Within months of the London opening, there were productions across the country – Edinburgh, Oxford, Liverpool, Ipswich, Dublin and Belfast newspapers all carried advertisements, although only the Hampshire Telegraph mentioned the novel staging, the original selling point. Instead, many theatres interpolated local speciality acts. In Portsmouth, audiences were promised ‘a Parody on the popular Song of “The Sea, the Sea, the open Sea”,’ as well as the appearance of Miss Parker to sing ‘A Kind Old Man Came Wooing’.

By 1839, the novelty staging was used in other plays. A production of Jack Sheppard at Sadler’s Wells had a similar compartment set to show Sheppard’s escape from Newgate: ‘Four Cells, two above and two below … doors, leading from one cell to the other – a fire-place at the back’. As the audience watches, Sheppard frees himself from his fetters, scrapes away at the brickwork until he can wrench out the bar blocking the chimney flue, which he then climbs into and vanishes from sight. In a moment, a hole opens in the cell above, and Sheppard appears once more. He then breaks down the cell door and vanishes through it, to reappear above, on the flat roof of the prison. This was very obviously of enormous drama, for at that moment, instead of escaping, Sheppard says, ‘Ah! my blanket! I had forgotten it,’ and makes the entire trip in reverse: through the two cells, down the hole in the chimney and back into the condemned cell. He collects his blanket, and the audience watches as he makes the trip a third time. On the roof he then tears up the blanket and is finally seen through the cell window abseiling down the side of the gaol.

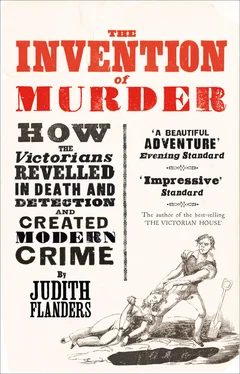

Given Fitzball’s triumphant success, it is a surprise to see almost no subsequent fiction based on Bradford’s story. The only adaptations of any repute are three versions all by Sheridan Le Fanu, the Irish novelist and ghost-story writer. *He approached it first in 1848, in ‘Some Account of the Latter Days of the Hon. Richard Marston’, then again three years later in The Evil Guest. A third version, A Lost Name, appeared in 1868. All were variants on the same story: a man of bad character is found dead at a friend’s house. A faithful servant is suspected (and in one of these versions confesses), but it was the friend who killed him, after which the servant came into the room to find him dead, as in Bradford. When a memory of the penny-blood version cropped up in Dickens’ ‘The Holly Tree Inn’ (1855), it was as ‘a sixpenny book with a folding plate, representing in a central compartment of oval form the portrait of Jonathan Bradford, and in four corner compartments four incidents of the tragedy’. What had lingered in Dickens’ memory was the staging.

Instead, it was the penny publications that picked up the story, following the stage version closely, rather than inventing facts or characters to beef up the eighteenth-century story on their own. The real crime had by now been almost entirely forgotten. In the 1850s, in publishers’ lists of penny-bloods, Jonathan Bradford appeared together with fictional titles like The Poisoner, or, The Perils of Matrimony. Jonathan Bradford, or, The Murder at the Road-side Inn. A Romance of Thrilling Interest was published in eighteen parts, attributed to ‘the author of “The Hebrew Maiden”, “The Wife’s Secret”, &c. &c.’, who is thought to be Thomas Peckett Prest, a prolific penny-writer who had had a hand in the original version of Sweeney Todd . This was very much a story aimed at the working classes, in that throughout it is the petty bourgeoisie who thwart the good honest working people. An unpleasant, officious lawyer casts suspicion on all the good characters, while Dan Macraisy, the highwayman, although condemned in somewhat perfunctory fashion for being a murderer, offers the justification that ‘perhaps if this Mr. Hayes had not gone about with so much gold in his pocket, he might have been alive at this moment’. It was the victim’s fault for being rich while others were poor.

And finally, Jonathan Bradford cropped up regularly in police reports when penny-gaffs were raided, or booth-theatre proprietors were prosecuted for performing without a licence. Household Words also published a reminiscence of childhood ½d. peepshows, describing a showman who carried a box on his back. ‘The interior was lighted up with a candle in the middle of the day, and the different highly-coloured tableaux were let down with a heavy flop by strings at the side. wonderful atmospheric effects were introduced at the back, by lifting a lid, and the whole was made more interesting by a running description. by the proprietor.’ The shows that were mentioned by title were Mazeppa (Astley’s most popular hippo–drama) and Jonathan Bradford.

The most lasting, and most important, contribution of the Jonathan Bradford story was to extend our ways of seeing. In 1852, the playwright Dion Boucicault adapted a French play as The Corsican Brothers. Originally it had been a very ordinary melodrama of a murdered man and his brother’s revenge. Two elements, both descendants of Fitzball’s Jonathan Bradford, lifted the piece out of basic genre and made audiences see anew. Acts I and II of the play were to be understood to occur simultaneously, seen from the perspective of each brother; furthermore, at the end of Act I, the actions that would take place at the climax of Act II were, with the aid of new stage technology, played out at the back of the stage as a ghostly pre-vision.

In 1858 the idea of simultaneity of view was taken further by the painter Augustus Egg. His Past and Present triptych is a morality tale, set, like a theatrical melodrama, in a middle-class home. And, like Jonathan Bradford, it shows in its tripartite structure actions that take place in different – and simultaneous – times. The centre panel shows the moment a wife’s adulterous liaison has been discovered by her husband. Egg’s depiction could be a tableau from any melodrama, with the husband holding the telltale letter, the woman in a swoon at his feet. (Over his shoulder is a painting of a shipwreck by Clarkson Stanfield, a noted set designer, tying the story even more tightly to the theatre.) It is the outer wings of the triptych, however, that make the work so innovative. Both are set some time after the central scene. On the left, the adulterous woman, reduced to destitution, sits under the arches by the river, contemplating suicide as she gazes at the moon. On the right, her two soon-to-be-motherless children are alone in their attic room, also staring at the moon, which is covered with the identical cloud formation that the mother is staring at, indicating that the two panels are depicting the identical moment in time. As both the children and their mother face inwards, to the central panel, Egg also conveys that they are, simultaneously, all thinking of that day when their world collapsed.

By 1871, The Book of Remarkable Trials gave only one page to Bradford (Jack Sheppard had twenty, Eugene Aram seventeen), and the author excused the scanty coverage: ‘The details of this case reach us in a very abridged form; and we have been unable to collect any information on which any reliance can be placed.’ The next murderer, John Scanlan, was even more completely subsumed into his dramatic doppelganger.

Dion Boucicault had had a huge success with The Corsican Brothers in 1852, that play of double identities and duels, revenge and apparitions, with a famous double role for the actor-manager Charles Kean. But the two men quarrelled, and Boucicault and his actress wife went to New York, where in 1860 he wrote and they both starred in The Colleen Bawn. In triumph, they returned to London, to produce an amazing ten-month run of the play at the Adelphi Theatre.

Читать дальше