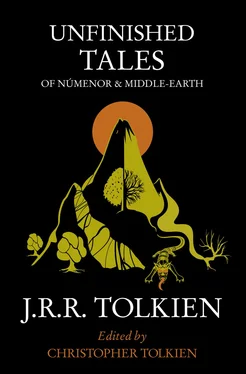

Many of the pieces in this collection are elaborations of matters told more briefly, or at least referred to, elsewhere; and it must be said at once that much in the book will be found unrewarding by readers of The Lord of the Rings who, holding that the historical structure of Middle-earth is a means and not an end, the mode of the narrative and not its purpose, feel small desire of further exploration for its own sake, do not wish to know how the Riders of the Mark of Rohan were organised, and would leave the Wild Men of the Drúadan Forest firmly where they found them. My father would certainly not have thought them wrong. He said in a letter written in March 1955, before the publication of the third volume of The Lord of the Rings :

I now wish that no appendices had been promised! For I think their appearance in truncated and compressed form will satisfy nobody: certainly not me; clearly from the (appalling mass of ) letters I receive not those people who like that kind of thing – astonishingly many; while those who enjoy the book as an ‘heroic romance’ only, and find ‘unexplained vistas’ part of the literary effect, will neglect the appendices, very properly.

I am not now at all sure that the tendency to treat the whole thing as a kind of vast game is really good – certainly not for me, who find that kind of thing only too fatally attractive. It is, I suppose, a tribute to the curious effect that story has, when based on very elaborate and detailed workings of geography, chronology, and language, that so many should clamour for sheer ‘information’, or ‘lore’.

In a letter of the following year he wrote:

... while many like you demand maps, others wish for geological indications rather than places; many want Elvish grammars, phonologies, and specimens; some want metrics and prosodies.... Musicians want tunes, and musical notation; archaeologists want ceramics and metallurgy; botanists want a more accurate description of the mallorn , of elanor , niphredil , alfirin , mallos , and symbelmynë ; historians want more details about the social and political structure of Gondor; general enquirers want information about the Wainriders, the Harad, Dwarvish origins, the Dead Men, the Beornings, and the missing two wizards (out of five).

But whatever view may be taken of this question, for some, as for myself, there is a value greater than the mere uncovering of curious detail in learning that Vëantur the Númenórean brought his ship Entulessë, the ‘Return’, into the Grey Havens on the spring winds of the six hundredth year of the Second Age, that the tomb of Elendil the Tall was set by Isildur his son on the summit of the beacon-hill Halifirien, that the Black Rider whom the Hobbits saw in the foggy darkness on the far side of Bucklebury Ferry was Khamûl, chief of the Ringwraiths of Dol Guldur – or even that the childlessness of Tarannon twelfth King of Gondor (a fact recorded in an Appendix to The Lord of the Rings ) was associated with the hitherto wholly mysterious cats of Queen Berúthiel.

The construction of the book has been difficult, and in the result is somewhat complex. The narratives are all ‘unfinished’, but to a greater or lesser degree, and in different senses of the word, and have required different treatment; I shall say something below about each one in turn, and here only call attention to some general features.

The most important is the question of ‘consistency’, best illustrated from the section entitled ‘The History of Galadriel and Celeborn’. This is an ‘Unfinished Tale’ in a larger sense: not a narrative that comes to an abrupt halt, as in ‘Of Tuor and his Coming to Gondolin’, nor a series of fragments, as in ‘Cirion and Eorl’, but a primary strand in the history of Middle-earth that never received a settled definition, let alone a final written form. The inclusion of the unpublished narratives and sketches of narrative on this subject therefore entails at once the acceptance of the history not as a fixed, independently-existing reality which the author ‘reports’ (in his ‘persona’ as translator and redactor), but as a growing and shifting conception in his mind. When the author has ceased to publish his works himself, after subjecting them to his own detailed criticism and comparison, the further knowledge of Middle-earth to be found in his unpublished writings will often conflict with what is already ‘known’; and new elements set into the existing edifice will in such cases tend to contribute less to the history of the invented world itself than to the history of its invention. In this book I have accepted from the outset that this must be so; and except in minor details such as shifts in nomenclature (where retention of the manuscript form would lead to disproportionate confusion or disproportionate space in elucidation) I have made no alterations for the sake of consistency with published works, but rather drawn attention throughout to conflicts and variations. In this respect therefore ‘Unfinished Tales’ is essentially different from The Silmarillion , where a primary though not exclusive objective in the editing was to achieve cohesion both internal and external; and except in a few specified cases I have indeed treated the published form of The Silmarillion as a fixed point of reference of the same order as the writings published by my father himself, without taking into account the innumerable ‘unauthorised’ decisions between variants and rival versions that went into its making.

In content the book is entirely narrative (or descriptive): I have excluded all writings about Middle-earth and Aman that are of a primarily philosophic or speculative nature, and where such matters from time to time arise I have not pursued them. I have imposed a simple structure of convenience by dividing the texts into Parts corresponding to the first Three Ages of the World, there being in this inevitably some overlap, as with the legend of Amroth and its discussion in ‘The History of Galadriel and Celeborn’. The fourth part is an appendage, and may require some excuse in a book called ‘Unfinished Tales’, since the pieces it contains are generalised and discursive essays with little or no element of ‘story’. The section on the Drúedain did indeed owe its original inclusion to the story of ‘The Faithful Stone’ which forms a small part of it; and this section led me to introduce those on the Istari and the Palantíri, since they (especially the former) are matters about which many people have expressed curiosity, and this book seemed a convenient place to expound what there is to tell.

The notes may seem to be in some places rather thick on the ground, but it will be seen that where clustered most densely (as in ‘The Disaster of the Gladden Fields’) they are due less to the editor than to the author, who in his later work tended to compose in this way, driving several subjects abreast by means of interlaced notes. I have throughout tried to make it clear what is editorial and what is not. And because of this abundance of original material appearing in the notes and appendices I have thought it best not to restrict the page-references in the Index to the texts themselves but to cover all parts of the book except the Introduction.

I have throughout assumed on the reader’s part a fair knowledge of the published works of my father (more especially The Lord of the Rings ), for to have done otherwise would have greatly enlarged the editorial element, which may well be thought quite sufficient already. I have, however, included short defining statements with almost all the primary entries in the Index, in the hope of saving the reader from constant reference elsewhere. If I have been inadequate in explanation or unintentionally obscure, Mr Robert Foster’s Complete Guide to Middle-earth supplies, as I have found through frequent use, an admirable work of reference.

Читать дальше