1 ...6 7 8 10 11 12 ...15 For want of a better model, early tactics at sea had followed the orthodoxies of land battle. The Spanish in particular took on board a military mentality based on strict rank, fortresses and close combat. They built ships with ever more elaborate upperworks. Soldiers would assemble for attack high in the floating arcades while sailors, with the status of water-carriers, performed their strange business with canvas and cordage. European kings were slow to see the strategic value of smaller, free-ranging fleets, preferring the ships they built to reflect their own magnificence. The Swedish king built the 230-foot Elefant. James IV of Scotland went one foot bigger with the Great Michael, which encouraged Henry VIII to join in and build the Henry Grace à Dieu. When he sailed to meet Francis I at the Field of the Cloth of Gold, the gilded sails glowed like the morning sky. Francis I himself took royal hubris further with the Grand François: a crew of 2,000, an onboard windmill, tennis court and chapel. Before even reaching the open sea, the Grand François was wrecked.

The success of English ships from the 1570s onwards stemmed in large part from leaving behind land-based hierarchies and abiding by the laws of the sea. Ventures were plotted in small harbours, in shoreside manors like Arwenack, not in court. Ships were self-contained, small-scale units of enterprise and power, and in Elizabethan England their design developed accordingly, producing compact and agile craft. Far from shore, and in the capricious hands of wind and waves, the spirit on board was more egalitarian than anywhere on land. ‘I must have the gentleman to haul and draw with the mariner,’ declared Drake on his circumnavigation, having just executed the troublesome courtier Doughty.

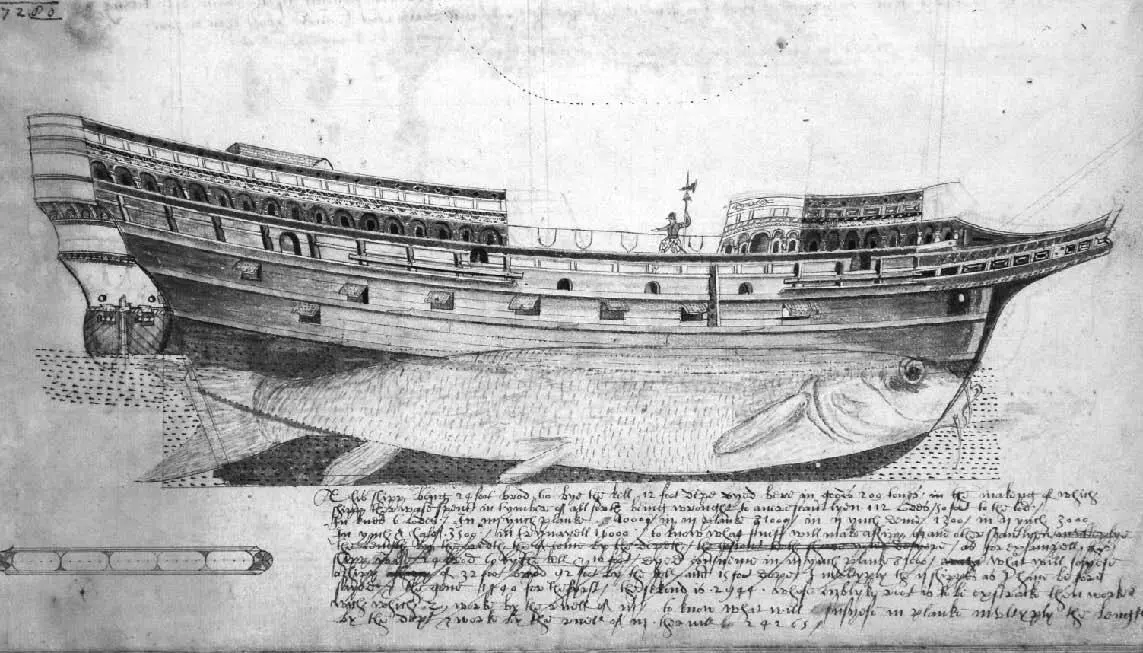

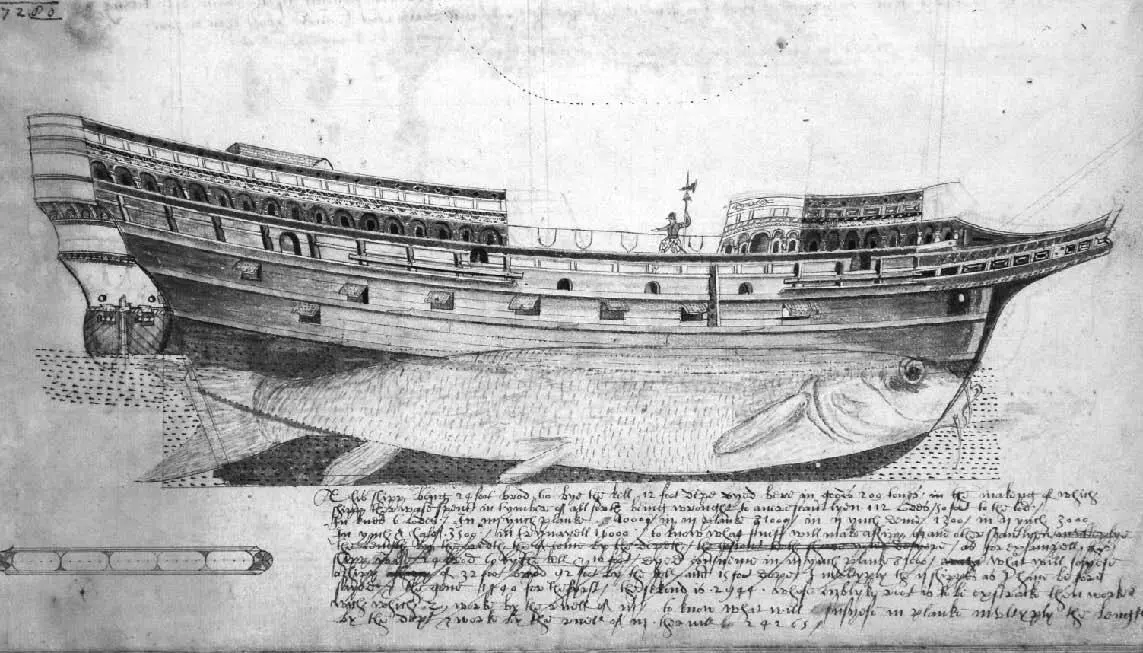

Even now, though, it is hard to glean very much about sixteenth-century ship design. The preserved boards of the Mary Rose are among the few actual relics. Otherwise there are only chance images – tapestries in Portugal, paintings in the Alhambra, the seal of Louis de Bourbon, Henry VI’s psalter, chest designs, or manuscripts like that of Anthony Anthony or Burghley’s folio of Falmouth Haven. From these sources, a vague outline of development can be traced. Masts grow in number along the deck, yards sprout from them. A bow-rigged flagstaff in one period has mutated into a spritsail in the next. Sometimes a ship will be shown with an experimental spar, which then disappears like some redundant limb. Rarely has the growth of a technology so closely mirrored biological evolution.

The vessels themselves have long since vanished, wrecked or destroyed by fire, or after countless gravings and rebuildings and re-riggings, the cutting down of decks, stripped of all blocks and fittings, then taken up some muddy creek to settle slowly back to nature, their timbers broken down by the drilling shell of shipworms. Like some race of aquatic dinosaurs, Tudor ships have been reassembled from the faintest of traces. But in the Pepys Library at Magdalene College, Cambridge is a set of papers that gives the only detailed glimpse of the process and thinking behind their construction, and of this decisive moment in man’s relationship with the sea.

Storm-clouds press down dark and close above the Fens. I scuttle across Magdalene’s quads just as the first patter of rain rises to a crescendo. It is the day after seeing the Burghley Map, and now in the upper room of the Pepys Library, with the same thrill of expectation, and to the sound of approaching thunder, I lay out another ancient volume, between another pair of pasteboard covers.

When he died, Samuel Pepys left a collection of some 3,000 books. Among the large number concerning maritime history was a series of loose folios which he had bound into a volume, naming it Fragments of Ancient English Shipwrightry. They include the country’s earliest record of paper plans for building ships. Looking at them, you can sense the process of experimentation, with the dividers’ prick-marks still visible, and the arcane grids of hull curves framed with marginal calculations. Other folios place the art of shipbuilding in a much wider context. Included by Pepys is a painted image of Noah’s Ark – ‘Noah did according unto all that God commanded him even so did he make thee an arke of pine trees …’ Another page has jottings about Jason’s voyage to Colchis, and the invention of ships in the Hellespont. The overall impression is less of an inquiry into a practical problem than a quest to rediscover some lost secret – closer to the spirit of the Renaissance than the Enlightenment.

The papers are attributed to Matthew Baker, greatest of Elizabethan shipwrights. Baker was the first to leave a record of the abstraction of hull design into numerical proportions, the first to have a ship built from his blueprints (the private warship Galleon). It was he who built the Revenge, Drake’s flagship in 1588, from whose decks Grenville later fought the most famous rearguard action in English history. Martin Frobisher’s three Baffin Island expeditions used Baker’s ships. In his Seaman’s Secrets John Davis said that as a shipwright Baker ‘hath not in any nation his equall’. To many of his contemporaries, Baker’s craft put him on a par with Vitruvius and Dürer.

Among his bound papers in the Pepys Library is what is believed to be a self-portrait. Baker is shown standing at his plan table which is spread with instruments of drawing and mensuration. He holds a pair of dividers and is marching them over the drawing of a hull. The dividers are exaggerated, some three feet high, and there is something faintly comic about the image. Though Baker’s head is bent in earnest concentration, his left leg is kicked up behind him, giving the impression that he is skipping as he works.

It is Baker who is credited with the design that revolutionised English shipping. Rejecting the cumbersome, castellated upperworks that compromised ships’ seaworthiness, he helped develop a much lower, sleeker form, recognisable in the shapes of those on the Burghley Map lying off Arwenack Manor. Initial resistance to the new hull shape came, it seems, from Queen Elizabeth and Lord Burghley (as well as possibly from John Hawkins, the Navy’s treasurer to whom, paradoxically, Baker’s innovation is often attributed). Baker had a battle to fight in gaining approval for his revolutionary design, a battle that produced the most unusual image in his collection.

Baker has used a fish. He has transposed the profile of an Atlantic cod below the waterline of his ship. The curve of the fish’s belly gives the distinctive ‘crescent’ shape to the keel. The long upward slope towards the tail represents the pinching of the floor that produces the sharp and narrow after-keel section. (The convention of good ship design was long framed in the expression ‘cod’s head and mackerel tail’, which persisted for yachts right up to the 1960s, when the convention was suddenly reversed, the sleek tail in the bows, and the bulk of the beam aft.)

Baker’s cod is not an exact fit, the cod’s distinctive fat lips stick through the stem while the flukes of the tail do not correspond to very much. But that makes its use more interesting. Clearly, the cod was persuasive.

From Fragments of Ancient English Shipwrightry.

Such animism has always been a part of seafaring. So much is unknown, so much goes on unseen beneath the surface, and such are the uncertainties and risks of being on the water that pure reason rarely survives very far from the shore. A certain imitative instinct is in the name of the high-bowed West Country boat, the balinger (balaena – Latin for ‘whale’). Likewise, the forces of the sea should be absorbed rather than resisted. It was believed that a ship that flexed with the water was a good one, and there were instances of pirates who removed some of the ship’s frames to make it even more flexible. Whatever the exact thinking behind Baker’s cod, it represented an alternative to building ships like castles, a recognition that the best way to prosper away from land was not by transposing terrestrial forms but by realising that the sea operates by its own set of rules.

Читать дальше