As for the Lobster Moth, high in our beech canopy, it is a deceiver to dumbfound John le Carré. When the larva first hatches from the egg it is an ant imitator, with spindly legs that wave around a lot, and it thrashes about like an injured ant if it is disturbed. The young caterpillars are reported to defend their egg territory, and will drive off any rival caterpillar that comes too close. As they moult and grow they become both voracious leaf consumers and very odd looking – one of nature’s gargoyles. The head is larger and the legs behind it (the thoracic legs of the adult) become unnaturally attenuated even as the four pairs of legs further behind become stumpy and grasping. The back gets covered in humps, and the tail end can turn back on itself like some kind of turgid bladder, all finished off with a spike. The entire caterpillars develop a shade of pinky brown, and since they can be seventy millimetres long fully grown they are quite enough to give a shock to any casual stroller who comes across one; especially when their body is raised in the threat position with the head arched back. It is said to resemble a cooked lobster; it is certainly scary.

I wonder if all of our 150 or so moths have such complex tales to tell. The beech canopy is humming with life stories, the brambles alive with deceptions and role-playing, each crack in the bark of every tree a dark dive hiding darker narratives.

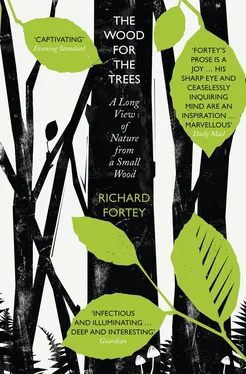

Beech

By June, the beech canopy has garnered all the light, each leaf second-guessing its neighbour at grasping any space giving on to the sky. The taller trees soar upwards for more than a hundred feet. From the ground they seem all trunk, but from the sky they seem all crown. The beech ( Fagus sylvatica ) has always been a working tree: for furniture, fire and faggots. John Evelyn’s Sylva , the first book published by the Royal Society in 1664, and the founding text of forestry, said of beech trees: ‘they will grow to a stupendous procerity, though the soil be stony and very barren: Also upon the declivities, sides, and tops of high hills, and chalky mountains especially.’ Evelyn then quotes an old rhyme:

Beech made their chests, their beds and the joyn’d-stools,

Beech made the board, the platters, and the bowls.

Three hundred years ago, beech may not have built the houses, but it did almost everything else. The management of beech trees has been the story of our wood for centuries.

In 1748, Peter Kalm, a Finnish protégé of the great Swedish botanist Linnaeus (who named the beech tree scientifically), made an informed journey through the woodlands of England. 1He observed the Chiltern lands at Little Gaddesden, a short distance from our wood over the Buckinghamshire border. Some of the trees he saw might indeed have been our own, for ‘the beeches are for many fathoms in their lower part entirely without branches, and quite smooth’. The woodsmen climbed the trees in search of squirrels (at that time red squirrels), or rooks’ nests to provide the table with squabs. They rarely used ladders; instead they strapped hideously sharp ‘crampoons’ to their feet to scale the trees, like some oversized squirrel themselves.

Kalm recorded precisely how, after felling, every part of the tree had a value; almost nothing went to waste. Farmers used to say of pigs that everything is used except the squeak; the beech woodsmen’s equivalent might be: everything has a use except the bark. They ‘sold the smooth part, or sawn it up into boards, but those of which the stem had been knotty or uneven was cut up for firewood and piled up in cords. When the beeches … were cut down and felled to the ground they were cut off close to the earth. Two or three years after that, the stump that had been left, together with all the roots proceeding from it … was dug up, cut into small pieces and arranged in four sided oblong heaps to dry … In digging up the roots they had been so careful that among those heaps there lay a great many fibres of the roots, whose length was not over 6 inches, and thickness not greater than a quill pen. These roots thus arranged were sold as fuel to those who lived some English miles around.’ Dry twigs bound into bundles of faggots were fuel for bread ovens. Some observers even regarded the beeches in the way that we now look at factory farming. The pioneering landscape architect Humphrey Repton remarked in 1803 that ‘these woods are evidently considered rather as objects of profit than of picturesque beauty’. He preferred specimen trees carrying full crowns of branches adorning a grand park, the whole designed for effect. He would not have stooped to grub up roots.

Kalm also made calculations, and his observations show a clear, scientific mind at work. ‘A beech trunk was measured which had at the large end fifty four sap rings. The diameter was just two feet. The sap rings which were found nearest the heart were narrowest and smallest, from which they grew larger the further they lay from the heart out towards the surface.’ A cross-section cut from the trunk of a tree could not have been better described. The ‘sap rings’ are the record of the new wood lain down by each year’s growth beneath the bark: fifty-four rings is fifty-four years, the age of the tree. Our own wood needs just such a chronology.

The neighbouring wood has had some recent felling, and I can record the cleanly cut log-ends on display in a stack by the entrance to Grim’s Dyke Wood. Beech chronology turns out to be not quite as simple to measure as I might have thought. The good thing about our trees is that such straight trunks provide a reliable, nearly circular section. Nearer the ground the trunks are all buttressed and irregular, and no two diameters are the same; these undulations record the profiles of the ‘props’ that hold the trunks aloft. So the upper part of the tree – waist-height and above – provides the best experiment. Since all tree trunks do taper gently, different sections of the same tree will have decreasing diameter upwards. The difficulty is that the ‘narrowest and smallest’ rings in the centre of the tree are not so easy to read. Some years added no more than a millimetre of new wood.

I have to take a felled piece of heartwood home to see if I can tease out some figures. I laboriously buff it with fine sandpaper for hours, and as the distracting irregularities are polished away, so the early growth rings become clearer as darker lines. It is like seeing a diagnostic thumbprint slowly developing from obscurity. The wood almost shines pink-brown when I finally make out twenty-seven rings in thirty-five millimetres diameter. It evidently took a long time for this particular tree to get going, after which it sped up mightily. Even in the mature part of the tree not every ring announces itself clearly. There are good years and bad: the summers of 1974 and 1975 were droughts, and the growth rings would have been minimal. Skilled dendrochronologists can ‘read’ tree rings as a diary of climatic variation extending over centuries, but my skills do not extend that far. However, in older trees most of the rings add about three to four millimetres to the radius every year, and these can be counted easily enough. I eventually reach a consensus with my own scientific conscience. Several trees come out with eighty rings, more or less, possibly as many as eighty-five. Jackie provides a second pair of unbiased and independent eyes and tots up a similar figure. These are from trunks ranging in diameter from twenty-seven to fifty centimetres; and another trunk of forty-three-centimetre diameter has just under sixty rings. I cannot prove that the former come from higher in a tree that might have had a more impressive base. What I can say, with confidence, is that a number of beeches in Lambridge Wood grew from seedlings around 1930, and are now fine, big trees.

Читать дальше