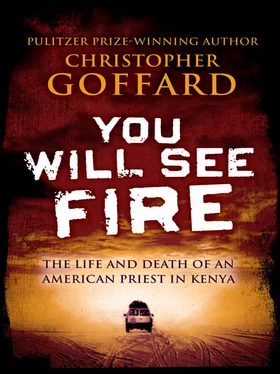

Everybody in the area knew the American priest, and many depended on him for food and school fees; they would surround him as soon as he pulled up to a cluster of huts or to the little brick schools or churches. By the side of the road, in the shade of eucalyptus trees, he bowed his head and listened to their confessions Конец ознакомительного фрагмента. Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес». Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес. Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

. I have stolen a cow, Father. I have slept with girls, Father. I have struck my wife, Father. So much of his knowledge about the country had arrived in this fashion; the chronicle of sins formed an infinitely more accurate barometer of the country’s soul than did the Nairobi newspapers.

With luck, he would be home before nightfall. The road bristled with bandits, or shifta, and the sun didn’t linger on the horizon. It was nothing like the protracted twilights of his Minnesota childhood—that long dream hour of crying cicadas and droning mosquitoes. Here near the equator, night scythed down as swiftly as a panga knife; one writer compared the experience to having a sack pulled over your head Конец ознакомительного фрагмента. Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес». Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес. Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

.

The shotgun would stay with him as he walked the grounds at night, locking the church, shuttering the windows of his home, double-checking the locks; it stayed with him as he walked down the long, shadowed hallway to his room, the last on the left. Scattered before him at his desk, dimly illuminated by generator light, were dangerous documents. They told the story of the secret history of his adopted country, a subterranean narrative of land and blood. They chronicled the sins of Kenya’s rulers—decades of land-stealing, ethnic carnage, rape. There were affidavits from peasant farmers, land deeds, newspaper clips, correspondence, accounts from local girls. He had been collecting them for years. He spent hours in his room, reading, poring over documents, making notes in his journal. For some time, he’d been anticipating his violent death, warning friends and family in the States to expect it.

For most of his career as a bush missionary, save for the church and the tribes he had lived among, few in Kenya had known his name. He had done a fair job of impersonating the other good, hardworking, politically impassive men of Christ. He had raised little noise outside the Church, with the rationalization that he had plenty of God’s work to keep him busy. Then, no longer young or even middle-aged, he’d become chaplain at a hillside displacement camp called Maela, where he witnessed a scale of misery that nothing had prepared him for—ubiquitous choking dust, mud, disease, burned skin sloughing off children’s hands like gloves, and then the government’s nighttime raid on the camp. Good Lord, some of the refugees had even been singing as they were crammed onto trucks to be scattered across the countryside, singing because they’d actually believed the president’s promise that he would find them land. That six-month experience—culminating in his own beating and banishment from the camp—had forced him to reexamine his silence. Some of the lightness went out of him; photos showed a depth of sadness shadowing his eyes after that.

It would have been possible, even then, for him to melt back into his missionary work. His bishop, whose mantra was “Don’t provoke,” had sent him to the house in Masailand at the country’s southwest edge—about as far as he could go without spilling into Tanzania—with the hope that the remoteness would keep him out of trouble. The bishop had been mistaken. It had not deterred Kaiser from appearing at the Akiwumi Commission—a tribunal launched by President Moi, with the ostensible goal of probing the causes of the tribal clashes that had killed more than one thousand people in recent years. The real purpose, many suspected from the start, was to conceal the government’s central role in the carnage. Kaiser had been warned against speaking. His bishop believed the tribunal a waste of time, and Kaiser’s intention to name names a pointless provocation.

Some African churchmen considered it an embarrassment that a white man should presume to lecture them about their affairs. The missionary’s role in Kenyan history had been a fraught one. Determined to bring pagans of the Dark Continent into the Christian fold, the early missionaries preached not just salvation but also the superiority of white civilization. Many of Africa’s independence leaders, including Kenya’s, had been products of missionary educations. But it was easy for Africans to view the missionary legions with ambivalence, if not outright hostility. They had built schools but taught Africans to hate themselves. The Church had been a spearpoint of the colonial land grab, legitimizing the conquest, and had sided with the British against the Mau Mau uprising of the 1950s, defining the struggle as one of light versus darkness, God versus Satan. Jomo Kenyatta, Kenya’s first president, had put it this way: “ When the missionaries arrived, the Africans had the land Конец ознакомительного фрагмента. Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес». Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес. Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

and the missionaries had the Bible. They taught us to pray with our eyes closed. When we opened them, they had the land and we had the Bible.” Kaiser had inherited this uneasy legacy. For many of his colleagues, guilt fostered paralysis and passivity—a feeling that African politics was best left to Africans, lest the Church be accused of reproducing its past sins.

Yet Kaiser had gone to the tribunal, braving the bad roads, waiting in the makeshift courtroom in his ironed clerical blacks, with his neck brace and his Roman collar and a folder of documents. Up he walked, a broad-shouldered, long-limbed man with a loose, slightly bandy-legged gait and thinning white hair. He was not a churchman of rank, not a bishop or a nuncio, not even the priest of a politically important parish like Nairobi. He was, up until then, a man of small importance to history—just a bullheaded old mazungu from one of the country’s poorer corners.

Читать дальше