1 ...7 8 9 11 12 13 ...19 In 1828 J.S. Mill undertook his own bipedal tour that passed through our part of Oxfordshire. 6Open fields yielded abundant white-flowered wild candytuft, ‘one of the commonest of all weeds’ ( Iberis amara ), which is now a rare plant – I eventually ran it down myself on clear ground on Swyncombe Down, nine miles from our wood. His record of thorow wax ( Bupleurum rotundifolium ) might be one of the last for the county: this species is close to extinction in Great Britain, and Mill noted its rarity even then. On 5 July he approached Henley from Nettlebed: our patch. You may imagine the pleasure his subsequent writing gave me.

The woods are the great beauty of this country. They are real woods, not copse, that is, they are not cut down for fire-wood, but allowed to grow into timber, though not to any great age, nor are there, as far as we could perceive, many very large or fine trees among them … We stopped at the White Hart, Nettlebed for the night, and in the evening walked down the hill by the Oxford Road towards Henley. It passes through a fine forest-like beech wood, and on the whole the ascent to Nettlebed from Henley is far more beautiful than any thing else which we have seen in its vicinity.

I cannot prove that John Stuart Mill walked exactly along the footpath past our wood, although it is hard to see how a woodland ascent towards Nettlebed from Henley could have taken any other route. His praise for its beauty is not the least of it. The woods he described are very like those that still flourish today in this corner of the Chiltern Hills; the same stately ‘forest’ of mature timber trees, but yet lacking any truly ancient giants such as survive in old parkland or as parish boundary markers. My wife and I discovered a massive ancient beech pollard along a path in Nettlebed that must have been four hundred years old at least, all gnarled and knobbly and hollowed out. There are a few in the area. But no, Lambridge Wood was a working wood two hundred years ago, a beechen grove permitted to grow on to timber, but not to senility. We shall see, however, that nothing is forever, and our wood would have had different employment in earlier and later times.

Nor can I prove that John Stuart Mill walked through the wood in the company of George Grote, but I like to think that circumstances favoured it. They were friends already in the early 1820s. Mill was both an admirer and a reviewer of Grote’s writing, and particularly his monumental history of Greece (1846–56) in twelve volumes: 7a work not perhaps as beloved as Gibbon on Rome, but with a similarly vast reach and ambition. The two prolific writers shared what might broadly be called liberal and reformist views, and were Utilitarians. The seat of the banking Grote family was Badgemore House, which has been mentioned as the estate adjoining Greys Court directly to the east. Part of the Henley end of Lambridge Wood was within that estate; tracks ran onwards into our part of the greater wood. George’s father was fond of country pursuits, and went hacking on horseback through our woods and onwards to Bix. Young George (then still a banker) and his wife would make the forty-mile journey from London to spend ten days with his parents, and on one occasion Mrs Grote drove all the way in her own one-horse vehicle while her husband rode for four hours separately on horseback. 8Although George Grote was much attached to Badgemore, in the days before the railway it was hardly a practical commute. By 1831 it was clear that the country house should be given up, and George left for the metropolis to devote more time to reformist politics. We shall see that all the manor houses surrounding our wood had political connections with the capital at one time or another.

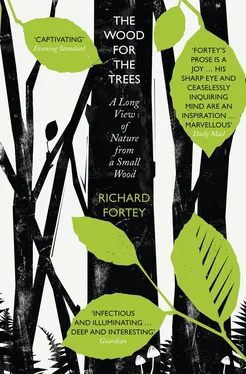

As for contemporary writers, Richard Mabey’s memoir of Chiltern countryside 9is centred on a region not very far from Lambridge Wood, while Ian McEwan described a long walk through our chalk country in his 2007 novel On Chesil Beach . This area of southern England proves to be almost as crawling with writers as with other invertebrates.

Hard grounds

The ground in this part of the wood is crunchy under my boots. Beneath a few of last year’s fallen leaves and under the questing loops of bramble shoots there appears to be nothing but rock. I am attempting to dig a hole to explore the surface geology, but my spade refuses to make any progress. Its blade twists and complains against a barrier of stones. I will have to employ my geological hammer to solve the problem.

The pick side of the hammer starts levering up lumpy flints, some bigger than my fist. They leave the damp ground reluctantly, with a sucking noise. Where I hammer downwards into the growing hole, sparks fly where steel meets flint. Briefly, there is a smell of cordite; in the days of flintlock pistols that smell would have been a familiar one. Flints were used to strike the spark that ignited gunpowder before a shot could be made. Our flints are embedded in reddish ochre clay that tries to hold on to them, clay that can easily be rolled into a coherent ball between the palms of my hands, and sticks to the fingers. The exterior of most of the flints is white when wiped clear of its clay coat, but where the hammer has shattered one of the larger flints its interior is strikingly black, and mottled in patches. It is a hard rock, but a brittle one shot through with flaws. Much of the wood is effectively floored with flint. Of the chalk of the Chilterns there is no sign.

Just down the hill beyond the Fair Mile I know that chalk underlies everything. When the dual-carriageway road was repaired great masses of the white rock were dumped on the side, and I picked out a typical, conical fossil sponge called Ventriculites from the rock pile. Even within Lambridge Wood, further downslope towards Henley, a mysterious excavation known as the Fairies’ Hole (marked on even the oldest maps) is undoubtedly dug within the white limestone. The rock that makes the whole range of hills, ‘the rock that bore them up all on its back’, as H.J. Massingham said, is an understory of chalk. Within the chalk, hard flints form discrete layers, but they never dominate completely. This flint was ultimately derived from fossil sponges within the chalk that had internal skeletons made of silica struts. The silica was first dissolved, and then re-deposited in flinty layers as the original chalk ooze gradually hardened and transformed into the rock we see today. Whatever underlies Grim’s Dyke Wood on the higher ground evidently also lies on top of the chalk formation, but is largely made of flints derived from it, all stuck in a matrix of sticky clay. This deposit is called, unsurprisingly, clay-with-flints, and in the wood the flints are dominant.

Clay-with-flints caps the chalk in many parts of the Chiltern Hills. 10It is the product of many millennia of slow solution and weathering-away of the chalk; it is what is left behind when everything else is removed. Chalk is weakly soluble in rainwater, which is why water derived from an aquifer in the Chilterns leaves a limescale deposit behind in a kettle. After a very long time, as the chalk naturally disappears the originally scattered flints become concentrated. Flint is insoluble; in fact, this form of silica is well-nigh indestructible. It can be tossed into rivers or buried in gardens for centuries, and emerges unscathed. It will outlast the Chilterns.

To estimate the thickness of the clay-with-flint capping I walk slowly up from the end of the Fair Mile to Lambridge Wood along Pickpurse Lane (see comments on highwaymen), digging with my hammer into the bank until the telltale milkiness goes out of the soil. There are other signs to look for. Old man’s beard ( Clematis vitalba ), the nearest thing in the British flora to a liana, only grows on chalk – it will not tolerate clay-with-flints. Wild marjoram is no more forgiving. Plant roots sense chemistry with the exquisite palate of a connoisseur. Both the indicator plants grow in abundance near the bottom of the lane and fade away upward. By the time all evidence of chalk has disappeared I conclude that very roughly twenty feet of clay-with-flints must lie above. That is sufficient to make the thin soil on the high ground neutral or acidic compared with the alkaline soils on the slope and in the valley bottom. This saddens me, for many of the more glamorous plants love chalk: the whitebeam tree with big simple leaves with shining undersides; cheerful yellow St John’s wort; and many an orchid. I shall just have to live without them – I cannot argue with geology. Now I also know why our footpaths can become like quagmires after too much rain. That layer of impermeable clay does not drain well; it likes to make ponds. Some corner of our wood will always be damp.

Читать дальше