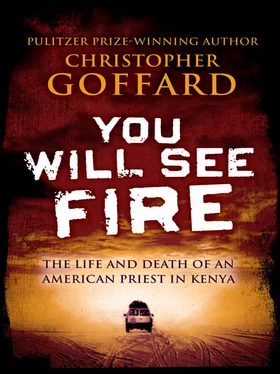

In the weeks that followed Kaiser’s death, he would make discreet inquiries, trying to retrace the priest’s final steps. Mostly, though, he waited. It might not be necessary for him to get involved.

The case felt coldly familiar to Gathenji in a personal way. His father, a Presbyterian evangelist, had been the victim of a politically charged slaying in September 1969, dragged from his home by fellow Kikuyus for refusing to swear an oath of tribal loyalty.

Gathenji, a twenty-year-old student at the time, believed the attack was sanctioned by elements of the Kikuyu-dominated government of Kenya’s first president, Jomo Kenyatta. No one had ever been punished for his death; there had been no trial, and nothing resembling a real investigation. The experience, more than any other factor, had pushed the young Gathenji into a career in the law, which he perceived as a process—at its best—of ferreting truth from darkness and lending strength to the helpless. He had developed an abiding wariness and a deep-seated distrust of institutions, including ecclesiastical ones.

Charles Mbuthi Gathenji. For the Kenyan attorney who lost his father as a young man, Kaiser’s death had personal echoes. Photograph by Carolyn Cole. Copyright 2009, Los Angeles Times. Reprinted with permission.

Like Kaiser, Gathenji’s father had been an inveterate builder and a tough former soldier who had ignored reported warnings to adopt a more compromising stance. He had suspected that his betrayer would likely be a friend, a church mate, someone scared enough to sell him out.

Kaiser had been aware of the story of Gathenji’s father, of course. During one of their last meetings, the harried priest had invoked the lawyer’s father as a reminder of what they were both fighting for.

Both deaths had had a feeling of inevitability. Both of the dead had seen it coming, clear-eyed, from a great distance.

HE ARRIVED IN December 1964, stepping off a freighter into the harsh equatorial sunlight at Kenya’s eastern port of Mombasa, into a country that had just reeled exuberantly through its first year of independence from the British. Across the continent, the apparatus of European domination was being shuffled off, with varying degrees of violence, and the sense of possibility was unbounded. Kaiser was thirty-two years old and just ordained, fair-skinned and squared-jawed, a big-framed man with an army duffel bag under a thick arm. He boarded a prop plane, which carried him over the vast bulge of land toward his first parish in western Kenya. It was his first sight of the country in which he would spend most of his life—the great forests and maize farms and tea plantations, the ice-capped towers of Mount Kenya, the staggering cleft of the Great Rift Valley.

Kaiser’s early years in Kenya seem to have reflected the country’s own mood of hope and possibility. He lived in a cool, high region of softly sloping green hills dotted with huts and little granaries and covered with groves of black wattle trees, eucalyptus, and cypress, grass pastures, and terraced fields. This was the land of the Kisii, or Abagusii, a place the British had declared off-limits to European settlers.

Crowds swarmed to meet the missionary as he settled into a parish with eighteen thousand baptized Catholics and eighteen Catholic schools. Winds from Lake Victoria rustled maize rows that soared above a tall man’s head, and from the high hills of Kisiiland he could glimpse the great gulf. Families tended small farms called shambas, growing tea and coffee, as well as sweet potatoes, finger millet, and corn. Along the narrow dirt roads Конец ознакомительного фрагмента. Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес». Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес. Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

the women toted heavy kerosene tins of corn kernels to the power mills. Sclerotic little buses called matatus raced by helter-skelter; frequent rains stalled them in thick, impassable mud.

English and Swahili were of limited use here. The Kisii, isolated in the hills for two hundred years, were Bantu speakers whose language was grasped by few outsiders. There were no dictionaries or written grammatical rules. Kaiser set to work mastering the language, and after four months he was conversant enough to hear confessions.

The Kisii were fond of late-afternoon drinking parties, and men clustered together on stools, thrusting three-foot-long bamboo drinking tubes into pots of boiling, gruel-thick beer made of fermented millet and maize flour. The sociable Minnesota priest, invited to partake, confided to friends that he found it awful-tasting but learned how to fake a sip.

John Kaiser during his first years in Kenya, in the 1960s. He lived among the Kisii in the fertile highlands of western Kenya. A stout six foot two, he built churches across the countryside, quick, crude structures of red earth and river-bottom sand, and went up ladders with pockets stuffed with bricks. Photograph courtesy of the Kaiser family.

The huts were windowless, with walls of mud and wattle. All night during the cold months, upward through fissures in the tight grass thatching of the high-coned roofs, filigrees of smoke curled from hearth fires where families huddled, asleep on cowhides scattered across floors of dried mud and dung.

On some levels, the area was as foreign to Kaiser’s native Midwest as it is possible to conceive. Despite the presence of Catholics and Seventh-Day Adventists, most Kisii remained animists steeped in traditional practices. Polygamy was ubiquitous. For a man, the highest ambitions were abundant offspring—the only insurance of personal immortality—and multiple wives, each with her own hut, between which he would rotate. Fecundity was celebrated, the ultimate badge of a woman’s worth, and she was expected to give birth every two years while it was biologically possible. Giving birth to fifteen children was common. The Kisii birthrate, one of the world’s highest, was to Kaiser “a great sign of Divine favour.” Конец ознакомительного фрагмента. Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес». Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес. Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Population control he regarded as evil. In Kisiiland, a pregnant woman did not speak of her pregnancy for fear she would appear boastful and invite malevolent envy. Any perceived advantage, in fact, invited envy and witchcraft.

“No one dies without carrying someone on his back,” went one proverb. This reflected a dark vision of invisible forces harrying people to their graves. Everything required a cause, an explanation, especially major calamities. Rancor between co-wives was a given, and a woman who found herself infertile, or who lost a child during pregnancy, inevitably suspected some machination of the women who shared her husband. The wealthy lived in fear of the poor; the poor lived in fear of the very poor; the very poor lived in fear of the wretched. It was understood that for the powerless, the jealous, and the angry, there was no recourse except through magic, and so the community’s most miserable and reviled members—childless, neglected old women, for instance—were often the most feared and vulnerable to murder. The killing of accused witches was common.

Читать дальше