Caroline’s outburst said as much about her future prospects as her present unhappiness. Her husband had demonstrated in the most painful way possible that he lacked her capacity both for deep feeling and for consistent, considered action. It was not that George did not love his daughters – he was genuinely distressed by their absence, and felt the loss of their company – but he was not prepared to sacrifice all his interests on their behalf. Nor, much as he loved his wife, would he allow her openly to dictate how he should behave in the public sphere. It was a hard lesson that Caroline took much to heart. Even on matters that touched them in the very core of their being, the prince could not necessarily be depended upon to do either the right or the politic thing. That did not make her abandon the partnership to which she had committed when she married him, but she was compelled to accept that what could not be achieved by the open alliance of equals might be much better delivered by management and manipulation.

The king expressed a similar view when the reconciliation was finally achieved, and the prince was formally received by his father in a ceremony that reminded Lady Cowper of ‘two armies in battle array’. George I saw his son privately for only a painful ten minutes, but devoted over an hour to haranguing his daughter-in-law on her failures. ‘She could have made the prince better if she would,’ he declared; and he hoped she would do so from now on. Caroline had reached much the same conclusion. For the next twenty years, she did all she could to ensure that her husband was encouraged and persuaded to follow paths that she believed served the best interests of their crown. By the time Lord Hervey watched her do it, she had turned it into a fine art. ‘She knew … how to instil her own sentiments, whilst she affected to receive His Majesty’s; she could appear convinced whilst she was controverting, and obedient when she was ruling; by this means, her dexterity and address made it impossible for anybody to persuade him what was truly the case, and that while she was seemingly in every occasion giving up her opinion to his, she was always in reality turning his opinion and bending his will to hers.’ 53

In one sense, it was not an unsuccessful policy. Her patience and self-effacement ensured that Caroline was able to achieve much of what she wanted in her management of her husband. Above all, she preserved the unity of their partnership. Throughout all their tribulations, in private and in public, she strained every sinew to prevent any permanent rupture dividing them. Whether the threat came from a discontented father, a predatory mistress, an unsatisfactory child, or a potentially disruptive politician, Caroline devoted all her skills to neutralising any possibility of a serious breach between them. It was clear to her that they were infinitely stronger as a like-minded couple than as competing individuals who would inevitably become the focus for antagonistic and destructive opposition. But although in later years she took some pride in the tireless efforts she had directed to maintaining their solidarity, she was aware that it had not been achieved without cost. To be locked into a pattern of perpetual cozening and cajolery was wounding and exhausting for her and demeaning for her husband. It kept them together; but it was not the best foundation upon which to base a marriage. In the end, despite the strength of the feelings that united them, both she and George were, in their different ways, warped and belittled by it.

As Caroline had feared, her elder daughters were never restored to her while the old king lived. She went on to have other children: William in 1721, Mary in 1723 and finally Louisa in 1724. But it was not until George I died, in 1727, from a stroke suffered while travelling through the German countryside he loved, that Anne, Amelia and Caroline came back to live with their parents again. By then it was too late to establish the stable home life that Caroline had hoped to provide for them. Before they had been taken from her, she had been a careful mother to her girls. ‘No want of care, or failure or neglect in any part of their education can be imputed to the princess,’ her husband had written in one of his many fruitless appeals to his father. 54Caroline’s daughters would never waver in their devotion to her; but their long estrangement from their father – and the constant criticism of his behaviour which they heard from their grandfather for nearly a decade – meant that on their return his eldest daughters regarded him with distinctly sceptical eyes. When they saw for themselves how he treated their mother – the strange mixture of obsession and disdain, passion and resentment, respect and rudeness, the destructive combination of warring emotions that had come to characterise George’s attitude to his wife – any tenderness they once had for him soon evaporated. It was hardly an attractive vision of domestic happiness with which to begin a new reign.

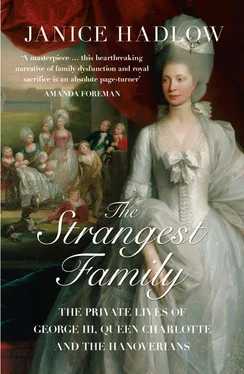

CHAPTER 2

A Passionate Partnership

GEORGE AND CAROLINE WERE AT their summer retreat at Richmond Lodge on 25 June 1727, when Robert Walpole arrived with the news of George I’s death. It was the middle of a hot day, and the royal couple were asleep; their attendants were extremely reluctant to wake them, but George was eventually persuaded to emerge from his bedroom and discover that he was now king.

It was only seven months since George’s estranged mother had died in the castle at Ahlden. Although George could never bring himself to speak about Sophia Dorothea, he did make a single gesture towards her memory that suggests much of what he felt but could not say. The day after the news arrived of his father’s death, the courtier Lady Suffolk told Walpole she was startled ‘at seeing hung up in the new queen’s dressing room a whole-length portrait of a lady in royal robes; and in the bed-chamber a half-length of the same person, neither of which Lady Suffolk had seen before’. 1The pictures were of Sophia Dorothea. Her son must have salvaged them from the general destruction of all her images ordered by his father a generation before. ‘The prince had kept them concealed, not daring to produce them in his father’s lifetime.’ Now George was king, and his mother was restored – albeit without comment – to a place of honour within the private heart of the family. Walpole heard that if she had lived long enough to witness his accession, George ‘had purposed to have brought her over and declared her queen dowager’. Her death had denied him the opportunity to release his mother from her long captivity, to act as the agent of her freedom. Perhaps it was some small satisfaction to see her image where he had been unable to see her person; it was certainly a gesture of defiance towards the man who kept her from him, and a declaration of loyalty and affection towards his mother that he had never been able to make while his father lived.

The new king and queen were crowned in October, in a typically eighteenth-century ceremony that combined grandeur with chaos. Tickets were sold in advance for the event, and small booths erected around Westminster for the selling of coffee to the anticipated crowds. 2The Swiss traveller de Saussure went to watch and noted that it took two hours for the royal procession to wend its way to the abbey. Handel’s Zadok the Priest – which would be performed at every subsequent coronation – was given its first airing in the course of the ceremony, at which George and Caroline appeared sumptuously clothed and loaded down with jewellery, some of it, as it later appeared, borrowed for the day. The choristers were not considered to have acquitted themselves well – at one point, they were heard to be singing different anthems. After the ceremony was over and the grander participants had left, de Saussure watched as a hungrier crowd moved methodically over the remains of the event, carrying away anything that could be either eaten or sold. 3

Читать дальше