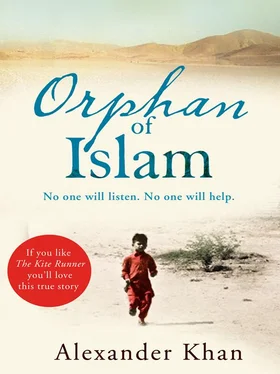

No one will listen. No one will help.

I dedicate this book to Abad.

Without his help I would not be here.

And to my wife Jessica –

I love you very much.

Title Page

Dedication

Map

Author’s Note

Prologue

The mullah bends down, his long grey-black beard brushing agains…

Chapter One

I see a face, a white face, but I don’t…

Chapter Two

We were met at Heathrow by a gaggle of relatives…

Chapter Three

After ten months at Fatima’s I’d become used to Dad…

Chapter Four

We arrived at Hamilton Terrace to find the house deserted.

Chapter Five

In Dad’s absence Rafiq appeared to make himself useful, at…

Chapter Six

I was about 15 feet up, but it felt like…

Chapter Seven

All that flight I kept checking to see if I…

Chapter Eight

The next few days were spent exploring my immediate surroundings.

Chapter Nine

The group that gathered for our farewell to Pakistan wasn’t…

Chapter Ten

After prayers we trooped back to the sleeping quarters. The…

Chapter Eleven

I lay awake most of that night, pain and worry…

Chapter Twelve

I pestered Abad several times to tell me what he…

Chapter Thirteen

The village of small mud houses that lay at the…

Chapter Fourteen

The journey was long, two or three hours, and I…

Chapter Fifteen

I woke to the sound of the early morning call…

Chapter Sixteen

Malik wasn’t the only rebel kid in the village. There…

Chapter Seventeen

One afternoon, 10 days or so before Fatima and Ayesha’s…

Chapter Eighteen

There was a minibus waiting at Heathrow to take me…

Epilogue

I’m standing on the doorstep of a council house near…

Acknowledgments

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

I hope my story is inspirational for those who might find themselves in similar situations and think there is no hope and no way out. There is always a way out, even when the odds are stacked against you and the wall seems very high.

I’ve been there, scared, not knowing who to ask for help. It’s not a nice feeling.

www.alexander-khan.co.uk is a website that offers confidential help and advice to people in similar situations to those described in this book.

1988. HAQQANIA MADRASSA, NORTH-WEST PAKISTAN

The mullah bends down, his long grey-black beard brushing against my feet as he unlocks the leg brace. I’ve been standing rigid in it for at least three hours, unable to sit, kneel or even squat for fear of snapping my ankles. I could cry with relief, but I’m too frightened to cry. At least not yet.

He points to the blackboard in front of me with his bamboo stick, the one he uses to whack us all with when we can’t pronounce something from the Holy Book. My Arabic is rubbish; I’m very used to that stick.

‘Read it,’ he commands, glaring at me with dark eyes.

All the lights have gone out across the madrassa and the only illumination in the room is a lantern with a tiny wick. I read the chalked scripture slowly, trying to pronounce all the words right:

‘La ilaha illallah Muhammad rasul Allah’ (‘There is no God but Allah, and Muhammad is His Messenger.’)

Whack! The stick comes across my shoulders. Wrong again. Hearing Arabic spoken is one thing, trying to read it quite another, and my northern English accent easily wins out. The mullah glares at me with undisguised contempt.

‘Go back to your room,’ he says. ‘We’ll see each other in here again tomorrow. You’re a disgrace to Islam.’

I stumble through the darkness to the dormitory and feel my way across the room to my blanket. Most of the boys are sleeping. I lie down and start to cry, as quietly as I can. The question goes through my mind, the same question that nags me night and day: how the hell have I ended up here? An ordinary lad from Lancashire stuck in some kind of weird medieval fairy story, but with no sign of a happy ending …

Back home, my mates are secretly listening to Bros or Guns n’ Roses in their bedrooms, hoping their dads won’t catch them and send them for an extra session of prayer at the mosque. That is as bad as life gets for them; why have I been singled out for such harsh punishment so far from home? What have I done to deserve this?

I see a face, a white face, but I don’t recall any features other than dark eyes and a smile. What I remember most is her long dark hair. As she bends down, it tickles the sides of my cheeks and I laugh. She laughs too, then the sun comes out and streams through the thin curtains of the living room. She turns away and is gone. This is the only memory of my mum I have from childhood.

I’ve no idea what she was like as a mother during those brief first few years. I can’t recall the stories she told, the food she cooked, the games she played or even the sound of her voice. There is no scent in this world that evokes her smell, no object or place that brings back those precious moments in time. Dark hair and a white face are all I have, and while that hasn’t been much, it has been enough to hang on to in my worst moments. I always knew she was out there somewhere, even when she’d apparently vanished from the face of the Earth. All I wanted was her to come back and take us home.

What I know about Margaret Firth is what I’ve pieced together over the years and what I’ve learned more recently. She was born near Manchester, the youngest of three sisters living in a house of poverty and pain. Her parents had little time or regard for her. Although she looked up to her sisters, it wasn’t the easiest of relationships. When her elder siblings moved out and made lives for themselves she would go to live with them from time to time, returning to her parents’ home when they’d had enough of her. It was a lonely life, back and forth between people who didn’t really want her. Her parents worked in the textile industry. Margaret would eventually do the same, getting a job in a local mill as soon as she left school.

My father, Ahmed Khan, was born in the village of Tajak, in the Attock district of north-west Pakistan. It is a rural and deeply religious area not far from the North-West Frontier and the border with Afghanistan. Ahmed was the eldest of five siblings: three brothers and two sisters. For the first 30 or so years of his life he lived pretty much how people have lived in this area, close to the Indus river, for many years. The men rise before dawn and go to the mosque for prayers. They return home to walled compounds containing several houses occupied by members of the extended family. Their wives are already up and have prayed in their living rooms on a mat facing Mecca. Then it is into the kitchen to cook curry and chapatis. The food is placed in a small clay pot with a lid on and given to the men as they head out for a day working in the harat, or field. Each family has its own plot of land, irrigated by a large well and including a small brick hut containing tools. Many men spend their entire lives in this routine, their faces etched with deep lines by the sun. Others become drivers or co-drivers of the trucks and buses that travel ceaselessly across Pakistan and beyond. Some turn into mechanics and set up their own garages; others open grocers’ shops. In these rural villages the women just stay at home, raise children and keep house. They are not allowed to do much else.

Читать дальше