PART TWO

I

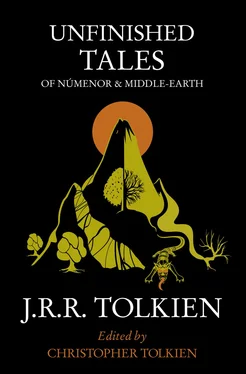

A Description of the Island of Númenor

Although descriptive rather than narrative, I have included selections from my father’s account of Númenor, more especially as it concerns the physical nature of the Island, since it clarifies and naturally accompanies the tale of Aldarion and Erendis. This account was certainly in existence by 1965, and was probably written not long before that.

I have redrawn the map from a little rapid sketch, the only one, as it appears, that my father ever made of Númenor. Only names or features found on the original have been entered on the redrawing. In addition, the original shows another haven on the Bay of Andúnië, not far to the westward of Andúnië itself; the name is hard to read, but is almost certainly Almaida . This does not, so far as I am aware, occur elsewhere.

II

Aldarion and Erendis

This story was left in the least developed state of all the pieces in this collection, and has in places required a degree of editorial rehandling that made me doubt the propriety of including it. However, its very great interest as the single story (as opposed to records and annals) that survived at all from the long ages of Númenor before the narrative of its end (the Akallabêth ), and as a story unique in its content among my father’s writings, persuaded me that it would be wrong to omit it from this collection of ‘Unfinished Tales’.

To appreciate the necessity for such editorial treatment it must be explained that my father made much use, in the composition of narrative, of ‘plot-outlines’, paying meticulous attention to the dating of events, so that these outlines have something of the appearance of annal-entries in a chronicle. In the present case there are no less than five of these schemes, varying constantly in their relative fullness at different points and not infrequently disagreeing with each other at large and in detail. But these schemes always had a tendency to move into pure narrative, especially by the introduction of short passages of direct speech; and in the fifth and latest of the outlines for the story of Aldarion and Erendis the narrative element is so pronounced that the text runs to some sixty manuscript pages.

This movement away from a staccato annalistic style in the present tense into fullblown narrative was however very gradual, as the writing of the outline progressed; and in the earlier part of the story I have rewritten much of the material in the attempt to give some degree of stylistic homogeneity throughout its course. This rewriting is entirely a matter of wording, and never alters meaning or introduces unauthentic elements.

The latest ‘scheme’, the text primarily followed, is entitled The Shadow of the Shadow: the Tale of the Mariner’s Wife; and the Tale of the Queen Shepherdess . The manuscript ends abruptly, and I can offer no certain explanation of why my father abandoned it. A typescript made to this point was completed in January 1965. There exists also a typescript of two pages that I judge to be the latest of all these materials; it is evidently the beginning of what was to be a finished version of the whole story, and provides the text on pp. 223– 5in this book (where the plot-outlines are at their most scanty). It is entitled Indis i·Kiryamo ‘The Mariner’s Wife’: a tale of ancient Númenórë, which tells of the first rumour of the Shadow .

At the end of this narrative (p. 264) I have set out such scanty indications as can be given of the further course of the story.

III

The Line of Elros: Kings of Númenor

Though in form purely a dynastic record, I have included this because it is an important document for the history of the Second Age, and a great part of the extant material concerning that Age finds a place in the texts and commentary in this book. It is a fine manuscript in which the dates of the Kings and Queens of Númenor and of their reigns have been copiously and sometimes obscurely emended: I have endeavoured to give the latest formulation. The text introduces several minor chronological puzzles, but also allows clarification of some apparent errors in the Appendices to The Lord of the Rings .

The genealogical table of the earlier generations of the Line of Elros is taken from several closely-related tables that derive from the same period as the discussion of the laws of succession in Númenor (pp. 268– 9). There are some slight variations in minor names: thus Vardilmë appears also as Vardilyë , and Yávien as Yávië . The forms given in my table I believe to be later.

IV

The History of Galadriel and Celeborn

This section of the book differs from the others (save those in Part Four) in that there is here no single text but rather an essay incorporating citations. This treatment was enforced by the nature of the materials; as is made clear in the course of the essay, a history of Galadriel can only be a history of my father’s changing conceptions, and the ‘unfinished’ nature of the tale is not in this case that of a particular piece of writing. I have restricted myself to the presentation of his unpublished writings on the subject, and forgone any discussion of the larger questions that underlie the development; for that would entail consideration of the entire relation between the Valar and the Elves, from the initial decision (described in The Silmarillion ) to summon the Eldar to Valinor, and many other matters besides, concerning which my father wrote much that falls outside the scope of this book.

The history of Galadriel and Celeborn is so interwoven with other legends and histories – of Lothlórien and the Silvan Elves, of Amroth and Nimrodel, of Celebrimbor and the making of the Rings of Power, of the war against Sauron and the Númenórean intervention – that it cannot be treated in isolation, and thus this section of the book, together with its five Appendices, brings together virtually all the unpublished materials for the history of the Second Age in Middle-earth (and the discussion in places inevitably extends into the Third). It is said in the Tale of Years given in Appendix B to The Lord of the Rings : ‘These were the dark years for Men of Middle-earth, but the years of the glory of Númenor. Of events in Middle-earth the records are few and brief, and their dates are often uncertain.’ But even that little surviving from the ‘dark years’ changed as my father’s contemplation of it grew and changed; and I have made no attempt to smooth away inconsistency, but rather exhibited it and drawn attention to it.

Divergent versions need not indeed always be treated solely as a question of settling the priority of composition; and my father as ‘author’ or ‘inventor’ cannot always in these matters be distinguished from the ‘recorder’ of ancient traditions handed down in diverse forms among different peoples through long ages (when Frodo met Galadriel in Lórien, more than sixty centuries had passed since she went east over the Blue Mountains from the ruin of Beleriand). ‘Of this two things are said, though which is true only those Wise could say who now are gone.’

In his last years my father wrote much concerning the etymology of names in Middle-earth. In these highly discursive essays there is a good deal of history and legend embedded; but being ancillary to the main philological purpose, and introduced as it were in passing, it has required extraction. It is for this reason that this part of the book is largely made up of short citations, with further material of the same kind placed in the Appendices.

PART THREE

I

The Disaster of the Gladden Fields

This is a ‘late’ narrative – by which I mean no more, in the absence of any indication of precise date, than that it belongs in the final period of my father’s writing on Middle-earth, together with ‘Cirion and Eorl’, ‘The Battles of the Fords of Isen’, ‘the Drúedain’, and the philological essays excerpted in ‘The History of Galadriel and Celeborn’, rather than to the time of the publication of The Lord of the Rings and the years following it. There are two versions: a rough typescript of the whole (clearly the first stage of composition), and a good typescript incorporating many changes that breaks off at the point where Elendur urged Isildur to flee (p. 355). The editorial hand has here had little to do.

Читать дальше