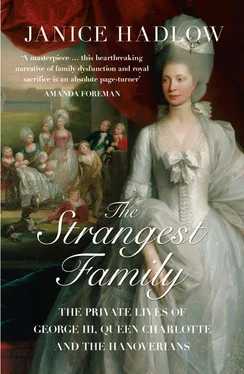

Prince George, alarmed by the escalating gravity of the situation, wrote an unequivocally submissive letter to his father, admitting that he had used those words to Newcastle, but denying that they were intended to provoke a duel and begging forgiveness. The king was unmoved; he ordered the prince to leave the palace immediately. The princess, he said, could remain only if she promised to have no further communication with her husband. He then informed the distraught couple that under no circumstances would their children leave with them. Even the newborn baby was to be left behind. ‘You are charged to say to the princess,’ declared the king to his son, ‘that it is my will that my grandson and my granddaughters are to stay at St James’s.’ 47When Caroline declined to abandon her husband, the baby prince, only a few weeks old, was taken from his mother’s arms. The couple’s daughters, aged nine, seven and five, were sent to bid their parents a formal farewell. The princess was so overwrought that she fainted; her ladies thought she was about to die.

Separated from their children and exiled from their home, the couple composed a desperate appeal to the king. It made no difference. Saying that their professions of respect and subservience were enough ‘to make him vomit’, the elder George demanded that the prince sign a formal renunciation of his children, giving them up to his guardianship. When he refused, the king deprived the prince and princess of their guard of honour, wrote to all foreign courts and embassies informing them that no one would be welcomed by him who had anything to do with his son, and ordered anyone who held posts in both his and his son’s households – from chamberlain to rat-catcher – to surrender one of them, for he would employ nobody who worked for the prince.

At St James’s, Caroline’s baby son, taken away from his mother in such distressing circumstances, suddenly fell ill. As the child grew steadily worse, the doctors called in to treat him begged the king to send for his mother. He refused to do so, until finally persuaded that if the boy died, it would reflect extremely badly on him. He relented enough to permit the princess to see her child, but with the proviso that the baby must be removed to Kensington, as he did not want her to come to St James’s. The journey proved too much for the weakened child, and before his frantic mother could get to him, he died, ‘of choking and coughing’, on 17 February 1718. In her grief, Caroline was said to have cried out that she did not believe her son had died of natural causes; but a post-mortem – admittedly undertaken by court physicians who owed their livings to the king – seemed to show that the child had a congenital weakness and could not have lived long.

The distraught parents were unable to draw any consolation from their surviving children. Their son Frederick was far away in Hanover; their daughters were closeted in St James’s, where the king, clearly thinking the situation a permanent one, had appointed the widowed Countess of Portland to look after them. They were not badly treated; but, having effectively lost both her sons, Caroline found the enforced separation from her daughters all but unbearable. The prince wrote constantly to his father, attempting to raise sympathy for his wife’s plight: ‘Pity the poor princess and suffer her not to think that the children which she shall with labour and sorrow bring into the world, if the hand of heaven spare them, are immediately to be torn from her, and instead of comforts and blessings, be made an occasion of grief and affliction to her.’ Eventually the king relented, and allowed Caroline to visit her daughters once a week; but he would not extend the same privilege to his son. ‘If the detaining of my children from me is meant as a punishment,’ the prince wrote sadly, ‘I confess it is of itself a very severe method of expressing Your Majesty’s resentment.’ 48Six months later, the prince had still been denied any opportunity to see his daughters. Missing their father as much as he missed them, the little girls picked a basket of cherries from the gardens at Kensington, and managed to send them to him with a message ‘that their hearts and thoughts were always with their dear Papa’. 49The prince was said to have wept when he received their present.

Not content with persecuting his son by dividing his family, the king also pursued him with all the legal and political tools at his disposal. When he attempted to force the prince to pay for the upkeep of the daughters he had forcibly removed from him, George sought to raise the legality of the seizure in the courts, but was assured that the law would favour the king. His father’s enmity seemed to know no rational bounds. In Berlin, the king’s sister heard gossip that he was attempting to disinherit the prince on the grounds that he was not his true child. He was certainly known to have consulted the Lord Chancellor to discover if it was possible to debar him from succeeding to the electorate of Hanover; the Chancellor thought not. This unwelcome opinion may have driven him to consider less orthodox methods of marginalising his son. Years later, when the old king was dead and Caroline was queen, she told Sir Robert Walpole that by chance she had discovered in George I’s private papers a document written by Charles Stanhope, an Undersecretary of State, which discussed a far more direct method of proceeding. The prince was ‘to be seized and Lord Berkeley will take him on board ship and convey him to any part of the world that Your Majesty shall direct’. 50Berkeley was First Lord of the Admiralty in 1717, and his family held extensive lands in Carolina. Like the Hanover disinheritance plan, it came to nothing, and relied for its veracity entirely on Caroline’s testimony; but it is a measure of the king’s angry discontent with his son that such a ludicrous scheme could seem credible, even to his hostile and embittered daughter-in-law.

When Sir Robert Walpole came to power a few years later, in 1721, relations between the king and his son’s family were still deadlocked in bitter hostility. The new first minister was convinced the situation, at once tragic and ridiculous, would have to change. Not only was it damaging to the emotional wellbeing of all those caught up in it; more worryingly, to Walpole’s detached politician’s eye, it also posed a threat to the precarious reputation of the newly installed royal house. This was not how the eighteenth century’s supreme ministerial pragmatist thought public life should be conducted; if the king and his son could not be brought to love each other, they could surely be made to see the benefits of a formal reconciliation that would ensure some degree of political calm. Walpole worked on the king with all his unparalleled powers of persuasion; he did the same with the prince, and made some progress with both. But it was Caroline who proved most resistant to his appeals. She demanded that the restoration of her children be made a condition of any public declaration of peace with her father-in-law. In the face of Walpole’s protestations that George I would never agree, and that it was better to take things step by step, she was implacable. ‘Mr Walpole,’ she assured him, ‘this is no jesting matter with me; you will hear of my complaints every day and hour and in every place if I have not my children again.’ 51

Horace Walpole thought Caroline’s ‘resolution’ was as strong as her understanding – and left to herself, it seems unlikely that she would ever have given up her demands for her children’s return – but she was undermined by the person from whom she might have expected the most support. The prince, tempted by the offer of the substantial income Walpole had squeezed out of the king, and an apparently honourable way out of the political wilderness, was prepared to compromise, and, despite his wife’s opposition, accepted terms that did not include the restitution of his daughters. He and Caroline would be allowed to visit the girls whenever they wished, but they were to remain living with their grandfather at St James’s Palace. Caroline was devastated. The courtier Lady Cowper witnessed her grief: ‘She cried and said, “I see how these things go; I must be the sufferer at last, and have no power to help myself; I can say, since the hour that I was born, that I have never lived a day without suffering.”’ 52

Читать дальше