And some good cases were made, the best by my dad’s sister in Kansas City, my Aunt Noreen, who was married to a lawyer, lived in a five-bedroom house with a swimming pool, had only one child, a girl, Phoebe, and was desperate for a son, but unable to bear any more children. No one considered for a moment that Dad might want to raise his own sons.

But my dad, big awkward rough diamond that he was, refused all their offers, even ignored Aunt Noreen, who, after being turned down, threatened to sue for custody on the grounds that Dad lacked the ability to care for us properly. It was about ten years before Dad forgave his sister for that threat. He intended to look after us himself, he said. And when Dad says something, he means it.

It wasn’t easy. There were housekeepers, play schools, and day-care centers. There were babysitters who did exactly that – sat – often having friends over who ate everything not locked up. There were housekeepers who drank, who entertained boyfriends, who quit on a moment’s notice, stealing whatever they were able to carry.

There were also some wonderful women who tried to be mothers to Byron and me, some hoping Dad would take a fancy to them if they were nice enough to us and kept the house spotless. Others simply loved children. One was a middle-aged lady named Mrs. Watts, a black woman whose family had a cottage on a lake some fifty miles out of Chicago. She took us to the lake for two weeks when I was eight and Byron was six. Dad came down on the weekends and slept in a hammock on the porch of the cabin, and we went fishing and boating and collected rocks and shells. But Mrs. Watts’ mother became ill and she had to go look after her instead of us.

It was Dad who enrolled me in Little League, where I immediately showed skill and power beyond my years.

‘Did you ever play ball?’ I asked him.

‘I used to play in a commercial league when I was a teenager. I played third base with all the grace of King Kong. The thing I did best was get hit by the pitcher. The ball didn’t hurt so much because I have big bones. I’d lean over the plate and dare the pitcher to hit me, and often enough he would.’

We muddled through. By the time 1 was in first grade I’d mastered the washer and dryer, the vacuum cleaner and the dishwasher. We went to school in clean if unironed clothes. I did the dishes as soon as I got home from school. Byron learned to cook, first out of necessity then for pleasure. I can see him standing on a chair in front of the stove, five years old, frying pork chops, boiling carrots that I had cut up, salting, peppering, shooing me away if I tried to help. We got our share of burns and scrapes and cuts, but we were truly scared only once. When I was six, I reached up and put my finger under the knife as Dad was slicing bread for Sunday morning toast. I still have the scar. There was blood everywhere, and Byron kept a washcloth pressed tightly about my finger as Dad hurried us to Emergency, the cloth turning raspberry colored in spite of the pressure Byron put on it.

‘How long will he be on the disabled list?’ Dad asked the doctor after he had stitched me up. ‘This boy’s the star of his Little League team and he’s only six.’ I was pale and still snuffling a little. My knees were like water, and I didn’t feel the least like a star baseball player.

The hand recovered, and I roared through every league I played in. Our high-school team won twenty-seven games in a row my freshman year and, though we lost in the first round of the Illinois State Championships, I was voted outstanding player.

Afterward, my coach told me a scout from the White Sox had been in the stands for a couple of games.

‘Didn’t want to put any pressure on you, Son, so I didn’t tell you. You’ve got a big-league future in front of you, or I don’t know my baseball players. You’ve got all the tools. Speed, a strong arm, and a good eye will make up for your lack of power. You’re gonna be a great one.’

Had he not told me about the scout because he knew I didn’t play well under pressure? Or hadn’t he noticed? I’d gone 0–5 in our tournament loss, and made an error.

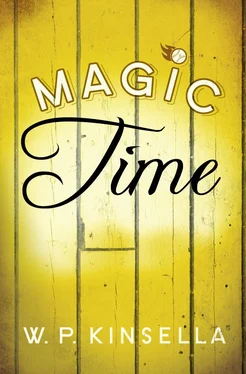

TWO Contents Title Page Magic Time BY W. P. KINSELLA Copyright The Friday Project An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd 77–85 Fulham Palace Road Hammersmith, London W6 8JB www.harpercollins.co.uk This ebook first published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Publishers Ltd 2014 Copyright © W. P. Kinsella 2001 Cover design © HarperCollins Publishers Ltd 2014 W. P. Kinsella asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work. FIRST EDITION A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library. This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins. Source ISBN: 9780007497577 Ebook Edition © July 2014 ISBN: 9780007497584 Version 2014-07-31 Prologue 1: Judging Distances ONE TWO THREE FOUR FIVE 2: One Road Runs Straight SIX SEVEN EIGHT NINE TEN 3: Fred Noonan’s Town ELEVEN TWELVE THIRTEEN FOURTEEN FIFTEEN SIXTEEN 4: Barry McMartin SEVENTEEN EIGHTEEN 5: Safe at Home NINETEEN TWENTY TWENTY-ONE TWENTY-TWO TWENTY-THREE 6: Magic Time TWENTY-FOUR TWENTY-FIVE TWENTY-SIX TWENTY-SEVEN Also by the W.P. Kinsella About the Publisher

I was in my second year of high school the day a Cadillac the color of thick, rich cream pulled up in front of Mrs. Grover’s Springtime Café and Ice Cream Parlor. Our main street was paved but narrow, with six feet of gravel between the edge of the pavement and the sidewalk. Dust from the gravel whooshed past the car and oozed through the screen door of the café.

Byron and I were seated at a glass-topped table, our feet hooked on the insect-legged chairs. We were sharing a dish of vanilla ice cream, savoring each bite, trying to make it outlast the heat of high July.

It was easy to tell the Cadillac owner was a man who cared about his car. He checked his rear view carefully before opening the driver’s door. After he got out – ‘unwound’ would be a better description, for he was six foot five if he was an inch – he closed the door gently but firmly, then wiped something off the side-view mirror with his thumb. On the way around the Caddy, he picked something off the grille and flicked it onto the road.

He took a seat in a corner of the café where he could watch his car and everyone else in the café which was me, Byron, and Mrs. Grover.

The stranger looked to be in his mid-thirties. He had rusty hair combed into a high pompadour that accentuated his tall front teeth and made his face look longer than it really was. Across his upper lip was a wide coppery-red mustache with the corners turned up and waxed, the kind worn by 1890s baseball players.

Though everything about him was expensive, down to the diamond ring on his left baby finger, he looked like the type who didn’t like to conform. I guessed he had grown his hair down past his shoulders when he was a teenager. His hair was now combed back, hiding the top half of his ears and the back of his collar. He was wearing a black suit with fine gray pinstripes, a white-on-white shirt, and shoes that must have cost three hundred dollars.

Читать дальше