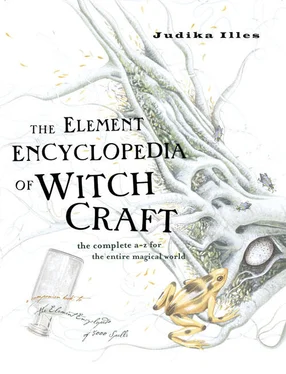

We’re going in circles. With all these contradictions and ambiguity one would imagine the witch to be some obscure figure. This couldn’t be further from the truth. It would be extremely difficult to find anyone, from the smallest child to the most remote villager, who doesn’t know what a witch is—or at least a witch as defined by their definition.

This passionate debate regarding the true identity of witches only underscores how deeply the witch resonates in each person’s consciousness. Because one’s own individual personal definition rings so clearly and profoundly, any other definition seems inadequate, misguided or just plain wrong. Witches evoke a passionate response, whether that passion resonates as fear or as love. People emulate witches. They long for witches in times of trouble. They run from witches as sources of trouble. Witches are held up as role models or as examples of exactly what not to be. Even those who fear, hate, and despise witches can’t leave them alone, as history has too often tragically proved.

If one attempts to remove the witch-figure from worldwide folklore, you promptly eliminate the vast majority of fairy and folk tales. Think about the Western canon of fairy tales: if there’s no witch, then there’s no Hansel and Gretel , no Beauty and the Beast, no Snow White or Rapunzel . Witchcraft doesn’t only figure in entertainment dating from days of yore; the witch continually reappears, evolving with the times. Need we even say “ Harry Potter ”? If there’s no witch, count the movies, books, and television shows that no longer exist. Now some might protest that these works do not reflect the reality of witchcraft, but as we’ve seen, there is no single, simple reality of witchcraft. Witchcraft is important precisely because it’s so fluid, so mysterious, so resistant to definition, so able to touch so many different buttons in so many souls.

Is there any common denominator that underlies or unifies all these differing theories of witchcraft? Maybe. There is yet another theory of witchcraft. This vision understands witchcraft to be the surviving vestiges of ancient Paleolithic culture originally shared by all human societies all over Earth: witchcraft as the original religion, the cult of Earth’s powers, the mother of spirituality. As people spread out, migrated and diverged, variations emerged; however witchcraft’s roots remain universal. As Funk and Wagnalls succinctly put it: “ Belief in witches exists in all lands, from earliest times to the present day .” This primal witch is our shared human heritage, although whether one reacts to her with love, awe, fear, and/or revulsion depends upon many factors.

Modern religions/spiritual paths as well as magical practices of all kinds, including the healing arts, may be understood as descending from this primal “witchcraft”’—or as reactions against it. Those who understand witches to be not flesh-and-blood reality but stories and archetypes can also trace the descent of their witch from this primal witchcraft.

Another way of understanding this primal witchcraft is as a worldview, a way of seeing, looking at and understanding the universe. Looking at the witch reveals more about the gazer then the witch. Instead, let’s try looking through that primal witch’s eyes. In witchcraft’s worldview, Earth is a place of mystery and wonder, full of powers of which one can avail oneself, if one only knows how. The witch is the one who knows . A good majority of the words used around the world, in various languages, not just Anglo-Saxon, to identify the concept of the “ witch ” involve acquisition of wisdom. A Russian euphemism for witches and sorcerers translates as “ people with knowledge .” The witch isn’t just a smart person, however; what the witch knows is more than just common knowledge. The witch knows Earth’s secrets.

Whether you perceive the witch as powerful or evil may depend upon whether you perceive knowledge as desirable or dangerous; whether you perceive that human knowledge is something that should be limited. The witch doesn’t think so. She, or he as the case may be, wants to know . This may be the heart of the matter.

Saint Patrick’s Breastplate, a famous Irish prayer attributed to that snake-banishing saint, begs God’s protection against “incantations of false prophets, against the black laws of paganism, against spells of women, smiths and druids, against all knowledge that is forbidden the human soul.”

Although in Christian myth, Original Sin, triggered by the serpent’s temptation of Eve, is often understood to be sex, a close reading of the Bible reveals that what the snake really offers Eve is knowledge . In fact, wherever snakes and people exist together, snakes are associated with wisdom—and with witchcraft. In various subversive retellings of that biblical tale, ancient Gnostic as well as neo-Pagan, the snake is attempting to assist Eve, to be her ally, not to entrap her.

Looking through the witch’s eyes may offer a very different perspective than that which many modern people are accustomed. One sees a world of power and mystery, full of secrets, delights, and dangers to be uncovered. However it is not a black-and-white world; it is not a world with rigidly distinct boundaries but a transformative world, a world filled with possibility , not what is but what could be , a blending, fluid, shifting but rhythmically consistent landscape.

It is no accident that the heavenly body universally associated with witchcraft is the moon, whose shape changes continually, although her rhythm is constant

It is no accident that the element universally associated with witchcraft is water, whose tides are ruled by the moon; water appears, disappears, changes shape, shifts continually, but remains rhythmically constant

It is no accident that the element universally associated with witchcraft is water, whose tides are ruled by the moon; water appears, disappears, changes shape, shifts continually, but remains rhythmically constant

It is no accident that the human gender most associated with witchcraft is the female one: the female body, like lunar phases and ocean tides, changes continually, often to the despair of the individual woman herself, although the rhythms also possess consistency if we let ourselves feel them.

It is no accident that the human gender most associated with witchcraft is the female one: the female body, like lunar phases and ocean tides, changes continually, often to the despair of the individual woman herself, although the rhythms also possess consistency if we let ourselves feel them.

Although this may resonate in the souls of witches it doesn’t explain the allure witches hold for so many who do not identify themselves as witches. Why the almost universal fascination with witches? Maybe because they’re fun. Yes, there are tragedies associated with witchcraft (just look at this book’s section on the Burning Times), sorry days in the history of witchcraft, but those tragedies are not witchcraft’s defining factor. So many in both the general public and the magical community are attracted to witches precisely because they are fun, and in fact that’s a very serious point about witchcraft.

During a particularly dour era in Europe, between the fourteenth and eighteenth centuries, witches were consistently condemned for, among other things, having fun. Among the charges typically brought against witches was that instead of attending church and being solemn and serious, they were out partying, whether with each other, the devil, with fairies or the Wild Hunt. Among the crimes associated with witchcraft was having fun at a time when fun was suspect. What exactly were those witches accused of doing at their sabbats? Feasting, dancing, making love. So-called telltale signs of witchcraft are those stereotypes that automatically brand a woman as a witch: among the most common is loud, hearty laughter—the infamous witches’ cackle.

Читать дальше

It is no accident that the element universally associated with witchcraft is water, whose tides are ruled by the moon; water appears, disappears, changes shape, shifts continually, but remains rhythmically constant

It is no accident that the element universally associated with witchcraft is water, whose tides are ruled by the moon; water appears, disappears, changes shape, shifts continually, but remains rhythmically constant