Under Heaven

Guy Gavriel Kay

HarperCollins Publishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Published by HarperCollins Publishers 2010

Copyright © Guy Gavriel Kay 2010

Guy Gavriel Kay asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollins Publishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 978007242913

EBook Edition © 2006 ISBN: 9780007342020

Version: 2018-08-07

to Sybil, with love

With bronze as a mirror one can correct one’s appearance; with history as a mirror, one can understand the rise and fall of a state; with good men as a mirror, one can distinguish right from wrong.

—LI SHIMIN, TANG EMPEROR TAIZONG

…peace to our children when they fall in small war on the heels of small war—until the end of time…

—ROBERT LOWELL

Cover Page

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Maps

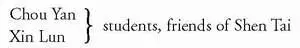

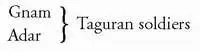

PRINCIPAL CHARACTERS

PART ONE

CHAPTER I

CHAPTER II

CHAPTER III

CHAPTER IV

CHAPTER V

CHAPTER VI

CHAPTER VII

CHAPTER VIII

PART TWO

CHAPTER IX

CHAPTER X

CHAPTER XI

CHAPTER XII

CHAPTER XIII

CHAPTER XIV

PART THREE

CHAPTER XV

CHAPTER XVI

CHAPTER XVII

CHAPTER XVIII

CHAPTER XIX

CHAPTER XX

CHAPTER XXI

CHAPTER XXII

PART FOUR

CHAPTER XXIII

CHAPTER XXIV

CHAPTER XXV

CHAPTER XXVI

CHAPTER XXVII

KEEP READING

EPILOGUE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ALSO BY GUY GAVRIEL KAY

About the Publisher

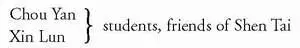

The Imperial Family, and Ta-Ming Palace mandarins

Taizu, the Son of Heaven, emperor of Kitai

Shinzu, his third son, and heir

Xue, his thirty-first daughter

Wen Jian, the Precious Consort, also called the Beloved Companion

Chin Hai, formerly first minister, now deceased

Wen Zhou, first minister of Kitai, cousin to Wen Jian

The Shen Family

General Shen Gao, deceased, once Left Side Commander of the Pacified West

Shen Liu, his oldest son, principal adviser to the first minister

Shen Tai, his second son

Shen Chao, his third son

Shen Li-Mei, his daughter

The Army

An Li (“Roshan”), military governor of the Seventh, Eighth, and Ninth Districts

An Rong, his oldest son

An Tsao, a younger son

Xu Bihai, military governor of the Second and Third Districts, in Chenyao

Xu Liang, his older daughter

Lin Fong, commander of Iron Gate Fortress

Wujen Ning, a soldier at Iron Gate

Tazek Karad, an officer on the Long Wall

Kanlin Warriors

Wan-si

Wei Song

Lu Chen

Ssu Tan

Zhong Ma

Artists

Sima Zian, a poet, the Banished Immortal

Chan Du, a poet

In Xinan, the capital

Spring Rain, a courtesan in the North District, later named Lin Chang

Feng, a guard in the employ of Wen Zhou

Hwan, a servant of Wen Zhou

Pei Qin, a beggar in the street

Ye Lao, a steward

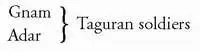

Beyond the borders of Kitai

West

Sangrama the Lion, ruling the Empire of Tagur

Cheng-wan, the White Jade Princess, one of his wives, seventeenth daughter of Emperor Taizu

Bytsan sri Nespo, a Taguran army officer

Nespo sri Mgar, his father, a senior officer

North

Dulan, kaghan of the Bogü people of the steppe

Hurok, his sister’s husband, later kaghan

Meshag, Hurok’s older son

Tarduk, Hurok’s second son

PART ONE

Amid the ten thousand noises and the jade-and-gold and the whirling dust of Xinan, he had often stayed awake all night among friends, drinking spiced wine in the North District with the courtesans.

They would listen to flute or pipa music and declaim poetry, test each other with jibes and quotes, sometimes find a private room with a scented, silken woman, before weaving unsteadily home after the dawn drums sounded curfew’s end, to sleep away the day instead of studying.

Here in the mountains, alone in hard, clear air by the waters of Kuala Nor, far to the west of the imperial city, beyond the borders of the empire, even, Tai was in a narrow bed by darkfall, under the first brilliant stars, and awake at sunrise.

In spring and summer the birds woke him. This was a place where thousands upon thousands nested noisily: fishhawks and cormorants, wild geese and cranes. The geese made him think of friends far away. Wild geese were a symbol of absence: in poetry, in life. Cranes were fidelity, another matter.

In winter the cold was savage, it could take the breath away. The north wind when it blew was an assault, outdoors, and even through the cabin walls. He slept under layers of fur and sheepskin, and no birds woke him at dawn from the icebound nesting grounds on the far side of the lake.

The ghosts were outside in all seasons, moonlit nights and dark, as soon as the sun went down.

Tai knew some of their voices now, the angry ones and the lost ones, and those in whose thin, stretched crying there was only pain.

They didn’t frighten him, not any more. He’d thought he might die of terror in the beginning, alone in those first nights here with the dead.

He would look out through an unshuttered window on a spring or summer or autumn night, but he never went outside. Under moon or stars the world by the lake belonged to the ghosts, or so he had come to understand.

He had set himself a routine from the start, to deal with solitude and fear, and the enormity of where he was. Some holy men and hermits in their mountains and forests might deliberately act otherwise, going through days like leaves blown, defined by the absence of will or desire, but his was a different nature, and he wasn’t holy.

He did begin each morning with the prayers for his father. He was still in the formal mourning period and his self-imposed task by this distant lake had everything to do with respect for his father’s memory.

Читать дальше